Graeme Roy

Director, Fraser of Allander Institute

There has been a lot of debate in recent days about the statistics covering Scotland’s fiscal position i.e. Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS).

Some of this has focussed upon how GERS is produced and who produces it – this blog attempts to clear some of that up.

An important disclaimer!

Before we begin, a disclaimer.

My first job as a civil servant in the Scottish Government was in the GERS team back in 2007. I continued to be involved in its publication up to 2014. So I know a bit about how it works and what it does and doesn’t do.

What is GERS?

In short, GERS estimates the contribution of public sector revenue raised in Scotland toward the public sector goods and services provided for the benefit of the people of Scotland.

It’s important to remember that GERS does this taking Scotland as a mini-UK, and the constraints and protections that the current constitutional arrangements bring.

It’s a National Statistics publication. This means that the statistics – and how they are presented – have been independently judged to be methodologically sound and produced free of political interference.

It is published at the discretion of the Scottish Government – no-one ‘forces’ it to be produced.

Who produces it?

GERS is produced by civil servants in the Scottish Government.

They alone are responsible for pulling it together, not the UK Government (or anyone else for that matter).

The statisticians I worked with on GERS were – without question – some of the most talented, professional and hard-working colleagues I’ve ever met.

Over a period of months, the statisticians go through thousands of spending lines to ensure that the correct figures are used for Scotland. Much of this built on the excellent work of Jim and Margaret Cuthbert who worked tirelessly to critique the original methodologies used and to offer better approaches.

Each identifiable spending line is now scrutinised, checked and double-checked. On many occasions, this means taking a different tack to UK statisticians. For example, HM Treasury allocate the costs associated with decommissioning Dounreay to Scotland. GERS takes the view that as Dounreay is a UK wide nuclear facility a more appropriate allocation is a per capita share (resulting in a lower spending figure for Scotland).

For each non-identifiable expenditure – e.g. defence/foreign affairs – the same civil servants decide on the most appropriate methodology to use. For most elements, they decide to use a per capita share. For example, using the assumption that someone in Scotland benefits in exactly the same way from spending on the defence of the UK as someone living in Wales, England or N. Ireland.

On revenues, each tax or other public sector income stream is estimated separately. Methodologies are chosen because of their robustness but amended as and when better data become available. All changes are peer reviewed by an external group of experts.

Any suggestion that the figures are subject to interference or influence is simply wrong.

A BRIEF ASIDE

Work with us

We regularly work with governments, businesses and the third sector, providing commissioned research and economic advisory services.

Find out more about our work as social and economic impacts consultants.

Why are estimates used?

It’s important to note that – on the spending side at least – most of the figures aren’t estimated.

- £40.5bn of spending in GERS is devolved (or around 60% of the total) and incorporated directly.

- For the £17.8bn of UK welfare spending in Scotland, detailed and robust benefits information is used to identify where claimants actually live and how much they receive etc.

- For the vast majority of other reserved spending – e.g. defence and debt interest etc. – the data is known, where the estimation comes in is simply how it is apportioned.

On the first two of these, we know that on balance Scotland spends more per head than the UK because of the Barnett Formula and our slightly higher number of people entitled to benefits associated with issues such as long-term ill health etc.

But it is the case that for most revenues, estimation is needed.

People are right to highlight the need to improve the coverage of Scottish economic statistics. Although great strides have been in recent years via the Scottish National Accounts Project, more work needs to be done.

But it’s wrong to dismiss GERS out of hand simply because they rely, in part, on estimation.

Firstly, estimates are not unusual in economic statistics. Scottish GDP figures are based entirely on estimation, as are the productivity, trade, employment, unemployment and national income statistics. And Scotland is not unique, all countries rely on estimates – including UK GDP!

Secondly, there’s a good reason (under the current constitutional settlement) why estimation is used – collecting data for the purposes of a statistical publication can only be justified if costs are proportionate. Collecting real-time data on alcohol duties for example, would require monitoring each and every alcohol sale in Scotland (and cross-border sales). This would be required for every betting and gaming transaction, tobacco purchase, when you filled up your car with fuel and so on.

The key issue therefore, is whether or not these estimates are robust.

In my view, the methods used are the best available. You are welcome to agree or disagree – the statisticians are fully transparent about what they use so you can check for yourself.

It’s also possible to do a number of checks to reassure yourself on the numbers.

