Introduction

That 2020 has been a year without precedent scarcely needs saying. The unprecedented nature of 2020 is no more obvious than when it comes to the public finances – and the Scottish Government’s budget is no exception.

The Scottish Budget will receive over £8bn in additional spending consequentials in 2020/21 than was anticipated when the budget was agreed in February.

In the context of a block grant at the start of the year of £30bn, that is clearly a substantial increase. It represents almost £1,500 of additional spending per capita.

The pace at which new funding has been allocated and new policies have been announced means that keeping track of how the additional funding has been allocated in Scotland is not always easy. Over £2bn of consequentials remain to be formally allocated (although significantly less than this remains uncommitted).

What we do know is that over £2.4bn additional funding has been allocated to health. Business support comes in the form of over £1.5bn worth of grant support, in addition to £900m of business rates reliefs. Transport operators have received over £350m of support. A plethora of policies have been targeted at households most at need of financial support, with funding totalling over £400m. And new funding has been made available to support further and higher education and develop new training and employability initiatives.

The Scottish Government will soon begin turning its thoughts to its budget for 2021/22 – Finance Minister Kate Forbes is due to present her tax and spending plans to parliament on 28th January.

The UK Government’s spending plans for 2021/22 – which will be laid out by Rishi Sunak on Wednesday – provide critical context for that planning. The plans laid out by the Chancellor will determine the size of the Scottish block grant, and the broad envelope that the Scottish Government will have to work with (even with significant tax devolution, the block grant remains critically important in determining the overall size of the spending envelope available to the Scottish Government).

Of critical importance here will be the extent to which Covid-related funding changes announced during 2020/21 – particularly around the NHS and business support measures – will be baked-in to departmental settlements, or will be unwound in the expectation of the beginnings of recovery.

To provide some context, this article summarises the ways in which the Scottish Budget has evolved since March 2020, and some of the fiscal issues that have emerged.

Over £8 billion of additional consequentials will flow to the Scottish Budget during 2020/21 to mitigate the effects of Covid

The Scottish Budget 2020/21, as approved by parliament in February, set out plans for resource spending of almost £35bn, underpinned by a core block grant from the UK Government of £30bn. At the time, Covid was not perceived as a significant economic risk.

By the time of the UK Budget on 11 March, Rishi Sunak opened his budget statement by saying that Covid was ‘the issue most on everyone’s mind’. He outlined the UK Government’s initial measures to mitigate what he described as the virus’ ‘temporary’ but ‘significant’ impact on public health and the economy. These measures included additional funding for the NHS in England, and business rates relief for businesses in the retail and hospitality sectors in England.

These announcements, and others, generated additional consequentials for the Scottish Budget. Over the course of the next few weeks, additional UK Government announcements on a seemingly weekly basis added further to the consequential amounts.

By mid-April, £3.5 billion of additional resource consequentials had been allocated to the Scottish Budget as a result of UK Government Covid-related spending in England. This figure had increased to £4.6bn by the time of the UK Government’s Summer Economic Update on 8 July.

Up until this point, the UK Government had determined increases to the Scottish block grant by applying the Barnett Formula in the usual way. UK Government announcements of spending increases in England generated consequential increases in the Scottish block grant.

But the problem with relying on the Barnett Formula during a time of fast-moving crisis was that it resulted in lags between the UK Government announcing a policy for England, and the devolved governments being able to design and announce their own schemes – which they could only do once they had learnt of the consequentials arising from the UK Government policy.

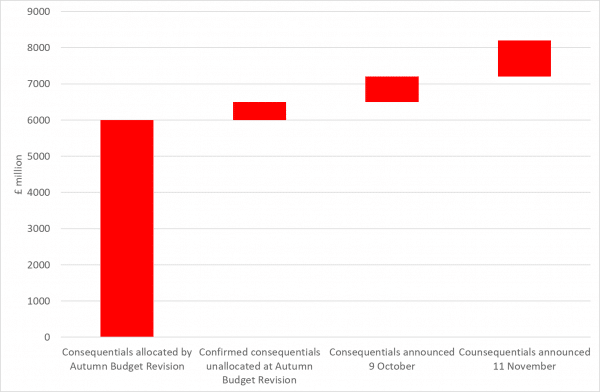

In response to this, the Treasury moved to a system of guaranteed funding for the three devolved governments. On 24 July, the Scottish Government was notified that it would be guaranteed a minimum £6.5bn uplift in consequentials during 2020/21. This was an upfront guarantee of funding that provided £800m of additional resources over and above the uplift in the Scottish block grant that would have been identified at that point in time had Barnett been applied in the normal way.

