Education is highly correlated with a range of socio-economic outcomes, not least earnings and employment. These types of correlations might reflect pre-existing relationships between socio-economic outcomes and family background – i.e. that wealthier, more well-connected children obtain education, skewing the relationship between education and earnings. However, there is now abundant evidence that education pays off across the socio-economic spectrum.

As a result, closing the distance between the levels of educational attainment of those in the richest and poorest households – “attainment gaps” – has been a central theme in the manifestos of all major parties’ in past elections. We expect this election to be no different.

Policy in the last parliament

The existence of such gaps prompted the current Scottish Government to establish a £750 million Attainment Scotland Fund in 2015 which has been used to achieve the goals set out in the Scottish Attainment Challenge, National Performance Framework, and National Improvement Framework.

Since 2015, the Attainment Scotland Fund has been used for three main purposes:

- establishing the Pupil Equity Fund providing direct financial support to schools which headteachers can use at their discretion to fund projects;

- setting up the Challenge Authority and Schools Programme to provide additional funding and support for local authorities and schools experiencing the most severe levels of deprivation; and

- providing additional support through the Care Experience Children and Young People initiative for children who have spent time social care.

These strands of funding have aimed both to provide resources to those working directly with children from deprived areas, as well as to establish processes through which long-term progress could be made. So far there have been three evaluations of the Fund (the latest published in October 2020), and although they have found its coverage has been wide and that many headteachers report positive impacts, there has not been a “consistent pattern of improvement” in quantitative measures of the attainment gap.[1]

An Audit Scotland report, published in late March, expressed similar findings in their evaluation of “how effectively the Scottish Government, councils and their partners were improving outcomes for young people through school education”. The report notes that although there has been progress in closing attainment gaps in the last decade, it has not been broad based across measures, or regions of Scotland.

What drives attainment gaps?

There are two general forces at play in determining attainment gaps. First, there is the education system and the role of its infrastructure. For example, the quality of school buildings, the core curriculum, and the training of teachers and staff. Education is a devolved policy area, and so can be directly influenced by the Scottish Government.

Second, there are wider socioeconomic forces that mean, even if these institutions were “perfect”, gaps in attainment would persist. For example, lower-income families might face tighter time and financial constraints that limit their ability to provide educational and recreational childcare. These forces are difficult to pin down, and as a result are more difficult to target through policy.

In this briefing we focus on educational attainment gaps in Scotland. These are broadly measured by taking the difference in the proportion of children from the least and most deprived areas reaching certain educational milestones or obtaining particular qualifications. The “least deprived” and “most deprived” areas are defined according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). The SIMD is typically used in analysis of national attainment gaps since it can act as an up-to-date, albeit imperfect, proxy for household income for the entire population of pupils in Scotland. Using SIMD as this type of proxy assumes socio-economic background is well approximated by geographical location. This is perhaps somewhat unrealistic since there is often substantial variability in measures like household income within regions, and is particularly problematic in rural areas where the size of data zones are large.

Although, the SIMD data zones are disaggregated to an extremely low-level, the data from which the statistics we analyse here are derived come from Schools, which often serve several of these low-level data zones. Using information on actual household income of children would provide a more detailed – and more likely than not more pessimistic – picture of the extent to which family background is correlated with attainment, however this information is not currently available at the required frequency and scale.

It is also important to note that it is not possible to separately identify the contribution of either the education system or wider socio-economic factors in generating attainment gaps by comparing attainment levels in this way. However, both almost surely play their part.

