Tax has been at the forefront of policy debate throughout this parliament. Most noticeably have been the Scottish Parliament’s new powers on income tax. These became operational in 2017, and paved the way for significant policy divergence to open up between Scotland and the rest of the UK (rUK).

But there have been significant policy changes in other areas too. Council tax has been subject to its first substantive reform since the parliament was established in 1999, and there has been a resounding break with the council tax freeze policy that applied during the nine years prior to this parliament (before it was reapplied in 2021). A major review of Non-Domestic Rates has ushered in several changes to business rates. And the Scottish Government has continued to carve a distinctive policy on aspects of property transactions taxes.

A new paper out today examines the tax policy choices that have been taken in the 2016-2021 session of parliament (covering the five budgets from 2017/18 – 2021/22). It considers the rationale for the policies, and their impacts on taxpayers and government revenues.

The common thread linking tax policy decisions

The key thread linking tax policy decisions this parliament is the Scottish Government’s aspiration to be able to make two points about its tax policy.

- First, that a large proportion – if not the majority – of Scottish taxpayers pay less tax than they would under the rUK policy.

- Second, that Scottish tax policy is more progressive than the policy that prevails in rUK. This often means that taxpayers towards the top of the distribution (by income or property value) face higher tax liabilities than under the rUK system – sometimes substantially so.

This theme is common to all major devolved taxes, including income tax, council tax, property transactions taxes, and business rates. The Scottish Government argues that the resulting tax system is ‘fairer’ and ‘more competitive’ than the rUK system.

Income tax: a progressive approach to revenue raising

The approach has been most explicitly set out in the case of income tax. The Scottish five-band rate system, combined with a lower threshold for the higher rate than in rUK, is forecast to raise around £500m additional revenue to support public services spending in Scotland, compared to if the UK Government policy were applied.

However, the lowest-income half of Scottish income taxpayers pay slightly less income tax than they would if they were liable for rUK rates. The additional revenue is raised by subjecting taxpayers in the top half of the income distribution to somewhat larger tax rates than they would face in rUK.

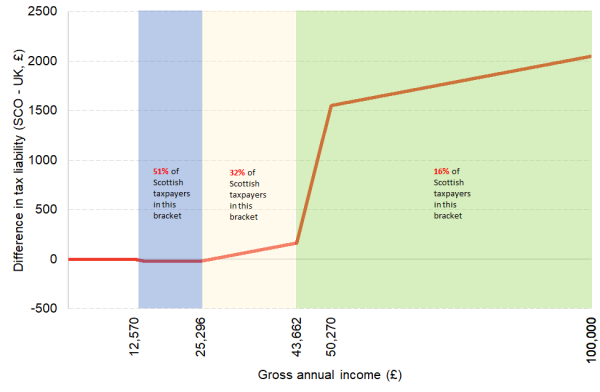

The difference is particularly marked for the 16% of Scottish income taxpayers whose incomes exceed the Scottish higher rate threshold of £43,667. As a percentage of income, the difference peaks just above £50,000. Scottish taxpayers face £1,550 more in liabilities than they would if rUK rates prevailed (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Difference in annual income tax liability, Scotland v. rUK 2021/22

Source: Analysis of Scottish Government data

Land and Buildings Transactions Tax: a bit less for some, much more for a few

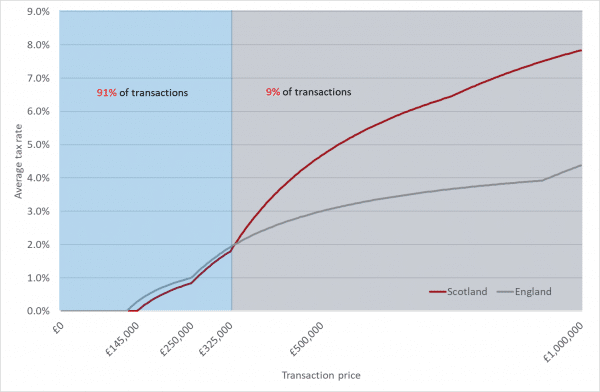

When it comes to Land and Buildings Transactions Tax, residential tax rates are set so that 90% of property transactions in Scotland pay less than they would if subject to rates in England/NI. But the top ten per cent of residential property transactions by value pay more tax than they would if subject to English rates – sometimes by a substantial margin (Chart 2).

Overall, the Scottish policy is anticipated to be revenue raising, despite 90% of Scottish properties facing lower liabilities than they would in England.

On non-residential LBTT, Scottish rates are set slightly below those prevailing in England for most values of transactions, with no off-setting higher liability in Scotland.

Chart 2: Average residential property transaction tax rate, Scotland and England (2021/22)

Business rates: the UK’s most competitive?

The Scottish Government argues that Scotland has the ‘most competitive’ system of business rates in the UK. There are two parts to this claim. First, a slightly more generous set of reliefs for businesses occupying low-value premises (the so-called Small Business Bonus) than prevails in England. And second, a slightly lower headline rate, or poundage. The result is that 95% of businesses are liable to lower business rates in 2021/22 than they would be in England – although the difference is marginal for the majority of these businesses.