In principle this meant that the Scottish Government did not need to wait for the UK Government to make policy announcements for England before it decided how and when to provide support in Scotland.

The guaranteed amount was increased to £7.2bn on 9 October and then to £8.2bn on 11 November[1].

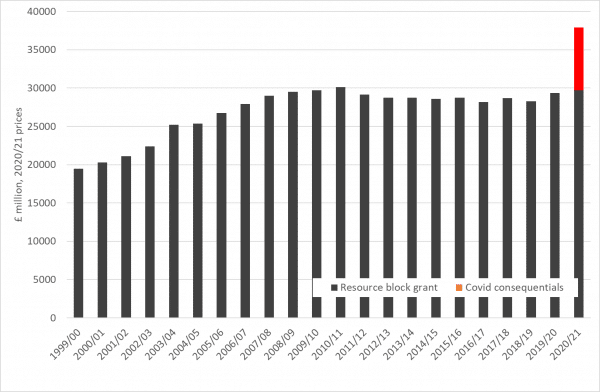

The scale of this increase in block grant allocation is unprecedented (Chart 1). To put it in some context, the resource block grant at the time of the 20/21 budget was around £29.7bn. Whilst not all of the £8.2bn consequentials will translate into additional spending (as discussed below, around £900m will offset additional business rates reliefs), a spending increase of £7bn would equate to 23% higher spending than was anticipated at the time of the budget.

Chart 1: £8.2bn of Covid-consequentials in context

Scottish Government resource block grant at successive budgets, plus Covid-related consequentials during 2020/21

The Scottish Government had allocated £6bn of the £6.5bn of Covid-related consequentials available to it by September

The Scottish Government published its Autumn Budget Revisions on 24 September, two months to the day after it had received notification that it would receive a guaranteed £6.5bn in resource consequentials for 2020/21.

The Autumn Budget Revision (together with the exceptional Summer Budget Revision that had been published in May) set out how £6bn of that £6.5bn would be allocated, leaving (at the time) just over £500m to be allocated.

How was the Scottish Government’s Covid-19 spending allocated? One way to analyse that question is to break the spending down into broad areas of support: health, business support, financial support to those on low-incomes and other vulnerable groups, support to transport providers, and education and training.

Health

Around £2.4bn had been allocated to the health portfolio to cover costs associated with staffing, PPE procurement and setting up and running test and trace services at the time of the Autumn Budget Revision. Health’s share of the £8.2bn of additional consequentials is likely to end up notably higher than this.

Business support: £900m to offset rates reliefs, plus over £1.5bn in grants

Support for businesses suffering reduced demand comes in two forms: reductions in business rates, and a plethora of grant-funding schemes.

In terms of business rates, some £900m has been allocated to local authorities to offset revenue losses from the extension of Non-Domestic Rates reliefs (amounting to full relief for retail, hospitality and tourism businesses, and 1.6% relief for all other properties).

The Scottish Government’s initial business grant scheme allocated to £1.3bn to local authorities to provide business grants to business in receipt of the small business bonus and businesses in retail, hospitality and tourism. By early September, just over £1bn had been awarded to business through these schemes[2].

This was supplemented by a Pivotal Enterprises Resilience Fund which has been allocated £120m[3], and £34m of support for the newly self-employed who are not covered by the UK Government’s Self-Employment Income Support Scheme.

A range of more sector-specific business support has also been provided, including £30m to support lost revenues for cultural venues (Creative, Tourism & Hospitality Enterprises Hardship Fund)[4], and £37m for Historic Environment Scotland. There have also been support packages announced for fisheries and aquaculture, grants for larger hotels (£14m) and self-catering businesses (£1m) a £62m Energy Transition Fund[5] for the energy sector (the latter is partially justified in relation to Covid).

