Imagine you’re heading out for a walk. You really want it to be dry, but your weather forecast app says it’s more likely than not that it will rain. You chance it, but five minutes later it starts lashing it down.

You could get angry at the Met Office, but that doesn’t feel especially rational. It certainly won’t make you any less wet. Bringing a rain jacket would have, but now you have few good options. You can pop in somewhere to buy an umbrella; you can turn back and leave it for another time; or you can try and persevere through it, in the knowledge that it might be quite unpleasant and potentially dangerous.

The role of the OBR is not to do the Government’s bidding

As zany as this parable might seem, it’s not a million miles away from the reaction we have seen in some quarters to what is likely to be a fairly troubled Autumn for the Treasury.

(Full disclosure – we’re both former staff of independent fiscal institutions. But that experience also brings with it an appreciation of what is and isn’t the role of an official forecaster.)

Last year, the OBR revised up its judgement for potential output relative to its baseline as a result of the Chancellor’s boost to public spending – particularly on investment – and some of the measures announced on planning reform.

Few economists would disagree that planning reform and sustained capital spending will boost productivity in the medium and long run. But this came against the backdrop of many years of productivity growth underperforming the OBR’s assumptions.

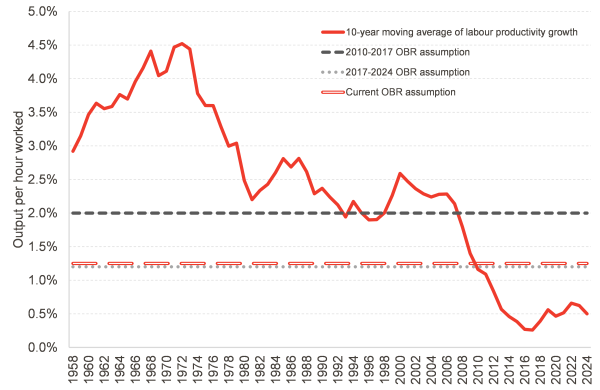

The OBR originally assumed output per hour worked would grow at 2% a year in 2010. Years of disappointing outturn data led to this being revised down to around 1.2% a year in 2017. But even that has proved wildly optimistic: UK productivity growth has not consistently averaged 1.2% a year since the year of the OBR’s creation, and it currently is hovering around 0.5%.

Chart 1: Long-term averages of productivity growth compared with the OBR’s assumptions

Source: FAI analysis of OBR, ONS and BoE data

It is therefore surprising to see recent arguments that there is too much uncertainty for the OBR to revise down its productivity judgement at this point, in a blog published last week by the IPPR. There are two main premises underlying this blog:

- A lower productivity path would make the UK Government’s plans for the path of debt harder to hit, and the Chancellor would then have to tighten fiscal policy;

- The UK Government’s policies are likely to increase productivity relative to where it currently stands.

As previously mentioned, (2) is probably true. In fact, the OBR said as much in its recent forecasts, and hence why it increased its assumed productivity growth from where it previously was.

But the problem with the current assumption is one of levels, not of relative growth from outturn. It is just implausible that the UK Government’s increase in investment – which while high by historical UK standards, is still some way off other advanced economies’ – and its promised planning reforms will increase productivity 2.5-fold.

Of course, it would be great if it happened, but a jump of this magnitude is simply not credible. In fact, the OBR’s credibility is on the line here: it has been so over-optimistic on productivity for so long that to continue along those lines would make it seem to be in the pocket of the Government – and that would undermine its role as official forecaster.

As for (1), it is not for the official forecaster to decide whether policy is too tight or too loose, nor is it its fault that successive governments have run fiscal policy that is likely too loose for too long. The reality is that the UK has run a deficit of over 3% of GDP in 14 out of the last 18 years if we include the current fiscal year. Public sector net debt is close to 100% of GDP and interest rates have increased significantly over the last few years. Gilt holders have been getting jittery both around and outside of major fiscal announcements. The UK Government then decided to loosen fiscal policy significantly last year, despite all of this, and is now finding it hard to pass the legislation required to meet what are already very lax fiscal rules by historical standards.

None of this has to do with the OBR – it’s a set of fiscal policy choices, which successive occupants of 11 Downing Street must own. The reality is hard, but pretending that our productivity growth hasn’t fallen off a cliff since 2008 will only make the reckoning harder when it does come.

