The IMF waded this week into a live debate in UK fiscal architecture, with Fiscal Affairs Department Director and former Portuguese Finance Minister Vítor Gaspar firmly in favour of maintaining two forecasts a year. This comes off the back of reports in July that Rachel Reeves was considering scaling the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) role to producing one forecast a year, which for proponents might help reduce the zig-zagging in fiscal policy typified by the Spring Statement.

There are competing views among the UK’s fiscal community: for example, Institute for Government (IfG) Chief Economist Gemma Tetlow has made the case that one forecast a year may be the only long-lasting solution, while the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) argue for the merits of two forecasts but just one policy event.

Our view – as we’ll discuss – is that there are UK-specific reasons why two forecasts a year but only one policy event is not an equilibrium, and so we are more in line with the IfG’s view. But before that, how did we get to having two forecasts to begin with?

A legacy of inflation in the 1970s

The Industry Act 1975 was the vehicle for enshrining into law the requirement of conducting two economic forecasts in any given financial year.

Ostensibly, this now largely repealed piece of legislation was concerned with establishing the National Enterprise Board. But it’s schedule 5 that really stood the test of time, eventually ending up in the Budget Responsibility and National Audit Act 2011.

Schedule 5, article 6 of the Industry Act 1975 required that the Treasury to produce economic forecasts using a full macroeconomic model (maintained on a computer, no less) at least twice a year.

But why?

The high inflation of the 1970s meant that forecasting public spending once a year was no longer appropriate. This was particularly true in the then framework for public spending:

- Prior to the beginning of the year, Estimates were presented on the basis of constant prices and forecast inflation;

- Close to the end of the financial year, the Government would commit to making good on any unanticipated inflation for all programmes.

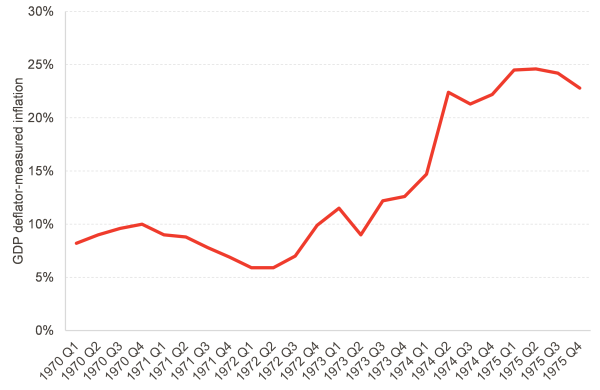

Chart: GDP-deflator measured inflation in the early 1970s

Source: ONS

But with inflation running rampant and accelerating within financial years by as much as 10 percentage points, year-old forecasts were clearly too out of date. So the requirement to present forecasts more frequently made sense.

Legislation breeds permanence

The Industry Act forecasts stuck around, largely as a result of the legislative provisions, always accompanying the Budget Report and the supplementary fiscal statement. But it wasn’t until Gordon Brown’s tenure that the second forecast rose in prominence.

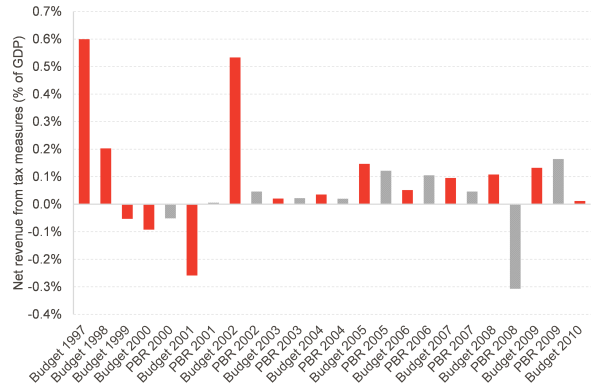

Chart: Net revenue raised in each budget and PBR during the 1997-2010 Labour Governments

Source: OBR, FAI analysis

The Pre-Budget Report, or PBR, as it was known, was meant as a way of collating the government policies that were being consulted on for the upcoming Budget. But over time, it became another Budget in all but name, particularly after 2005. The chart above is pretty clear that there is little difference in the size and scope of events.

Since 2011, the Act of Parliament that put the OBR on a statutory footing has included a requirement for it to produce two forecasts a year, meaning that any change would need to amend that Act or repeal that part of it. The obligation is on the Office, hence why there was a slightly farcical supplementary forecast in the 2019-20 financial year.

A political economy equilibrium?

Vítor Gaspar and other commentators are correct that international best practice is to have multiple updates to forecasts a year. But international best practice is an aggregation over multiple jurisdictions, and following it without giving due consideration to the UK’s institutional setup can well lead us into a suboptimal settlement.

First, the role of the OBR is stronger than that of other forecasters. It is in fact one of the world’s strongest independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) in terms of their direct voice in the process. The Treasury is mandated to use the OBR’s forecasts at a commissioned fiscal event, which directly binds the OBR and the Treasury into the process. This is unlike most other setups, in which IFIs comment on the reasonableness and forecasts after the fact.

