The aspiration of a ‘4-day week’ has been gaining traction. Think tanks have argued in favour of the idea for the UK, and books have extolled the virtues of shorter working hours. Spain has recently announced a modest pilot of a 4-day week.

The idea of a four-day week has firmly arrived in Scottish political discourse. The SNP Manifesto, published today, commits to establishing a £10 million fund to allow companies to pilot and explore the benefits of a four-day working week. The pilots will inform the implications of ‘a more general shift to a four day working week as and when Scotland gains full control of employment rights’ and an assessment of ‘the economic impact of moving to a four day week’. Yesterday’s Green Party Manifesto committed to ‘Support the transition to a four-day week with no loss of pay’.

But what is a 4-day week? And is it an idea that is workable? This blog draws on some of the findings from our ongoing project on working hours, funded by the Standard Life Foundation, to shed some light on these questions.

So what is a four-day week?

When people talk about a 4-day working week this is usually short-hand for a world where people typically around 30 hours per week, with flexibility over when to work those hours.

Moving to a 30-hour week would be a big change for most. The typical (median) male employee in Scotland works about 38 hours per week, or 35 hours amongst females (the typical female full-time employee works 37 hours per week).

The case for a four-day week

The case for a shorter working week is based around a number of observations.

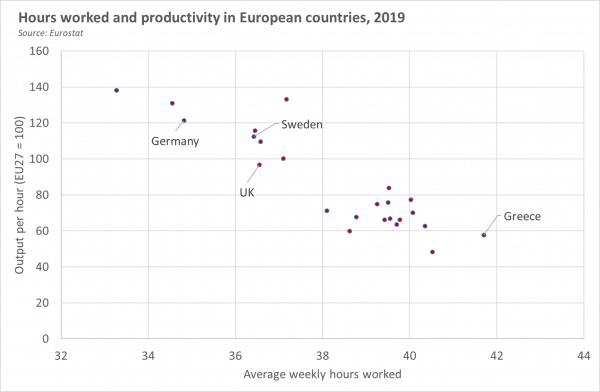

First is the idea that people might be more productive if they work shorter hours. Cross-country evidence shows that countries with shorter working hours are on average more productive (i.e. they produce more per hour) than countries working longer hours.

Second, there’s evidence to suggest that measures of happiness, or life satisfaction, tend to increase when people work fewer hours. In this sense, policies and institutions that facilitate shorter hours can be seen as a way of coordinating on a more socially desirable outcome than would arise without this framework.

More recently, shorter working weeks have also been proposed as a means of maintaining high employment in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Seen in a historical context, the move to a four-day week is simply the continuation of a longer-term trend

Increased productivity, happier employees – what’s not to like about a shorter working week?

Indeed, in many ways the gradual transition to a shorter working weak is a sensible and worthwhile aspiration for a government to have. After all, the transition to a 30-hour week is the direction that society has been heading towards for many decades.

Back in the 1930s, Brits worked around 49 hours per week on average, having fallen from 58 hours at the beginning of the 1900s. Keynes famously predicted we’d be working as few as 15 hours by 2030. He was right about the direction of travel, but wrong about how quickly we’d get there.

Policy and institutions do play a big role in influencing hours. Back in the 1960s and 70s, workers in Germany and France worked similar hours as those in the UK (and US). Since then, hours worked have fallen more rapidly in Germany and France. In both countries, union movements placed significant emphasis on reducing working time, and in France in particular this coincided with an emphasis on regulation to incentivise working time reductions. Today, many of these historical differences in hours negotiations persist in the way that the European Working Time Directive is implemented. Today, male employees in the UK and US work around 42 hours per week on average, compared to 39 per week in France, Germany and Sweden (country differences for full-time female employees are similar).

(Side point: some have argued that, although US workers tend to work longer hours than Europeans, they don’t necessarily have less ‘leisure time’, as they have a greater tendency to buy-in support for household jobs like home repairs, cleaning and cooking… one difficulty in testing this theory is working out to what extent certain tasks – like cooking dinner – are perceived as chores or pleasure.)

Of course, working hours are affected by factors other than ‘policy’. Incomes matter too. The persistent fall in working time during the 20th century was made possible by real wage growth which enabled people to trade off working time for increased leisure. And the main hypothesis as to why male hours stopped falling following the Great Recession (and why the growth in female hours worked accelerated since then) is that real wage growth stagnated.

Productivity, hours and earnings

This takes us back to the earlier point about productivity. Correlation does not imply causation, and there’s no guarantee that working less will increase productivity in itself. Indeed in a number of sectors – particularly health, social care, education, personal services, the arts – the scope for productivity improvements is likely to be pretty limited.

A reduction in working hours without commensurate increases in productivity is likely to require some combination of reduced earnings, increased public funding, or reduced profits. The latter margin is not available in the public sector – or in economically marginal sectors.

In reality, most people are likely to be unwilling to see falls in working hours if that means falling income. It is true that, in 2019, 13.5% of Scottish employees were overemployed – they would happily work fewer hours even if it meant less pay. But the remaining 86% of employees did not want shorter hours if that meant less pay – and in fact 8.5% wanted to work longer hours. Underemployment is associated with increased risks of anxiety and depression.

Shorter working weeks would pose challenges too in relation to labour supply. Encouraging doctors to work shorter weeks is all well and good, but assuming (very reasonably) that their productivity won’t increase in response to shorter working time, then its no good thinking that shorter hours can be offset by simply employing more doctors, at least in the short term.

Labour supply issues might also dampen the impacts of reduced working hours in enhancing productivity – if for example productivity is partly a function of joint working and coordination amongst workers.

Directly subsidising a transition to a shorter week?

The observation that most employees would not want to work fewer hours if it meant a loss of earnings has important implications for how we get towards the idea of a shorter working week.

Some argue that a shorter working week is something that governments should ‘implement’ quite directly, for example by subsidising employers for an extended period to support the transition to shorter working time. But it seems unlikely they’ll be political appetite for such a direct, high cost strategy outwith a pandemic (although this is the direction that the Green Party Manifesto seems to suggest).

Or facilitating it less directly?

Instead, the role of government should be to facilitate the conditions for the change to happen – when and if employers and employees collectively want it to.

How might government’s play this facilitative role? Broadly, it means policies to support pay growth, both through productivity enhancements and further increases in the statutory minimum. It means a focus on measures to give employees greater control over the hours that they work – the UK Government’s promised Employment Bill provides a neartime opportunity to introduce relevant measures in that respect. It means renewed and reinvigorated institutions to improve collaborative working to agree and uphold working standards – as the OECD points out, collective bargaining can be an effective way to improve working practices and ensure that those practices best reflect societal preferences. And in some cases it will require extra public funding – under-funding of social care is already impacting care outcomes and encouraging some employers to rely on working practices that require long hours and transfer financial insecurity onto employees.

The the sector-specific requirements of employers can’t be neglected either. As noted above, some sectors will find it extremely difficult to transition to a shorter week without an increase in the available pool of labour, and many industries do benefit from a somewhat standardised working pattern so their employees can collaborate.

But ultimately, the question isn’t really whether a 4-day week is a worthwhile policy aspiration. The more relevant questions are how does policy facilitate that to happen, over what timescales, and at what cost. A 4-day week won’t be the norm in five years time without a deterioration in living standards. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t a sensible goal around which to frame labour market and wider economic policy.

Authors

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Mark Mitchell

Mark Mitchell is a former research associate at the FAI. In 2021, Mark moved to a post in the Competition and Markets Authority. His research area is applied labour economics, focussing on the causes and effects of human capital accumulation over the lifecourse.