Communities and those at risk of financial distress

A large part of the support for households at risk of financial distress has been channelled through the £350m Communities Fund which was announced at the start of the pandemic[6]. This included several funds allocated to local authorities to address financial hardship (the Scottish Welfare Fund and hardship fund) and food insecurity (Food Fund), as well as £75m to support charity and third sector organisations who support at-risk and vulnerable groups. It also included £50m for local authorities to offset increases in Council Tax Reduction payments.

Outwith the Communities Fund, support for individuals includes the Carer’s Allowance Supplement (costed at £19m[7]), funding for Free School Meals during holidays (£40m). A range of smaller interventions have also been announced, including support for tenants and financial support to help households in financial difficulty – although it is not always clear to what extent some of these smaller interventions are subsets of broader initiatives, or represent new funding in their own right. Additionally, local authorities received £150m to offset reduced fees and charges income.

Transport

The transport portfolio has been allocated £360m to support rail (£300m), bus (£110m) and ferry (£35m) services, with some offsetting savings from elsewhere within the portfolio.

Education, skills and training

Additional funding for the education and skills portfolio includes £100m for additional teacher training and to address attainment inequalities; £75m to support university research; funding to colleges and universities to support estate maintenance and digital inclusions (£15m); and smaller amounts to support Youth Services, community learning services and to students.

An additional £100m has been allocated to support employability and training interventions, focussed in particular on supporting employment opportunities for the young through the Youth Jobs Guarantee[8].

The funding interventions outlined above total just over £6bn.

But keeping an accurate tally on the Scottish Government’s Covid-19 interventions is tricky given the fast-moving nature of the crisis, and the level of information provided

However, it is difficult to keep track of the Scottish Government’s Covid-19 spending. In part this reflects the sheer number of policy announcements that the Scottish Government has made, reflecting the fast-moving nature of the crisis and the regularly evolving status of its budget. According to Audit Scotland, the Scottish Government had made over 90 Covid-19 related spending announcements by the end of July[9].

But these announcements do not always relate to ‘new’ funding – sometimes an announcement is made when a fund is launched, with subsequent announcements when a specific element of that funding strand formally opens for applications, or when new funding is added.

In principle, the budget revisions in May and September should provide the mechanism through which some clarity is brought to the totality of Covid spending activities. However, whilst the budget revisions show in broad terms how allocations to different portfolios have changed, they often provide funding information at a more aggregated level than is made in government policy announcements; they also conflate Covid and non- Covid spending changes, and new funding with transfers of existing funding between portfolios. It can therefore be tricky to match up spending changes with specific policies.

For example, the Scottish Government announced a £230m ‘Return to work’ package of support in June[10]. The policy includes support to businesses and digitisation in justice and education, implying that the funding will cut across several portfolios. But only £50m of spending in the Autumn Budget Revision is explicitly badged as being part of the Return to Work programme.

In the preceding analysis we have tried to reflect as accurately as possible the totality of Covid-related spending, drawing on a range of published sources. But it is possible that some interventions are not included in the totals above; whilst some may be double-counted.

Whilst the pandemic has created an unprecedently challenging policy environment, it is unfortunate that the Scottish Government has not yet provided a comprehensive overview of the totality of its Covid funding commitments. For the purposes of transparency and scrutiny, it is imperative that the Scottish Government provides a more comprehensive analysis than it has so far been able to. This will be the first stage to understanding, in due course, the effectiveness and impact of the interventions delivered.

LBTT reliefs are likely to be more than offset by increased resources stemming from Stamp Duty changes in England

In addition to the changes resulting from increased Barnett consequentials, the Scottish Government has also made two changes to Land and Buildings Transactions Tax (LBTT) since March. It extended the length of time during which buyers can claim back the Additional Dwelling Supplement (i.e. where a buyer purchasers a second property, then have longer to sell their first property and be eligible to reclaim the supplement). It also increased the nil rate of LBTT from £145,000 to £250,000.

These two policies are forecast to cost £37m in combination[11].

The UK Government has announced similar measures in England. This results in a reduction in the ‘block grant adjustment’ – the amount that is deducted from the Scottish block grant.

The SFC notes that the reduction in Scotland’s block grant adjustment for LBTT is likely to more than offset the loss of revenues from the Scottish tax policy change[12]. This is because the policy in England is forecast to lead to a proportionately larger reduction in English revenues compared to the reduction in Scottish revenues.

