Alongside this month’s Budget, the Scottish Fiscal Commission will set out forecasts for VAT revenues in Scotland.

2019-20 will mark the first year in which VAT assignment will be explicitly incorporated into the Budget (although, as with all the phased implementations of Scotland’s new tax powers it will be 2020-21 before it has a meaningful implication for spending).

In this blog we remind readers of the background to VAT assignment, discuss the approach that has been put forward for implementation and outline some implications for the Scottish Budget.

Working out how much VAT is raised in Scotland is exceptionally difficult. Unfortunately, a paper published recently by the UK Government on how it plans to do this suggests that little progress has been made in finding a robust way forward after over 3 years of trying.

Given the sums involved, the Scottish Parliament would be taking on a significant – and unreasonable – risk based upon current plans. It should, at the very least, press for a delay in the assignation of VAT to the Scottish Budget.

Background

VAT assignment was first proposed by the Smith Commission in 2014. The idea was to assign essentially half of VAT receipts to the Scottish Budget.[1]

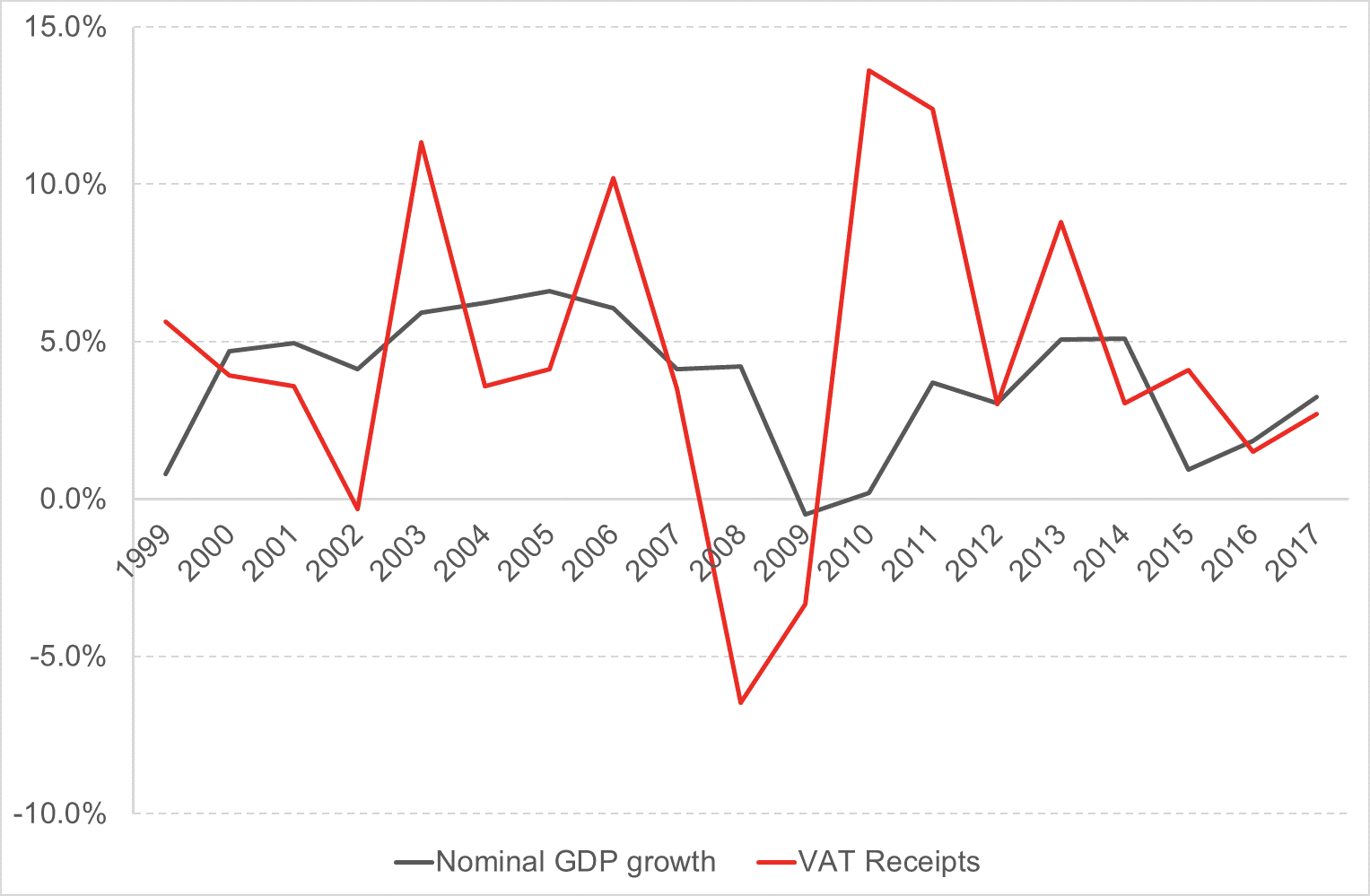

The motivation behind this idea was to open up an increased portion of the budget to the performance of the Scottish economy. Using estimates from GERS and Scottish GDP data, we can see that estimated VAT receipts track economic performance reasonably well, although the volatility in the estimate is clearly apparent. The large divergences that do emerge largely reflect policy changes (e.g. the cut to 15% in 2008 and the rise to 20% in 2011, for example).

Chart 1: Scottish Nominal GDP Growth and VAT receipts

Source: Scottish Government

Whether it is a good idea to open up the Scottish Budget to such levels of economic volatility is of course a matter of opinion. However, what is clear is that assignation of VAT is crucial to ensuring that the percentage of devolved spending funded by ‘Scottish taxes’ will rise to around 50% – something that has been used by some to label the Scottish Parliament “one of the most powerful devolved parliaments in the World”.