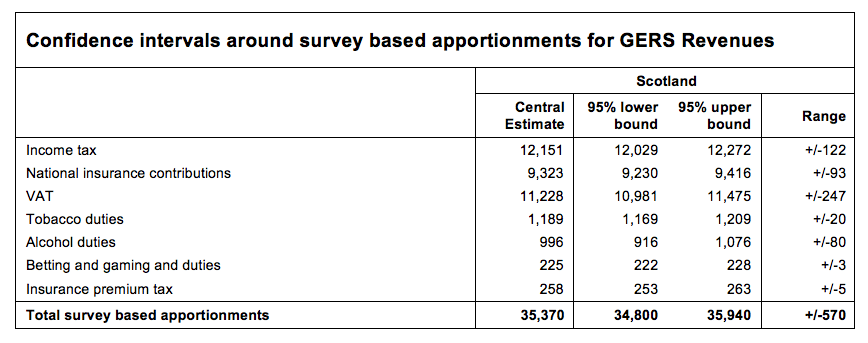

For example, GERS publishes 95% confidence intervals for many of the ‘big’ taxes that rely on estimation.

To put this in context, £570m is equivalent to 0.4% of GDP.

Back-of-the-envelope calculations also provide some useful context.

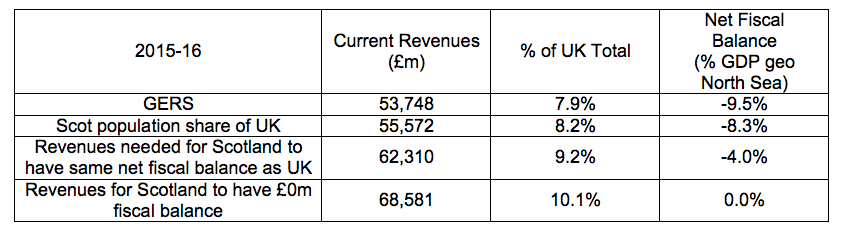

GERS estimates Scotland raising 7.9% of UK revenues – just below a per capita share.

Given Scotland’s GDP per head is in line with the UK’s (slightly higher with North Sea oil, slightly less onshore), this number seems sensible – particularly once you factor in the City of London’s predominance in paying income and corporate taxes and the fact that, whilst Scottish average earnings and employment broadly match the UK, we have fewer people at the top of the income distribution and asset prices are slightly lower.

But even setting aside the GERS estimate, if Scotland did raise a per capita share of UK revenues (8.2%), Scotland’s estimated net fiscal balance would only fall from -9.5% to -8.3%.

So alternative figures and estimates can be arrived at – and for some individual taxes like corporation tax the estimates are more uncertain – but any changes are small and don’t alter the big picture.

What about expenditure? Again, different assumptions and methods will have an impact, but again only at the margin.

Take two examples, defence and debt interest repayments. If Scotland was to be allocated no such spending, the deficit would stand at -6.2% of GDP (exc. North Sea revenue) and -5.7% of GDP (inc. a geographic share of North Sea revenue).

Debating GERS

GERS is not perfect – it doesn’t claim to be.

But even significant differences in estimation – and well outside that which could be considered statistically reasonable – don’t change the overall headline figures.

Until recently, informed debate over GERS had focused on the principles in the methodology adopted rather than statistical accuracy – e.g. is it appropriate to allocate Scotland a per capita share of defence expenditure if the UK’s defence footprint is slightly lower in Scotland than elsewhere, or is it appropriate to allocate Scotland a per capita share of UK debt interest repayments if Scottish public spending has been higher than the rest of the UK?

Debate has also concentrated on whether a one-year snapshot is appropriate or if instead account should be made of Scotland’s past fiscal position – including the years of recent deficit but also the ‘estimated’ large surpluses in the early 1980s.

These arguments are entirely legitimate, and ‘fairness’ is something we each may have an opinion on, but to criticise the entire GERS exercise for the simple fact that they are based upon ‘estimation’ is clearly wrong.

Conclusions

There are important debates to be had about what GERS tells us – both about the current health of Scotland’s economy and options for constitutional reform.

Do the GERS numbers demonstrate the benefits of pooling and sharing or do they highlight Scotland not fulfilling its potential?

What different fiscal choices might a more autonomous Scottish Government take?

What might be the costs and benefits of making these changes and/or implementing a new constitutional framework?

How might faster/slower growth impact on the results in the future?

What does GERS not tell us: What about Scotland’s balance sheet – i.e. the assets and liabilities of the nation? What about Scotland’s private sector accounts – how much national income do we receive each year? Who owns this wealth and how is it distributed?

These are the sorts of questions we should be debating. Questioning the integrity and robustness of National Statistics is not one of them.

Authors

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.