Attainment gaps over the last decade

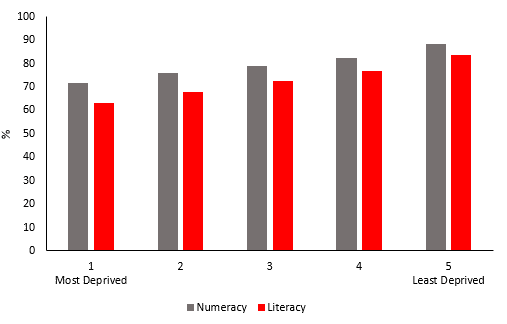

In Scotland, children who live in the most affluent areas are considerably more likely to reach the expected levels of numeracy and literacy for their age across various years of primary school. Chart 1 shows that 88% and 84% respectively of those in the most affluent areas of Scotland achieve the expected level in numeracy and literacy across Primaries 1, 4, and 7. In contrast, the proportion of those in the least affluent areas who achieve the same is considerably lower (only 72% and 63% respectively).

These gaps have declined slightly over time, more so in the case of literacy, however not to the extent that there is anything close to parity between the groups. Levels of numeracy and literacy by the end of primary school determine how children engage with the senior Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) in the first two years of high school, and subsequently how they are assigned to classes as they begin their preparation for their National exams – the exams that determine whether or not they can advance to taking Higher and eventually Advanced Higher exams.

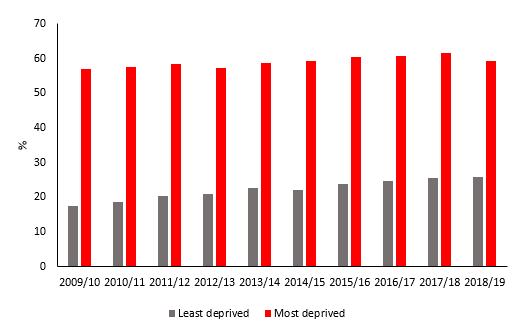

Later down the educational pipeline, fewer high school leavers from the most deprived areas obtain these qualifications – those which are necessary for continuation into higher education. Chart 2 shows the percentage point gap between the percent of high school leavers in the most and least deprived areas who obtain at least one SCQF level 6 (higher equivalent, red line) and SCQF level 7 (advanced higher equivalent, black line) qualifications over between 2009/10 and 2018/19.

Chart 1 – Percent of children in primaries 1, 4, and 7 achieving the expected numeracy and literacy levels by SIMD quintile.

Source: Scottish Government

There has been some progress towards closing the gaps in high school attainment. The difference in the proportion of children achieving at least one SCQF level 6 qualification declined by almost 10 percentage points between 2009/10 and 2018/19. However, there was still a large difference in the proportion of the two groups achieving this level of attainment (35.8 percentage points). The gap in level 7 attainment has been stubbornly high over the same period, seeing next-to-no decline with the attainment rate among those in the least deprived areas being consistently between three and a half to four times as high as among those in the most deprived areas.

Again, it is these SCQF level 6 and 7 exams that determine whether or not young adults can apply to university. Typically, the threshold for doing so is obtaining at least passes in five Higher examinations, SCQF level 6 equivalents.

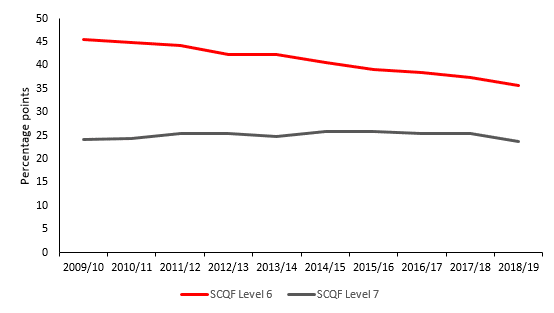

It is unsurprising then that a far higher proportion of school leavers from the most affluent areas enter higher education. Chart 3 shows the proportion from both the least and most affluent areas in Scotland who continued on to higher education from 2009/10 to 2018/19. The grey bars in Chart 3 show that proportion of those in the most deprived areas doing so has increased to roughly one-quarter over the period; again, a sign of progress in closing attainment gaps over the past decade.