Estimating VAT receipts in Scotland – Previous Approaches

There is one big challenge with assigning or devolving VAT to Scotland. Businesses are not required to report separate VAT returns for sales made in Scotland. Unlike income tax, which is based upon where a worker resides, VAT is much more complex to identify. Whilst in theory, it could be possible to ask businesses to provide separate VAT returns for activities in Scotland vis-à-vis the rest of the UK, the potential cost and burden on business would be large.

So without actual VAT receipts, in the past, both the Scottish Government and HMRC have used different techniques to provide an ‘estimate’ of VAT receipts in Scotland.

How do they do this?

At the UK level, the VAT Theoretical Tax Liability (VTTL) model works out the theoretical VAT liability in the UK as a whole (as the name suggests!). This is then compared to actual receipts, to work out the “VAT gap” for the UK (i.e. it gives HMRC an idea of VAT going uncollected).

Previous approaches have looked to regionalise this model to come up with a Scottish share for VAT. This has been done by using the Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS) to produce estimates of the expenditure on different goods in Scotland (and rUK). An assumption is then made that the VAT gap is proportionately the same across the UK.

In some instances, other methods are used – e.g. for government and the exempt sectors – but the majority of revenues estimated hinge on the LCFS data.

But there are a number of issues with this approach.

Chief amongst them is the robustness of the underlying statistics.

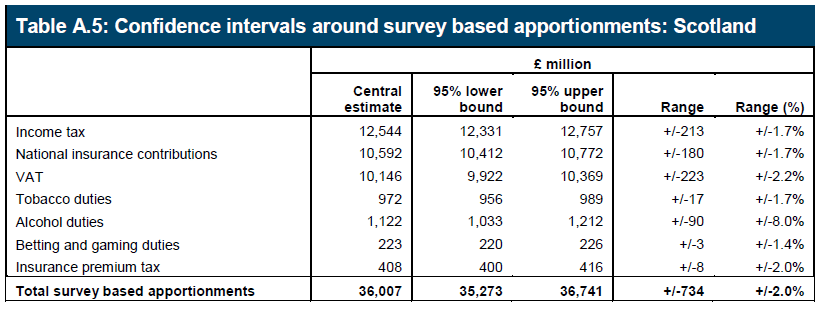

The LCFS has a small sample size[2]: prior to 2017-18, it was only 500 households per year. This means that the confidence intervals are significant – see Table 1 from GERS which shows that for 2017/18 the confidence interval was plus/minus £223m. In other words, we can be 95% confident that the ‘true’ value for VAT revenues in Scotland could lie anywhere between £9.9bn and £10.4bn.