This is a complicated way of saying that, because the Scottish policy is somewhat less generous than the equivalent English policy (in England, the nil rate band is extended to £500,000), the costs of the Scottish tax policy are more than offset by increases in the Scottish block grant.

The Scottish Budget is largely protected from Covid-related falls in devolved revenues

The Scottish budget 2020/21 was underpinned by forecasts of tax revenues – including £12.4bn from income tax and £640m from LBTT.

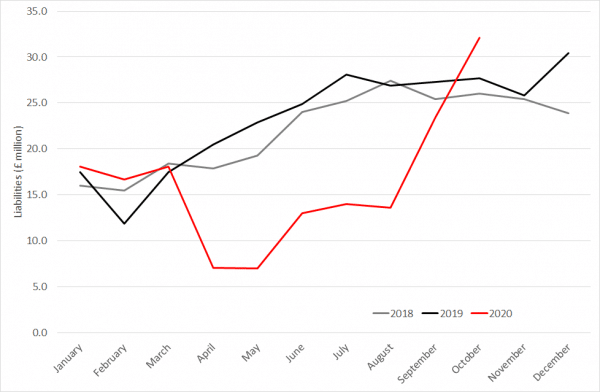

Revenues from both taxes will almost certainly come in lower than forecast (Chart 2 for example shows a clear impact of the crisis on LBTT revenues between April and October this year relative to previous years).

But under the Scottish fiscal framework, the Scottish Budget is largely protected from these revenue falls. As long as the revenue falls in Scotland are proportionate to the equivalent revenues in rUK, the Scottish Budget will be no worse off. The Scottish Budget is only liable for the impact of proportionately greater revenue declines in Scotland – to date there is no strong evidence to suggest that economic impacts of the crisis have been disproportionately felt in Scotland, but this remains an ongoing source of risk.

Similarly, the Scottish Budget is largely protected from the risk that spending on devolved social security payments in Scotland ends up higher than forecast – the risk to the budget is that Scottish spending on social security increases disproportionately quickly in Scotland than rUK, relative to initial forecasts.

Data published as part of Wednesday’s Spending Review will include interim data – for the first six months of the 2020/21 financial year – on outturn spending on devolved social security in Scotland relative to rUK, and LBTT and Landfill Tax revenues in Scotland relative to equivalent rUK taxes. This will give the first indication of the extent to which there have been any significant assymetric fiscal impacts of the crisis that the Scottish budget might be liable for.

Chart 2: Revenues from residential LBTT are over £60m lower in 2020/21 than we might expect in a ‘normal’ year

LBTT residential tax liabilities (excluding Additional Dwelling Supplement) per month, 2018-2020

Substantial resources for 2020/21 remain unallocated… but a lack of transparency means the exact level of unallocated resources is unclear

The Autumn Budget Revision set out how £6bn of Covid-related consequentials are formally allocated, leaving £500m formally unallocated. In delivering the ABR, Kate Forbes insisted that whilst this £500m was formally unallocated, it was ‘committed’:

“This leaves just over £500 million of COVID-19 resource consequentials formally unallocated, but I can remind opposition members who appear to be confused about the nature of a budget revision, that this funding is fully committed to the COVID-19 response. It will be formally allocated through the spring budget revision – a budget revision is a retrospective, budget process[13].”

We now know that the Scottish Government will receive a guaranteed minimum of £8.2bn of Covid-related consequentials for the 2020/21 year.

It is clear from policy announcements that a number of additional funding allocations have indeed been made since the Autumn Budget Revision was published. These announcements include additional business grant funding, additional support for local authorities of £140m, adult social care (£112m) the self-isolation support grant, support for children and young people’s mental health services, and a student Covid-testing scheme.

Some of these announcements have been associated with explicit funding amounts, others have not. However, it is increasingly difficult to know to what extent these funding announcements are additional to previous announcements or not – and the extent to which more recent business grant allocations are recycling unused funds from previous schemes.

Taking recent announcements into account, it seems possible that around £1bn of funding for the 2020/21 financial year remains uncommitted at this point – but there is significant uncertainty around the size of this number.

The Scottish Government has indicated that it does not intend to publish any comprehensive analysis of its funding allocations over the remaining course of the year until the Spring Budget Revision in February. This may therefore appear after the budget for 21/22 has been presented – which may complicate scrutiny of the 21/22 spending plans.