Chart 2 – percentage point attainment gap for SCQF level 6 and 7 qualifications between the top and bottom SIMD quintiles, 2009/10-2018/19

However, over the same period consistently around 60% of those in the highest SIMD quintile left high school and went on to higher education. As a result, in 2018/19 the proportion of students in the most deprived areas moving on to higher education (upon leaving high-school) was less than half the proportion of those in the least-deprived areas doing so.

The latest attainment data and the potential effect of Covid-19

Although inequality in attainment is still apparent in Scotland Charts 1-3 show progress has been made over the past decade in closing some of Scotland’s education disparities – a point noted in both the latest evaluation of the Attainment Fund and Audit Scotland’s recent report. Given the mass-disruption to schooling in the last year, however, it remains to be seen whether there might be some backward steps in this regard in the years to come.

In February of this year, the Scottish Government released high school attainment statistics for the year 2019/20. They suggest that the pandemic has acted only marginally – for this cohort – affected the attainment gap in SCQF level 6 qualifications. There was a larger increase (4 percentage points) in the SCQF level 7 attainment gap relative 2018/19. Looking beyond this headline figure, however, the increase wasn’t a story of attainment among those in the most deprived areas falling. In fact, the rate of attainment increased by almost half (from 8.7% to 11.7%). The gap only increased because of an uplift in this level of attainment among those in the least deprived areas that was over two and a half times as large – up 7.1 percentage points from 32.4% to 39.5%.

As this these large increases suggest, these statistics are have been affected by the large-scale shock to the education system that occurred during the second half of the school year they cover. As a result, we cannot draw any clear conclusions from them in terms of longer-term trends in the attainment gap, or the potential future effects of the pandemic. For this, we will have to track the achievement and attainment of future cohorts.

Chart 3 – percent of Scottish high-school leavers going to higher education in the top and bottom SIMD quintiles over time

Note: includes leavers across s4, s5 and s6. Source: Scottish Government

There is emerging evidence that children in low income families are less likely to get academic and emotional support than their high-income counterparts. For children in the latter years of high school, this could have and immediate knock-on effects on their attainment (in the form of exam results) in the coming year(s). In the wake of the release of last year’s s4-s6 exam results it became clear that initially children from disadvantaged backgrounds were disproportionately “downgraded” as a result of the algorithm used to predict grades. Although only Higher exams will be taken this year, and the Scottish Government have committed to using teacher predications/evaluations as opposed to algorithms, the extent to which the loss of teaching time has had an unequal impact in this regard remains to be seen.

From a longer-term perspective, the loss in school time could also widen gaps in basic skills – for example in numeracy and literacy – among children in primary school. Whether these close of widen over time and have knock-on effects on attainment in years to come is also an open question.

As a result, it could well be the case that the pandemic and lockdown will have acted to reverse some of the trends of the past decade, even if only in the short-term.

Conclusion

There is both a current and historical socioeconomic gap in educational attainment in Scotland. In 2018/19 (the most recent data), the proportion of children in most affluent areas leaving school for higher education was 33.4 percentage points higher than among those in the least affluent areas. This is in spite of progress in reducing attainment gaps over the past decade.

These gaps have had a central position in political discussions of inequality over the same period. As a result, it is likely that the difference in educational outcomes across deprivation levels will garner attention in the upcoming election. Look out for policies both directly aimed at changes to the education system, as well as those wrapped in the terminology of “social mobility” or “equality of opportunity”.

This would most likely have been true even in the absence of the now year-long disruption to education that has resulted from the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the evidence that this might have acted to widen educational inequalities, it is likely that inequality in attainment and policies to offset the effect of the pandemic might be even more prominent in over the coming months.

Endnotes

[1] See E9, E13, E17, and E18 of the Executive Summary in the latest evaluation report.

Authors

Mark Mitchell

Mark Mitchell is a former research associate at the FAI. In 2021, Mark moved to a post in the Competition and Markets Authority. His research area is applied labour economics, focussing on the causes and effects of human capital accumulation over the lifecourse.