This means that OBR forecasts are the forecasts in the Treasury’s statements and in the Chancellor’s lips when updating the House of Commons. This again reinforces the OBR’s place in the process – confront that with the “wishful thinking” economic projections of the 2022 mini-budget without OBR involvement and how those were received.

This is not some odd quirk of the process – it’s fundamental to understanding the incentives that govern it.

As we discussed when we talked about fiscal rules last year and in March, successive Chancellors have felt it politically untenable to present a document which shows their targets being missed. In some cases, formal legislated targets were missed, but they were always superseded by informal, real targets that drove policy.

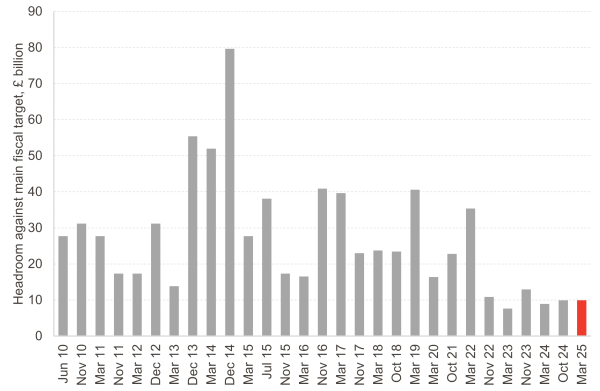

Of course, this has been made worse in recent years by the ever-shrinking amount of buffer Chancellors have left themselves against breaking their fiscal rules, which has made this question even more pertinent. But the characteristics of a system and its incentives only really come to the fore when constraints bind, and so it is natural that the current experience is testing the framework.

Chart: Headroom against the main fiscal target since 2010, with the latest fiscal event highlighted

Source: OBR

The system’s incentives feed tinkering impulses

And it is here that the UK’s fiscal architecture interacts with its parliamentary system in a way that makes not responding to a forecast showing a target being missed a near impossibility for a Chancellor.

The UK’s Parliamentary and budget-setting systems are, for the want of a better word, strange. Parliamentary timetables and business of the House of Commons are set by the governing party almost completely, and are governed by malleable conventions rather than fully laid-out rules. This agenda-setting power means the government always has the ability to make time for a statement that responds to forecasts, so it makes it all too enticing for the government to take action rather than end up with a bad financial news story.

In a more coalition-based system, the difficult in agreeing to even open up negotiations on fiscal matters might work as a check on the temptation to respond. The government might be wary of ending up in a position where nothing is agreed and a negative outcome from such a negotiation – which inevitably would be known to happen if multiple parties are involved. But the UK’s majoritarian system makes that a non-starter: the governing party has to command the confidence of the Commons for the Budget, and that makes its passing a given. So horse-trading happens does not happen in such an open way; rather, it takes place around Cabinet and in the confines of the Treasury.

And the legislative process itself and how Chancellor statements fit with that further reinforces the incentives to act when a forecast would show a missed fiscal rule. Unlike other countries’ fiscal statements, a Budget Statement in the UK is more of a statement of intention than a fully fledged legislative device.

Budget Acts in other jurisdictions have fully fleshed out budget tables for each government programme. But that’s not what happens in the UK. The full tables don’t get published until Main Estimates, and even then they are expected to be revised. Plans published in PESA in July are always already different from the previous month’s Main Estimates, and they get revised multiple times until Supplementary Estimates.

Likewise, legislative proposals from the Budget come months down the line in the Finance Bill, and sometimes announcements from one Budget are only legislated for years later in a subsequent Finance Bill.

All this adds up to make the cost of making a statement changing policy very low. There is always legislative time (or it can be created); there is little outward cost of testing out these policies and trying to hit a target; and they proposals don’t need to be fleshed out to be announced. So it’s no wonder Chancellor struggle to see the downside of responding to a forecast that shows them missing their rules by adjusting policy. Bad macroeconomics, but probably a political economy equilibrium.

‘Halfway-house’ approaches are unlikely to be sustainable

This is why we are sceptical of the feasibility of some of the proposed approaches, such as the IMF approach of only formally assessing the fiscal rules once a year but sticking to two forecasts a year, or the proposal to define being slightly in deficit as needing no immediate action in line with the Charter for Budget Responsibility’s revision from Spring 2027, and which the IFS supported bring forward.

These proposals are elegant, but they fail to account for the political issue that even without a formal breach of the rules, Chancellors will have an incentive to go out of their way to adjust policy so they can meet the rules and avoid getting the inevitable stick of getting out on a technicality. It’s too nuanced to communicate, and too easy for the other side of the House not to use it to score a political point.

We just don’t think these are a political economy equilibrium. If we want less tinkering with fiscal policy to meet arbitrary targets, and if we agree that means reducing fiscal policy events (in normal times) to one a year, then we might just have to live with one forecast a year from the OBR.

Of course – as NIESR point out – a bigger buffer would do wonders to avoid this tinkering, and there are indications that the Chancellor might finally be taking action to achieve this. That’s sensible policy. But if we want to have a resilient system, we need to think about the incentives when the system is under stress. And that means also understanding when something is an equilibrium in political terms – and when it isn’t.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.