In principle the Scottish Government does not have to allocate the entirety of its £8.2bn consequentials for spending in 2020/21 – up to £700m can be placed in the Scotland Reserve and drawn down in future years. However, under current rules only £250m can be drawn down from the Reserve in any single year, and thus the scope for transferring significant sums from 2020/21 in 2021/22 is quite limited. The Scottish Government may seek greater flexibilities from HM Treasury in how the Reserve can be used.

Chart 3: Over £2bn of confirmed consequentials will not be formally allocated until the Spring Budget Revision – but an unknown proportion of these have been ‘committed’

Breakdown of the £8.2bn of consequentials by date confirmed, and allocation status

Guaranteed funding brings constraints, but these are outweighed by the benefits

The move towards guaranteed funding brings both benefits and potential challenges. The obvious benefit to the Scottish Government is the relative certainty of funding in coming months.

But the breaking of the link between consequentials and specific UK Government policies brings both challenges and opportunities.

As pointed out by SPICe[14], the challenge is that it becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible, to know whether the Scottish Government is fulfilling commitments to ‘pass on’ health related consequentials to the health budget, or local government consequentials to the local government budget. The Scottish Government knows what minimum level of budget uplift it will receive, but not the source of that uplift in terms of specific UK Government announcements.

But this challenge is also an opportunity. When consequentials are linked explicitly to particular UK funding policies, the Scottish Government tends to come under significant pressure to follow the pattern of spending very closely. The move to guaranteed consequentials in principle should provide the Scottish Government greater flexibility to allocate funding in the ways it deems most appropriate for Scotland, unencumbered by demands for precise parity.

Request for additional fiscal flexibilities denied; but greater funding certainty is a real boon

The pandemic has exposed some strengths of the existing fiscal settlement but also revealed some weaknesses.

The strengths are that spending by the UK Government on ‘devolved’ services in England automatically generate funding increases for the Scottish Government; and that the Scottish Budget is protected from major falls in revenues from devolved taxation.

But in the initial phases of the crisis, some weaknesses of the existing system were exposed. In normal times, a lag of several days or even weeks between a UK Government policy announcement and the notification of consequentials for the Scottish Budget would not be problematic. But in the case of a fast-moving health and economic crisis, short lags could cause important delays in the Scottish Government being able to plan and announce its own measures.

The problem of lags was accentuated by changes in the estimate of consequentials associated with some UK Government spending announcements – so that the Scottish Government would receive notification of consequentials, commit funding to a policy, and then find out that the estimate of consequentials had been revised downwards, creating pressure on the Scottish Budget.

In response to these issues, Kate Forbes wrote to the Treasury in May requesting greater certainty over Barnett consequentials, and some additional budget flexibilities to manage budget uncertainty[15].

This letter was followed up by a subsequent letter from Ms Forbes in June which included specific requests in relation to fiscal flexibilities. The flexibilities sought included:

The temporary ability during 2020/21 to transfer up to £500m of capital budget to resource; and

To be able to use its existing £500m borrowing limit for ‘cash management’ to fund discretionary resource spending increases[16].

Together, these two flexibilities would give the Scottish Government the scope to boost its budget by £1bn in 2020/21.

The UK Government has never formally responded to the request for additional fiscal flexibilities – a clear indication of its opposition to the proposals. In some ways, the UK Government’s denial of these flexibilities seems unreasonable – the Scottish Government’s request was not for additional funding, but for flexibility in how it used its existing capital budget allocation and existing borrowing tools.

The denial may well simply reflect the Treasury’s well-established inclination to demonstrate its position of fiscal authority in dealings with government departments in general, rather than any particular antipathy towards the Scottish Government. But whether the denial of requests for some fairly basic fiscal flexibilities – from a government with substantial policy autonomy – is the appropriate response will remain a subject for debate.

Nonetheless, the commitment by the Treasury to the concept of funding guarantees represents a significant concession, and removes one of the main – perhaps the main concern – raised by the Scottish Government in the early part of the pandemic. In fact, this flexibility somewhat (if not completely) undermines the perception of HM Treasury as being completely insensitive to the funding needs of the devolved government.

