On the 3rd of August 2021 the Scottish Government announced the end of most COVID-19 restrictions in Scotland. Whilst this is great news for tourism industries in the economy it is still important to understand the impact that the pandemic has had and will have on our economy. In a previous blog we have discussed how we intend to use a large scale multisectoral economic model to capture some of these impacts. This blog sets out the quantitative scenarios that we have developed in the first six months of our project, and that are used to inform our model.

2021 so far and beyond

So far, 2021 has been characterised by different degrees of public health measures in place, including restrictions on travel and social and economic activities. These have varied by month and by local authority. For instance, the first quarter of the year has been characterised by the presence of a “stay at home” type of restriction and the development and roll-out of a large-scale vaccination programme. This was followed by move to a tier system that classified areas based on infection rates, which saw a loosening of restrictions – including travel permitted – in and to areas.

Looking ahead, the Scottish and UK Governments have set out their roadmap to relax restrictions in the coming weeks and months. It is clear that loosening and removing such restrictions is having and will have a significant impact on the tourism industries in Scotland via the so called “demand-side” channels. Indeed, the return of domestic trips, “staycations” and possibilities of overseas travel has been widely discussed in the media. However, COVID-19 has also so called “supply-side” impacts on businesses. For instance, sickness, absenteeism or self-isolation of workers impacts the capacity of tourism businesses to operate or constitutes additional costs. We are watching both channels carefully to see if there is any evidence, for instance, that isolation requirements limit the ability of tourism operations to meet likely demand.

Quantitative demand-side scenario

To perform our analysis, we first need to estimate a baseline against which scenarios can be compared. Essentially we attempt to estimate an alternative 2021 without COVID-19. For this, we have used secondary data from a wide range of sources to create a disaggregated picture of the levels and pattern of spending by tourist category across Scotland in the years before the pandemic. This considers three dimensions of tourism spending in Scotland:

1) the origin by place of residence (both domestic – Scotland, outside Scotland but in the UK and international (I.e. non-UK);

2) the destination by location of spending (i.e. Scottish local authority);

3) spending by month and by economic sector (for instance, overnight tourism spending includes an element for accommodation, which is not there for day trip visitors).

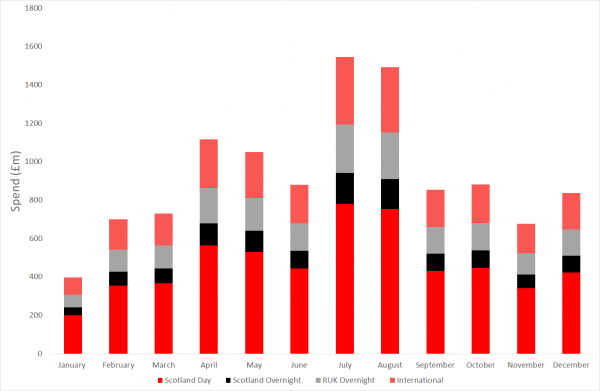

Total Scottish tourism demand for 2021 is obtained by adding international and domestic and day trips tourism. Overall, we estimate that this amounts to £11.62 billion. Figure 1 gives a monthly breakdown.

Figure 1. Monthly breakdown of tourism spend in the baseline, £m

Source: Author’s calculation

Counterfactual scenario and restriction levels

Our counterfactual scenario for 2021 is based on travel and other restrictions that have been in place since the beginning of January and on projections of restrictions for the rest of 2021.

We use these Tiers system introduced by the Scottish Government as the main driver for tourism demand for day and domestic overnight tourism due to the limitations of capacity and travel. (We treat international tourism in Scotland differently, and set out why below.)

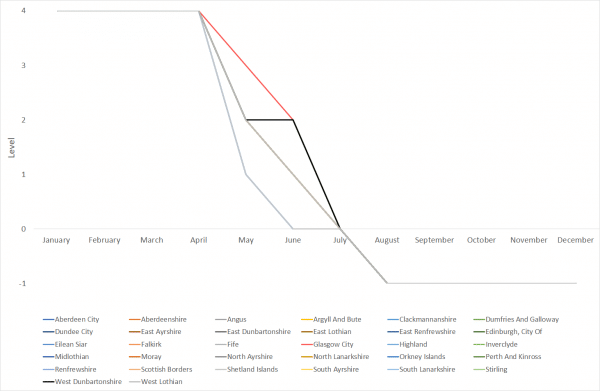

When we set the Tier level for each of the 32 local authorities by month (Figure 2), these are combined with further assumptions about the link between Tier level and the level of tourism spending relative to pre-COVID levels, which are informed by discussion with stakeholders and information of available surveys and other information (Table 1). This produces an estimate for the change in domestic day and overnight tourism by month and local authority.