The UK’s problem is not the fiscal rules, but fiscal policy

Don’t get us wrong – we agree that the narrow focus on compliance with the fiscal rules is bad, and that it leads to poor choices in fiscal policy terms. A focus on ‘headroom’ and on doing everything possible to comply with the letter of the Budget Responsibility Charter is a large part of the reason for the rushed welfare cuts announced in March.

And because the fiscal rules are assessed by the OBR, it is tempting to think that just abolishing the institution would make the issue go away, as suggested in an article by the New Economics Foundation this week. Often reporting of fiscal forecasts pits the OBR as forcing the Chancellor to change her policy, which can give an impression of the OBR having some sort of de facto veto on fiscal policy.

But this reporting misunderstands the role of the OBR, the Treasury and the gilt markets. Rachel Reeves’ fiscal rules are already very loose, and they are barely complied with in the OBR’s forecasts.

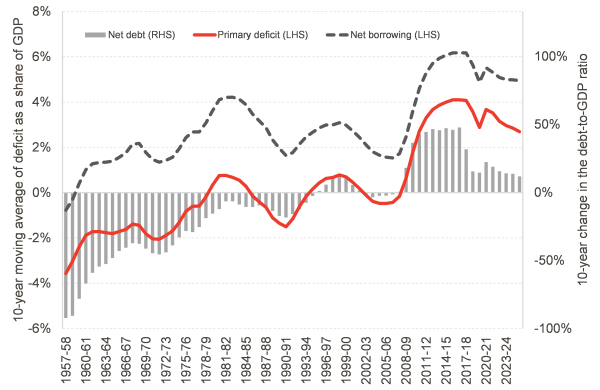

Chart 2: Long-run deficits and change in debt

Source: FAI analysis of OBR, ONS and BoE data

Instead, the issue is that UK fiscal policy has been very loose since the turn of the century. Net borrowing has averaged 4.8% of GDP since 2000-01, and 5.9% of GDP since 2008-09. Unsurprisingly, this has led to significant debt accumulation: from 28% of GDP at the turn of the century to 95% as of March.

Higher GDP growth tempered the issue in the 2000s, but the abrupt fall in productivity after the Financial Crisis has meant that this large structural deficit increased, bringing with it a larger debt stock. When the era of low interest rates ended, the UK’s vulnerabilities were exposed: the primary deficit (that is, excluding net interest payments) has actually fallen in recent years, yet the overall deficit has remained stubbornly high.

The United States may be able to sustain large deficits for a long time, but the UK’s place in the world economy is far from the anchor role played by the US. It is therefore hard to see how structural deficits like this can be maintained without debt holders demanding much higher interest rates and becoming nervous about the UK’s ability to make good on its payments.

This interacts with the viability of proposals to make the UK’s fiscal architecture less constraining on the Chancellor. Even Rachel Reeves’ ability to live with not complying with her fiscal rules – which she does have in principle – is undermined by the UK’s weak position in international debt markets. It would be one thing to abolish a fiscal council halfway into a successful long-term debt reduction plan. But the suggestion in the article is that Rachel Reeves should abolish the OBR in order to borrow more, not less. How well will that play out with holders of UK debt, in an environment where less than £5 billion a year in additional borrowing tips the markets into meltdown? It is reminiscent of the sort of thinking that underpinned the 2022 ‘Growth Plan’, and we all know how that turned out.

Even if we fully abstract ourselves from economic developments in the last few months, a glance of chart 2 would tell you that the UK is likely to have to face up to a tighter fiscal policy come the Autumn. That could mean lower spending or higher taxes. And with the welfare reforms watered down and the Spending Review just concluded, the former seems pretty hard politically. So it’s likely we’ll see taxes rise, as has been briefed continuously in recent times.

With the economy not doing too well, it’s probably not what the textbook would recommend in terms of fiscal policy. But the price of running a large structural deficit is that fiscal space runs out when you need it the most. And even if you’d want to do the opposite, the markets might just force you into tighter fiscal policy – OBR or no OBR.

We all wish it was going to be a sunny Autumn – no one wants the rain to fall on their head. But let’s not blame the forecaster when they tell us it’s on its way.

———————————————————————————

Don’t forget, The Fraser of Allander Institute celebrates 50 years of leading economic research in Scotland in 2025.

As part of our programme of events, we’re hosting our own conference at The University of Strathclyde’s Technology and Innovation Centre on the 18th and 19th of September 2025.

To find out all of the details, including the planned programme for the day and how to register, visit our conference page.

We look forward to celebrating with you!

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.