Another issue of potential concern raised by the Scottish Government in the early part of the crisis (and raised by the IFS), was the risk that funding needs in Scotland (or any other devolved territory) turned out to be higher or more severe than in England – to the extent that Barnett consequentials could be characterised as inadequate.

The Treasury was always likely to want to ignore the issue until it became a reality – and to the extent that neither the health nor the economic impacts of the virus have disproportionately affected any of the devolved territories in a very obvious way, this issue has remained on the sidelines.

Ironically the issue of territorial funding created perhaps more friction within England than it did between the UK and devolved governments. And the question of whether a furlough scheme that was available in England under a given set of restrictions would or would not be available in Scotland if equivalent restrictions applied briefly threatened to become a major constitutional crisis before the UK Government decided that blanket provision was preferable.

For the time being, intergovernmental disputes around funding remain fairly low-key and somewhat technocratic. But underlying tensions could potentially see funding disputes escalate rapidly.

The UK Spending Review

Against this backdrop, Rishi Sunak will present the UK Government’s Spending Review on Wednesday. This will be a one-year Spending Review, although it is anticipated that it will set multi-year funding settlements for some departments.

From the perspective of the Scottish Budget, the primary interest of the Spending Review will be to understand the size of the Scottish block grant in 2021/22, for both resource and capital spending.

On capital spending, the Scottish block grant increased by around 12% in 20/21 compared to 19/20 – that was nothing to do with Covid, but the result of the UK Government’s proposed ‘infrastructure revolution’. Assuming the UK Government sticks to the broad scale of ambition for infrastructure investment articulated in its March budget, the Scottish block grant for capital is likely to see another substantial increase in 2021/22. The increase is unlikely to be as high as last year, but might not be too far off.

On resource spending, the big question is how much of the exceptional Covid-related spending announced during 2020/21 will continue in 2021/22. Although there is good news on the horizon in relation to vaccines and improved testing, it seems inevitable that whilst some Covid-related spending can be pared back, there will be an ongoing need for Covid-related spending in many areas. The question of when various forms of support can be withdrawn – for example the business rates reliefs to tourism and hospitality businesses – will also be a difficult judgement to make, and one that will have funding implications for the Scottish Government.

Of course there is no way at this stage that Rishi Sunak can know for sure how much Covid-related spending might need to persist into 2021/22. The public finances will need to continue to respond flexibly to the pandemic. The need for additional spending might arise during the year in some areas; whilst in other areas it may be possible to withdraw Covid-related funding more rapidly than anticipated.

Rishi Sunak is likely to emphasise the need for flexibility in delivering his Spending Review. But he will need to ensure that flexibility in the UK Government’s response does not translate into budget uncertainty for the devolved governments.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-extends-furlough-to-march-and-increases-self-employed-support

[2] https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-business-support-fund-grant-statistics/

[3] https://www.gov.scot/news/help-for-businesses-1/

[4] https://www.gov.scot/news/help-for-businesses-1/

[5] https://www.gov.scot/news/gbp-62-million-fund-for-energy-sector/

[6] https://www.gov.scot/publications/supporting-communities-funding-statement/

[7] https://www.fiscalcommission.scot/forecast/supplementary-costing-may-2020/

[8] https://www.gov.scot/news/gbp-100-million-for-employment-support-and-training/

[9] Audit Scotland (2020) Covid-19: implications for public finances in Scotland. https://www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/uploads/docs/report/2020/briefing_200820_covid.pdf

[10] https://www.gov.scot/news/return-to-work-package-launched/

[11] https://www.fiscalcommission.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Publication-Fiscal-Update-September-2020.pdf

[12] https://www.fiscalcommission.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Publication-Fiscal-Update-September-2020.pdf

[13] https://news.gov.scot/speeches-and-briefings/statement-on-the-autumn-budget-revision-29-september-2020

[14] https://spice-spotlight.scot/2020/11/12/covid-19-barnett-consequentials-guarantee-up-again-more-certainty-less-clarity/

[15] https://news.gov.scot/news/covid-funding-plea#downloads

[16] The Scottish Government has the ability to borrow up to £500m to address temporary shortages in cash that may in theory arise given the uneven nature throughout the year of certain types of spending. However, the requirement to borrow for this specific purpose is unlikely to ever be required, given the Scottish Government’s existing cash authorisation limits.

Authors

David Eiser

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute