Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are stressful events experienced in childhood, including childhood maltreatment and abuse and harmful home environments, that influence a multitude of present and future outcomes.

The 10 standard ACE measures are psychological, physical or sexual abuse, emotional or physical neglect, parental separation, domestic violence and living with household members who were substance abusers, mentally ill or suicidal, or ever imprisoned.

ACEs are highly prevalent in the UK. In a 2014 UK study, 47% of people reported at least one ACE and 9% of the population had 4+ ACEs. However, ACEs are more prevalent among children from deprived and lower socioeconomic backgrounds and those whose parents experienced ACEs. ACEs can have long run negative effects on health, wellbeing, and development. This creates substantial economic costs to individuals, through reduced opportunities and the inability to develop their human capital, and for the overall economy, due to a lower productivity labour force. Additionally, the associated health implications can also reduce labour productivity and significantly increase health care costs.

This article summarises the biological impact of ACEs, synthesises the existing ACEs literature and highlights the key findings and limitations from a research project studying the effects of ACEs experienced in early life on adolescent cognitive and non-cognitive development in the UK.

Biological Impact of ACEs:

The long run effects of ACEs are driven by the initial biological impact from the stress response to trauma in childhood. Prolonged exposure to ACEs during influential development periods, such as childhood, can alter brain development and result in long run changes to stress response regulation.

A normal stress response is a short-term survival response to a stressor, often referred to as the “fight or flight response”. These responses include increased production of adrenaline, raised heart rate and activation of the central nervous system. With a normal stress response, the individual returns back to normal levels through self-regulation buffers, established through effective coping mechanisms and parental support. However, prolonged, repeated or chronic exposure to stressors, such as ACEs, without effective returns to normal levels, can result in a prolonged or frequent activation of the stress response, known as toxic stress. When this stress response occurs during influential periods of brain development, without effective self-regulation buffers, this heightened stress response can become permanently ingrained into long-term biological processes and alter stress responses, resulting in adverse responses to any future stressors.

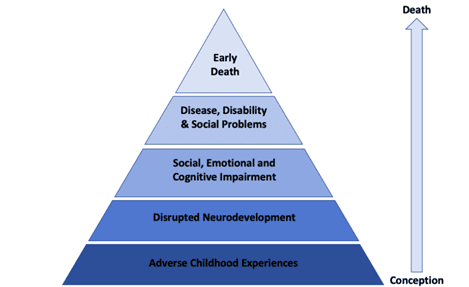

The potential consequences of these biological alterations following ACE exposure include impaired social and cognitive development and compromised immune systems, increasing the risk of adverse adult health outcomes and early morbidity. Figure 1 highlights this chain of consequences: exposure to ACEs disrupts and alters neurodevelopment, which has immediate consequences in childhood through impaired cognitive and noncognitive development. Reduced child development has consequences for later adult outcomes and opportunities and increases the likelihood of the adoption of health risk behaviours. This in turn increases the risk factors for disease, disabilities and social problems and subsequently increases the risk of early death.

Figure 1: The ACE Pyramid

Existing ACEs Literature:

There is an extensive empirical literature examining the impact of ACEs, measured both individually and as a collective ACE score, on a multitude of child, adolescent and adult outcomes.

The original ACE study surveyed US Health Maintenance Organisation members and developed the ACE score methodology, measuring the collective impact of ACE exposure on various adult health outcomes and examining how the magnitude of these effects varied by the number of ACEs participants were exposed to. Several studies have used this data to highlight that ACEs affect both adult mental health, through increased risk of depression and suicide attempts, and physical health, through increased likelihood of obesity and poor self-rated health. ACE exposure was also found to increase the likelihood of engaging in health risk behaviours such as smoking, alcoholism and drug abuse and sexual risk taking. The risk of all of these adverse outcomes increased with the number of ACEs experienced. ACEs were also found to increase the risk of early mortality: individuals with six or more ACEs were found, on average, to have died 20 years earlier than those with no ACEs and were at a 1.7 times higher risk of death by age 75 and 2.4 times higher risk of death by age 65.

Similar results of the collective ACE impacts have been found using other data. ACE exposure was associated with an increased risk of adult mental health problems and child and adolescent mental health and socio-emotional behavioural problems. Education and poorer school attainment were other key impacts of ACEs identified for children and adolescents. Additional adult health problems were linked to ACE exposure, including self-directed violence, cancer and heart and respiratory disease. ACEs were also shown to limit adult opportunities through increased risk of incarceration and reduced education and employment outcomes.

Several studies focussed on individual adversities to identify the potential links between specific childhood adversities and child and adult outcomes.

Exposure to family violence and experiences of physical abuse in childhood were found to impede both socio-emotional and cognitive child development. Evidence of long run psychological, behavioural, and academic impacts were found, such as reduced school attendance, lower likelihood of attending college and higher levels of aggression, anxiety and depression, social problems and criminal behaviour.

Sexual abuse was another common focus of childhood adversity studies with many studies identifying increased risks of metal health problems including depression, anxiety, sexualized behaviours, personality disorders, substance dependence and suicide attempts. Studies also examined the impact of neglect and emotional abuse and found an increased risk of early childhood aggression and reduced short and long-term cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioural development.

The majority of these studies discussed were focused on the US. However, there is also a substantial literature examining factors influencing cognitive and non-cognitive development in children in the UK, many of which used the longitudinal Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) data. ACE exposure increased the prevalence of child emotional, behaviour and mental health problems and reduced cognitive ability and performance.

ACEs Research Project:

I attempted to build on this literature in examining the impact of ACE exposure in early life on adolescent cognitive and non-cognitive development using MCS data. The results suggest that exposure to ACEs in early life was associated with reduced non-cognitive development and that each additional ACE in early life increased the probability of having a socio-emotional behavioural problem at age 17. Individuals with no ACEs had a 13% probability of having a self-reported socio-emotional behavioural problem. This increased to 20% for five ACEs and 27% for eight ACEs. The probabilities were smaller in the parent reported model but showed the same linear trend, increasing from 4% probability for no ACEs, to 8% for five ACEs and 12% for eight ACEs.

However, no such association was found for cognitive development, contradicting the previous literature. Data and methodological limitations in this study may have prevented the associations between ACEs and cognitive development from being identified. The MCS data does not capture all 10 standard ACEs identified in the previous literature, so fails to account for the impact of psychological, sexual or emotional abuse and neglect or incarcerated parents. Furthermore, the ACE measures examined are parent reported. Parents may have been incentivised to underreport their child’s exposure to ACEs due to the associated stigma, which could result in measurement error and an underestimation of ACE effects.

The collective ACE score methodology is an additional limitation. All ACEs are not uniform, but this methodology treats them as such, thus failing to account for differential abuse experiences or the increased impact certain ACEs have over others. Future studies would benefit from adapting this methodology. Each ACE should be weighted based on the general impact of that ACE relative to others, for example, sexual or physical abuse, compared to parental separation. Additionally, weights should be used to account for the severity, frequency and duration of each individual’s ACE exposure and then group individuals based on the similarities of their experiences. Combining these weights could capture the general differences in ACEs and the individual’s trauma experiences. However, further research is required to understand these differential impacts to determine these weights.

Despite the limitations of this study, it is evident from the literature that ACEs are an important consideration in policy design. Impaired child development creates an economic cost to individuals, through the inability to develop their human capital, and the overall economy, due to a lower productivity labour force. Additionally, the associated health implications can also reduce labour productivity and significantly increase health care costs. ACEs are highly prevalent within UK society, creating a large population who are inherently more likely to respond adversely to stress and to experience adverse life outcomes. The substantial long run economic costs of ACEs provide justification for early intervention to prevent ACEs and help children with ACEs develop resilience and effective coping mechanisms to mitigate their long run impact.

Click here for the full perspective and references.

Authors

Ciara is an Associate Economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She has a broad research experience across different areas including poverty and inequality, the voluntary sector, health, education, trade, and renewables and climate change. Ciara has an MSc in Applied Economics (Distinction) and a first-class BA Honour’s degree in Economics and Finance, both from the University of Strathclyde.