Table 1: Uncertainty around survey based estimates

Source: Scottish Government

These are obviously significant fluctuations – arguably acceptable when the purpose is a statistical publication of Scotland’s overall public finances, but much less so when it comes to marginal changes in day-to-day Scottish budget lines.

Estimating VAT receipts in Scotland – the new approach

Recognising that earlier estimates were weak in the context of the new tax powers, both governments started working on a better way to assigning such receipts to Scotland. Presumably, many approaches have been examined.

One option is to boost the sample size underpinning LCFS. Indeed this has already happened. However, although the survey size has now doubled, this is still a very small sample for work of this kind. In their paper published in September, the SFC said

Household expenditure accounts for the majority of VAT revenue assigned to Scotland. Any approach to assigning household expenditure liable to VAT to Scotland would rely heavily on the LCF to estimate the proportion of UK expenditure occurring within Scotland. Despite the boost to the survey sample from 2017-18 it is likely that this estimate will have a large confidence interval. This variability will affect both the baseline for our forecast and our forecast evaluation.

The second approach – presumably – would be to have explored the use of administrative data. But this is fraught with difficulty. As highlighted above, companies only report VAT at a UK level and asking them to separate out their ‘Scottish-activities’ is likely to hit a number of practical issues such as inter-company payments and reclaims.

So what have the governments come up with?

The paper published last week settles upon an approach that – at least at first glance – appears very similar to the previous approach for estimating Scottish VAT receipts.

This raises a number of concerns.

Firstly, one issue that should be of particular concern to MSPs is that the paper is scant on detail. Indeed, the document doesn’t even include any estimates of past-VAT revenues in Scotland, making it impossible to scrutinise the methods or examine differences to previous attempts. We can only hope that this is remedied around the time of the Scottish Budget.

Secondly, based upon the data that has been published, the methods don’t seem to offer much in the way of a substantial improvement – or narrowing of the ‘margin for error’ of hundreds of millions of pounds in the current GERS estimates.

The method essentially takes the sectors as set out by the VTTL, and regionalises them using various indicators. This includes the LCFS, but they have now added in various earnings, business activity and construction industry data. But the paper is not clear about which and how survey indicators will be used.

Why does this matter?

This may seem like a dry statistical issue. But this margin for error matters as it gives the range within which we can have confidence that the ‘actual’ value lies within. We have seen the issues with the Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI) data that have been used for income tax, and this is a large sample of tax payers.

At least with income tax we will get administrative final outturn data. As we have already set out, this will never be the case for VAT.

As a result, the Scottish VAT series has the potential to fluctuate significantly from year to year – not because of changes in Scottish economic performance – but simply because of changes in the underlying dataset used by statisticians. With potential fluctuations of tens of millions of pounds (if not more), simply from statistical measurement uncertainty, this poses a risk to the Scottish Budget.

Conclusion

The amount of detail published on VAT assignment leaves a lot of questions unanswered. But from what we can tell, the method appears similar to previous approaches. This should cause concern for Scottish Ministers and MSPs. Given the reliance on survey based estimates, this has the potential to introduce significant fluctuations into the amount of VAT assigned year-on year, and therefore potentially into the Scottish Budget.

A key aim of the Smith Commission was to improve accountability and make Scotland’s politicians responsible for the money that they spent. Unfortunately rather than helping to deliver this aim, the current proposals for VAT assignment risk undermining that principle.

Perhaps it is wise to pause and think again.

[1]We say essentially here, because actually it is the first 10p of the standard rate (at 20p) and the first 2.5p of the reduced rate (at 5p). Therefore, if the UK rate was to change the proportion of the VAT receipts raised in Scotland that would be assigned would also change.

[2] There are other issues which have got worse in recent years, such as the response rate, which is now around 50%: this potentially reduces the power of the survey.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.