One of the roles we play on a day with big fiscal announcements is to explain all the numbers flying about from different politicians – to set out which numbers are illuminating, and which are misleading. Often the biggest culprit is large numbers which represent spending over several years.

Wednesday was sadly no exception to this, and no political side covered themselves in glory – transparency was public understanding were the real losers of the numbers thrown about. And as usual, we lost count of the number of times we said “two things can be true at once”.

So just, to be clear, here are the real numbers of interest for the Block Grant.

Table 1: Scottish Government Block Grant, £ billion

| 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 | |

| Block Grant | 48.1 | 49.8 | 50.8 | 52.1 | |

| Resource | 41.5 | 42.7 | 43.8 | 45.0 | |

| Capital | 6.5 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

Source: HM Treasury

How can we summarise these changes?

There are many sensible ways to describe these numbers. Broadly, all the following are true and accurately represent the size and profile of the Block Grant:

- The Scottish Block Grant is increasing by £4 billion over the three years of the spending review period, reaching to £52 billion by the end;

- This is an 8.3% increase in cash terms, and around 2.7% in real terms over three years;

- This is the equivalent to 0.8% annual average real terms growth in the Block Grant;

- Resource spending is increasing by over £1 billion in each year of the SR period;

- Capital spending increases by £0.6 billion in 2026-27 but is roughly flat in cash in the subsequent two years, which means a real terms cut in the latter half of the spending review period in capital spending.

It is therefore disappointing to see some of the ways that the Treasury chose to portray the increase in funding through the Block Grant in its press release:

The Scottish Government will receive the largest real terms settlement since devolution began in 1998, with an average £50.9 billion per year between 2026-27 and 2028-29, enabling the Scottish Government to deliver for working people in Scotland. This includes £2.9 billion per year on average through the operation of the Barnett formula, with £2.4 billion resource between 2026-27 and 2028-29 and £510 million capital between 2026-27 and 2029-30.

If we take these in turn:

- Every year the Block Grant is likely to be the largest settlement since devolution, even in real terms. See our blog on the previous iteration of this inane debate, but the short version is that comparing the Block Grant with its own size over the past quarter of a century tells us very little about how resources are prioritised. GDP has grown a lot in real terms since then, and so has government spending as a whole. So a share of GDP or share of departmental spending is a much more meaningful presentation.

- The £50.9 billion number is an average across three years, which is a strange way of presenting this – forecasters such as the OBR and SFC tend to focus on the steady-state point at the end of the period, for good reason.

- The £2.9 billion (we think) takes the Block Grant in 2025-26, compares that to the three years 2026-27, 2027-28, 2028-29, adds this up, and then averages it out, and so suffers from the same issue as the previous statement.

While these are numbers aren’t particularly great exemplars of insight, they still tell us broadly what is going on. The same cannot be said about the £9.1 billion of ‘additional’ funding for the Scottish Government that we heard claimed in the media. This takes the Block Grant in 2025-26, compares that to the three years 2026-27, 2027-28, 2028-29, adds these three figures together, and then also adds in the capital uplift in 29-30 compared to 25-26.

It’s not that the numbers don’t add up to £9.1 billion or that the £9.1 billion won’t be transferred into the Block Grant. It’s that no one could credibly claim that what would have happened in the absence of any changes in the Spending Review would be that the Scottish Block Grant would have stayed at £48.1 billion for three years. The DEL figures were clear for everyone to see in the Spring Statement – so it’s not additional in any meaningful sense of the word.

We perfectly understand that politicians will want to use numbers which illustrate a political point – that is their right, and we are here to point out when a partial picture is being described. But it is harder to understand why confusing or non-meaningful claims are made when there are plenty of sensible numbers that could make the same point.

Has Scotland been short-changed?

The claim from the Scottish Government, on the other hand, is that ‘Scotland has been short-changed by more than a billion pounds’, although it’s unclear how this was arrived at – even if one accepted the premise that it’s on the basis of what average growth is for UK Government departments.

But the premise itself is deeply problematic. For one, comparing the Scottish Block Grant to overall RDEL and CDEL is not meaningful in any sense, because total departmental spending includes many areas for which there are no equivalent devolved competencies – and some of those, such as defence, have seen some of the largest increases. It’s not like money has been moved geographically from Scotland to England – instead, more money has been allocated to reserved areas, which cover both Scotland and the rest of the UK.

A much more representative – although harder, as we can tell you from experience having done it ourselves – is to look at how the Scottish Block grant compares with UK Government departments that have similar responsibilities on a per person basis.

