This week is Challenge Poverty Week in Scotland, an annual programme of events that bring together many people, politicians and organisations to talk about poverty and how to solve it.

So what is poverty, why does it matter, and what are we doing about it? Here are some key poverty facts to give you the lowdown on what you need to know.

What is poverty?

Many people have their own slightly different view on what poverty is, but here we quote directly from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) who are one of the longest established charity that campaigns on poverty in the UK:

“Poverty means not being able to heat your home, pay your rent, or buy the essentials for your children. It means waking up every day facing insecurity, uncertainty, and impossible decisions about money. It means facing marginalisation – and even discrimination – because of your financial circumstances. The constant stress it causes can lead to problems that deprive people of the chance to play a full part in society. “ https://www.jrf.org.uk/our-work/what-is-poverty

How is poverty measured?

This is an even more difficult question, and as yet no one has come up with a universally agreed robust measure that captures everything. What most people use is the measure of relative income poverty which defines a person in poverty if they live in a household with income below 60% of median income. This relative income measure means that we view poverty in the light of resources available to wider society.

It is not a perfect measure, for instance if a household has a lot of savings but low income, they would be captured in the relative income poverty measure but unlikely to be facing the reality captured in the JRF definition above. There have been some attempts to improve the relative poverty measure – see the Social Metrics Commission as an example.

Most of those who research poverty insist that more than one measure of poverty is needed to understand the true picture – for example looking also at the ability to afford basic goods and services.

How many people in Scotland are in poverty?

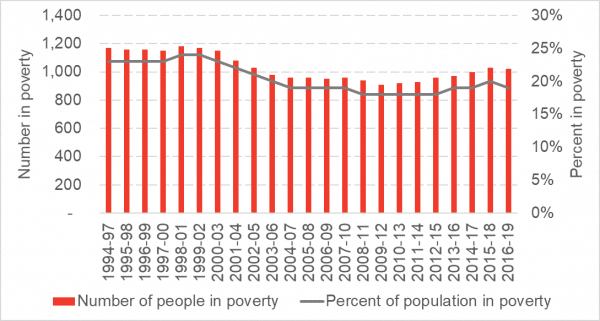

The Scottish Government provides an excellent annual statistical summary of different poverty measures in Scotland. Most headline measures of poverty use an after-housing cost measure to capture the large and unavoidable cost of housing which impacts significantly on the amount of income people have to live on. Because the measures rely on survey data (mostly the Family Resources Survey), and the sample for Scotland is relatively small, the Scottish Government usually use a three-year moving average to measure poverty changes over time.

In the most data, 2016 – 2019, 1.02 million people in Scotland (19% of the population) were living in relative poverty after housing costs. The proportion of people in poverty fell during the early 2000s reaching its lowest point in 2009-12. Since then it has risen slightly but appeared to fall marginally in the most recent set of published data (this is pre-coronavirus).

Chart: Relative (After Housing Cost) Income Poverty in Scotland

Source: Scottish Government

What causes income poverty?

There are three main determinants of relative poverty.

- The first is the amount of income that comes into the household via employment. Clearly, if no one in the household is working, it is much more likely that a household will be in poverty. However, half of all people in poverty live in a household where someone works.

- The second determinant is how much money is coming in via social security income. This is an important component of income, particularly for those who have barriers to working full-time such as those with disabilities and lone-parents.

- The third is the amount of money spent on housing costs, with rent the largest cost that most families in poverty face. Poverty is lower on a before housing cost measure which means that it is housing costs, not their underlying income, that is the reason they are in poverty.

Even short periods of living in poverty can have life long implications. For example, lower educational attainment and child poverty go hand in hand. Long term impacts on health are also well known – and we have seen the fatal ramifications of this in more deprived communities during the pandemic. Long term health issues and poorer educational attainment affect society and the economy, as well as individuals and their families.

What is the Scottish Government trying to do to tackle poverty?

Tackling poverty is one of the National Outcomes prioritised in the National Performance Framework. Most action is focussed on child poverty following the passing of the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 which commits the government to reaching ambitious targets on child poverty. The targets are based on four measures summarised in this Scottish Government infographic. The relative poverty target is for only 10% of children to be in relative poverty by 2030/31, with an interim target of 18% in 2023/24. The rate in 2018/19 was 23%.

What progress was being made?

Pre-pandemic, whilst child poverty did not appear to be worsening, nor was it getting significantly better. Many parts of a Scottish Government 2018 plan to tackle child poverty are either in place, or soon to be enacted, and it may be too soon to see these impacts in the headline statistics.

However, there is concern that the Scottish Government are not doing enough to meet their own imposed targets. In truth, no one actually knows if this is the case as there isn’t yet the capability to predict or measure the impact of many of the policies in the 2018 delivery plan.

A previous article discussed this further, and emphasised the importance of evidence-based and regularly monitored policy on child poverty in order to ensure that enough progress is being made.

The next delivery plan is due in spring 2022, and the outlook by then will be further complicated by the fallout from the pandemic. Ensuring that analytical tools are able to provide information on likely scale of the impact of policy, with follow up evaluation to understand what did and didn’t work, will be really important. Otherwise, the worry is that the government will fall far short of its ambitions without even knowing why.

What impact will the pandemic have on poverty?

Data on poverty is released with long lags, so it will be a couple of years before we know exactly what has happened to incomes. Clearly, the turmoil in the labour market will have had significant impacts on some people’s incomes – and not just those already on low incomes.

We’ve had more support provided through the social security system with a £20 a week uplift in the Universal Credit standard allowance. This is quite a significant sum of money for those at the lowest end of the income distribution and could actually have pulled some people out of poverty (although not all social security claimants on some of the older out-of-work benefits were able to get it).

Overall, there will have been a lot of churn in the income distribution and it’s not over yet. But if we look at the JRF definition at the start of this article, it’s probable that more people have found themselves in the situation described. Food bank usage is one indicator of that: according to the Independent Food Aid Network (IFAN) there was a 113% increase in emergency food parcel distribution between February and July 2020.

What will the next year bring?

As with everything right now, there is a lot of uncertainty about what will happen in the next 12 months. With the end of the pandemic still not in sight, it seems likely that things will get worse before they get better. The scaling back of government support, for example from the job retention scheme, means that is likely that more people will be faced with cuts in their income. The £20 a week increase in the Universal Credit standard allowance is also due to be phased out in April 2021.

On a brighter note, the Scottish Government’s delayed Scottish Child Payment is due to start paying out an additional £10 a week to low income families with children under 6 in February 2021 as part of their efforts to make progress towards the child poverty targets. However, even the Scottish Government admit that much more needs to be done. Expect child poverty to be a key topic in next year’s election.

Putting effort and resources into effectively tackling poverty will provide direct benefits to many people in Scotland, and have wider benefits for society and the economy. However, this is not an easy task, and if the Scottish Government is serious about ensuring it, it needs to prioritise ruthlessly. Much of the narrative on tackling child poverty fits into the prevention narrative, meaning there should be savings on public spending down the line. But there will have to be difficult decisions made now on where spending should go if the child poverty targets are to be reached.

For more on policy, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have today released their annual report detailing a range of measures to reduce poverty relating to the pandemic and beyond: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/poverty-scotland-2020

For lots more information on topics relating to poverty, inequality and the pandemic the Economics Observatory, funded by the ESRC, has been providing answers to key questions https://www.coronavirusandtheeconomy.com/topics/inequality-poverty

Authors

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.