Figure 2. COVID levels by local authority by month

Table 1. Spending assumptions for COVID restriction levels

| Local Authority COIVID level | Spending assumptions |

| Level 4 | 0% |

| Level 3 | 30% |

| Level 2 | 50% |

| Level 1 | 70% |

| Level 0 | 90% |

| Level -1 | 100% |

International travel is treated differently as the level of tourism demand is driven mainly by border travel restrictions in place both in the country of origin and of destination. At time of writing, the UK operates a three-tier system whereby arrivals to the UK are classified by the country of departure to one of “green”, “amber” or “led” lists. Currently, travellers from countries on the “green” list countries have quarantine free travel to the UK. Travellers from “amber” countries needed to quarantine for 10 days until the 19th of July, and now have rules comparably similar to “green” list countries in the majority of cases, while only British nationals and residents are allowed to travel from red list countries and again need to quarantine in designated hotels. In our modelling, using World Tourism Organisations and Visit Britain data, we estimate that spend in international travel for Scotland will reduce by 93% on pre-pandemic levels in the first seven months of 2021 and will recover slightly over the rest of the year.

Combining the domestic day and overnight scenarios with international case, we currently estimate that Scotland will see a £5.5 billion (49.3%) reduction in tourism spend in 2021 compared to our estimated baseline. This will constitute an additional demand-side shock to our economic model, which will capture the knock-on impacts of this across all sectors and across the geography of Scotland.

Unknown elements of demand

One key unknown of Scottish tourism demand is if, in addition to the travel restrictions impact on tourism arrivals, these also prevent or limit travel departures from Scotland, causing a substitution effect of foreign for domestic tourism trips by Scottish residents. Any increase of domestic tourism could somewhat negate the impact of the reduction in international tourists spending in Scotland. From Scottish Government data we know that in 2017 (the model calibration year) Scottish residents spent £2.4 billion outside of Scotland. We will consider some retention in Scotland of spending which would in a normal year take place abroad in a further simulation.

Quantitative supply-side scenario

In addition to the reduction in tourism demand, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the supply-side, in particular on the labour market and labour supply. As a result, when workers self-isolate, they are unable to attend their workplace, and the supply of labour falls. Regulations state that any individuals who test positive for COVID must self-isolate for a further ten days. Furthermore, anyone identified as a “close contact” must isolate for 10 days from the test date. This has been commonly known in the media as the “pingdemic”. This has an impact on labour supply in particular were case numbers – and identified close contacts of positive cases – to rise at the same time as relaxations on remote working and reductions in the scale of the furlough scheme act to encourage workers to return to physical (non-remote) places of work. Tourism-facing industries mostly involve jobs that cannot be completed from home.

To estimate the change in labour supply we use the Scottish Business impact of COVID-19 Survey (BICS). BICS is a voluntary fortnightly business survey used to gauge the impact COVID-19 has had on financial performance, workforce, prices, trade and business resilience. Using the Wave 18-32 we are able to estimate the reduction in labour supply in tourism sectors of 1%. Unfortunately due to sensitivity issues the BICS self-isolation data is only available at an aggregate level, which we use as a proxy for tourism industries.

Our modelling approach assumes that the reduction of labour supply caused by self-isolation impacts upon the sectoral price of labour. For the tourism sector, which mostly requires on premising working, if a member of staff is self-isolating then another member of staff would be required to cover, which is essentially an additional cost. When this is not possible, the business becomes less productive as less labour input is available. For our simulation we estimate the price change using the change in labour supply (1%) along with the base year productivity (output per FTE) for each of the tourism sectors.

Conclusion

All in, the framework set out in our earlier blog provides a useful way for analysing the whole economy impacts of changes in the tourism economy coming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

We have set out how our project has developed a detailed disaggregation of tourism spending which permits the generation of demand scenarios linking to Tier levels at the local authority detail and construct hypothetical projections for tourism spending over 2021. On the supply-side, firms productivity is being negatively impacted by labour availability which will likely impact business activity both in the short-run – an inability to meet demand given staff isolating – and in the long-run, as firms require to train new staff with appropriate skills.

Case numbers, enacted and proposed policy responses, as well as behavioural and psychological responses of individuals to the changing pandemic are changing every day it seems. In our next blog, we will set out our simulation results, which will have two uses: first, these will establish the possible scale of the challenge to the tourism industry through 2021, when there is still time in the year to develop responses to the current challenges. Second, it can provide a useful benchmark for the responses from all actors in the industry to ensure that the actions required to recover from the pandemic are centred in the minds of all who lead this critical economic sector.

Authors

Grant Allan is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economics. Grant has research interests in applied regional economic analysis and modelling, particularly in the areas of energy and tourism.

Kevin is a Chancellor's Fellow in the Department of Economic with a focus on the use of regional economic models for policy analysis. Areas of interest include; energy and climate change, poverty and tourism.

Gioele is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economics, University of Strathclyde.

-768x432.jpg)