Both factors are important. For one, only about 70% of UK Government departments’ spending has devolved counterparts. But because Scotland’s population is only forecast to grow by 1.3% by the end of the decade – half the rate of population growth in England and two-thirds the rate in Wales – just looking at totals can be misleading.

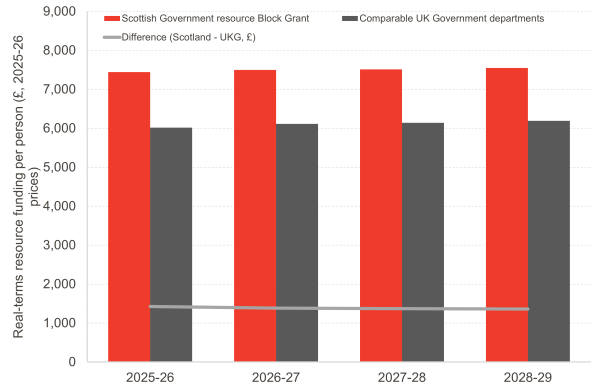

On the resource spending side, the picture is much as you would expect from the principles of the Barnett formula. Scotland’s Block grant started the period around £1,430 larger than the funding for comparable UK Government departments, and that difference is almost exactly preserved in cash terms. That is what the Barnett formula is designed to do – take the cash differences in spending to begin with and provide a similar addition in funds per person as that for UK Government departments.

Chart 1: Real-terms resource funding per person in the Scottish Block Grant and comparable UK Government departments

Source: HM Treasury, ONS, National Records of Scotland, FAI analysis

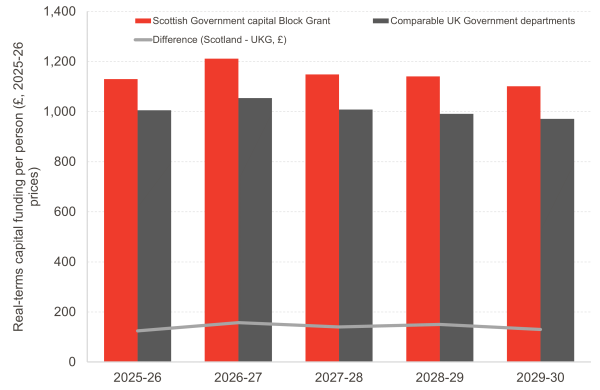

The picture is similar on capital, with a little more movement due to the timing of projected population changes interacting with the profile of capital spending and the fact that static population shares are used for the SR period.

Chart 2: Real-terms resource funding per person in the Scottish block grant and comparable UK Government departments

Source: HM Treasury, ONS, National Records of Scotland, FAI analysis

Looking at this, you’d be hard pressed to say that Scotland has been treated any differently than UK Government departments with comparable responsibilities, save for the fact that its funding remains higher by around £1,500 per person across resource and capital.

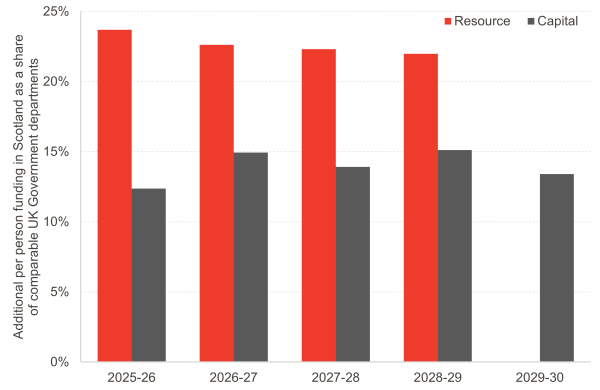

Over time – all else equal – we would expect the percentage difference between the per person levels of the Scottish Block Grant and equivalent UK Government departments to shrink, a process known as ‘Barnett convergence.’ Again, this is by design of the formula, and happens very gradually if at all – it has barely changed since the early 1990s apart from small movements, largely because population growth in England has been much faster than in Scotland.

Chart 3: Additional per person funding in Scotland as a share of comparable UK Government departments

Source: HM Treasury, ONS, National Records of Scotland, FAI analysis

There is a bit of forecast Barnett convergence throughout the SR period, though not that significant. As chart 3 shows, resource funding in the Scottish Block Grant will be 22% higher than funding for UK Government departments with comparable responsibilities; the respective figure for capital funding is 13%.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.