And, consistent with its approach to taxation generally, businesses occupying the highest value premises in Scotland do pay a small premium (again, very marginal) on their rates compared to equivalent businesses in rUK.

Council tax: lower but more progressive than England/Wales

The 2017/18 budget at the start of this parliament marked the end of the nine year council tax freeze. Typical band D council tax rates have increased by more than inflation this parliament – but they remain well below those in England and Wales, a legacy of the prolonged freeze.

In 2017/18 the Scottish Government reformed the ratios between council tax bands, so that higher banded properties (in bands E-H) pay relatively more tax than those in bands A-D than was previously the case.

So the story on council tax is that rates are lower than in rUK but the system is more progressive with respect to (out-of-date) property band.

A different burden of personal taxation

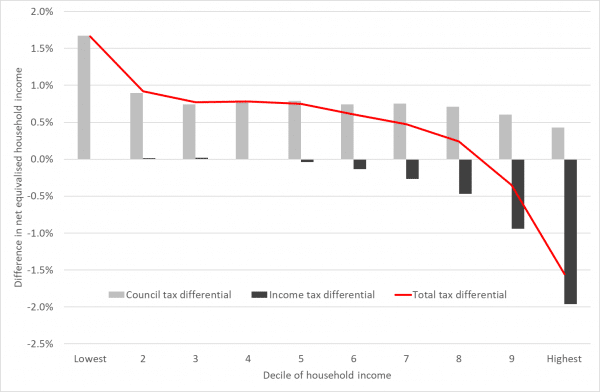

This parliament has seen an at times fractious debate about whether Scotland is the highest or lowest taxed part of the UK. Taking the two major personal taxes in combination – income tax and council tax – the picture is somewhat nuanced.

Scottish income tax policy is revenue raising compared to that in rUK, raising around £500m in 2021/22, mainly from the highest income 16% of income taxpayers.

But council tax bills are significantly lower in Scotland than in England or Wales, largely as a legacy of the nine-year freeze. Typical band D rates in Scotland are £400 less than in Wales and £600 less than in England. Good news for household budgets, but less good for the budgets of Scottish Government and local authorities. In fact, lower council tax rates in Scotland cost the Scottish budget over £500m in revenue, compared to policy in rUK – even after accounting for the change to council tax ratios in Scotland.

Personal tax policy in Scotland relative to rUK is therefore best characterised as transferring liability from council taxpayers to (higher income) income taxpayers. Chart 3 shows the distributional effects. Lower council tax rates in Scotland raise net incomes in Scotland in all parts of the distribution – although the impact is less towards the top of the distribution, given the council tax ratio reforms introduced in Scotland in 2017/18. Differential income tax policy reduces net incomes at the top of the distribution in Scotland, relative to the case where rUK policy was implemented.

The outcomes of this tax policy differential in combination – a broadly revenue neutral transfer of tax liabilities from council tax to higher income taxpayers – are consistent with the SG’s emphasis on fairness, progressivity and ability to pay as guiding principles of tax policy. But they are not revenue raising in combination.

Chart 3: Impacts on household income of tax policy differentials between Scotland and rUK

Source: FAI analysis of Family Resources Survey

Conclusions

The key thread linking the Scottish Government’s main tax policy decisions this parliament is the aspiration to impose lower tax rates for most taxpayers relative to those prevailing in rUK, but to adopt a more progressive overall tax structure – with highest income or highest value properties sometimes being subject to higher tax rates in Scotland than would be the case in rUK.

A cynic would argue with some justification that in some cases, the reduction in liabilities for some Scottish taxpayers relative to equivalent taxpayers in rUK is too marginal to make any meaningful difference to the taxpayers affected. In these cases, aspects of policy have arguably been designed with a slogan in mind.

But there can be no doubt that in some areas, the differences in tax policy that have opened up between Scotland and rUK have been substantial. Scottish tax policy has diverged substantively from prevailing rUK policy for higher rate income taxpayers and higher value residential property transactions. Council tax rates are substantially lower in Scotland than rUK.

Most of the SNP’s 2016 Manifesto Commitments on tax have been fulfilled – and where commitments have not been met, a reasonable justification has generally been made.

What might the next set of manifestos contain? Here are three sets of issues to watch:

- First, on the highly salient issue of income tax, to what extent do parties commit to unwind or maintain the existing policy divergence – and with what revenue effect?

- Second, a number of existing devolved taxes look ripe for reform to a greater or lesser extent. The reform of ratios between council tax bands was a very partial response to the more fundamental recommendations of the 2015 Commission on Local Tax Reform. This parliament has seen substantial reforms to business rates following the Barclay Review, but scope for reform may be necessitated by the impacts of Covid on the tax base and shifting business models.

- Third, will there be calls for transfer of further tax responsibility to Scotland, or to make more innovative use of existing powers? The Scottish Government has begun making a case for devolution of National Insurance Contributions, Capital Gains Tax and VAT. Meanwhile, the SNP’s 2016 Manifesto Commitment to increase the financial accountability of councils – through a part assignment of income tax revenues – has not really been progressed.

Perhaps it is unrealistic to expect that the detail of tax policy will play any meaningful role in the upcoming election campaign. But the next session of parliament is likely to be at least as busy on tax policy as this parliament has been.

You can read the full paper here.

Authors

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute