Fraser of Allander Institute, November 2016

Autumn Statement 2016 will be remembered for the unprecedented scale of its revisions to economic and fiscal forecasts, rather than its comparatively modest policy announcements.

Just eight months ago, George Osborne had laid out a budget that was expected to see the UK public finances return to surplus by 2019/20.

Forecasts published yesterday alongside the Autumn Statement leave that ambition (if it remained an ambition) in tatters. Forecasts for GDP growth have been revised down in 2017 and 2018, as a result of post EU-ref uncertainty and weaker consumer spending. Trade growth and migration are both expected to slow over the next ten years as the UK negotiates new trade deals post-Brexit.

Public sector net borrowing is now forecast to be over £100bn higher over the course of this parliament. The negative effects of the Brexit vote explain about £60 billion of this increase, with another £25bn of additional borrowing resulting from further weaknesses in tax revenue growth. Policy announcements explain a further £25bn increase in borrowing. Rather than a £10bn surplus in 2019/20, the government will run a deficit of £22bn.

Further consolidation is therefore likely. And whilst the OBR note that the Chancellor is on track to meet his new ‘Fiscal Rules’, recent history suggests that there is no guarantee that such rules will be met as current forecasts rely on painful tax and spend choices being delivered further down the line. On many occasions, when the time comes, decisions are either reversed or pushed back further.

There is always uncertainty in forecasts but this year there is greater uncertainty than normal. The OBR, the organisation charged with making economic and fiscal forecasts, is mandated to make its forecasts on the basis of current UK Government policy. But what is current UK Government policy on Brexit? In a thinly-veiled critique, the OBR notes that – despite having asked the UK Government for clarification, it is ‘little the wiser as regards the choices and trade-offs that the Government might make during the [Brexit] negotiations’.

Given this level of policy uncertainty, the economic outlook could of course turn out to be significantly better or worse than forecast. Some will argue that the OBR’s assumptions about the impact of Brexit are on the conservative side; the Institute for Fiscal Studies has forecast that Brexit will result in a larger negative effect on GDP growth than the OBR has estimated, and consequently higher borrowing.

The policy announcements by contrast were relatively modest. There was a further freeze in fuel duty and some marginal changes to Universal Credit; token gestures to support the so-called ‘Just About Managing Families’ that should be seen in the context of longer-term cuts.

The most significant policy announcement related to an additional £23bn of infrastructure spending, focussed on investments in housing, roads, digital infrastructure, and science and technology. The intention is to achieve a ‘step-change’ in the UK’s productivity record. Whether it is possible to achieve a step-change with an investment equivalent to 0.25% of GDP remains to be seen.

Implications for the Scottish Budget

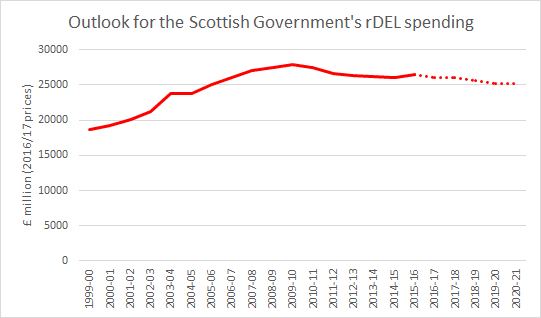

What does this mean for the Scottish budget? The Chancellor announced essentially no change to departmental resource spending relative to what had been set out by his predecessor in March. So the outlook for the Scottish resource budget remains unchanged. The block grant from Westminster will fall by around 3% in real terms between 2016/17 and 2019/20.

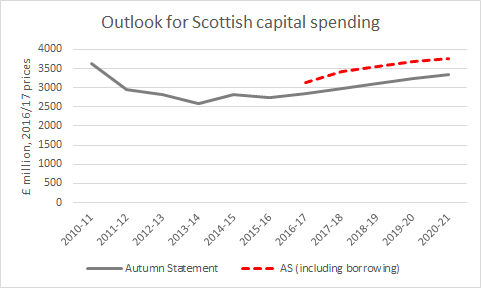

The Scottish Government’s capital grant will increase by £800 million as a result of the ‘consequentials’ flowing from the UK Government’s additional infrastructure spending. This will see the Scottish Government’s capital grant increase by around 5% – relative to what had been forecast in March – over the period to 2020/21. Significant this may be, but even by 2020/21 the Scottish capital grant will remain around 8% lower than it was in 2010/11. However, by utilising its new borrowing powers, the Scottish Government could achieve real terms capital spending in 2020/21 on the same level as ten years previously.

The Table below summarises the ‘consequentials’ – i.e. the additional spending that will flow to the Scottish budget as a result of yesterday’s Autumn Statement.

Autumn Statement consequentials for the Scottish budget (£ million):

| 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | |

| Resource | 0.7 | 27.2 | 28.0 | 17.7 | |

| Capital | 2 | 125 | 197 | 239 | 257 |

The subsequent charts show what this will imply for the evolution of the Scottish resource and capital block grants. These are based upon previously published figures for budget allocations and the consequentials above.

Note: Figure for Scottish Government’s allocation in 2020/21 based on FAI analysis of OBR forecasts for total departmental resource spending by the UK Government.

The Scottish Government’s total allocation from Westminster – including its block grant for resource spending and its grant for capital spending – will decline by just under 2% in real terms between 2016/17 and 2019/20. Between 2016/17 and 2017/18 however, the total allocation will actually rise fractionally, with the decline coming in the subsequent two years.

We will discuss these issues and more tomorrow at our post-Autumn Statement briefing.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.