Last month, updated figures for labour market productivity in Scotland were published. They showed a relatively sharp jump in productivity– a rise of 3.5% in 2015.

This led the Scottish Government to conclude that the “figures show that Scotland’s productivity performance has grown around four times faster than the UK, providing further evidence of Scotland’s economic strength.”

This blog examines the recent trend in productivity in Scotland, and we unpick the numbers to see if they are as positive as would initially appear.

2015’s healthy boost to productivity

A couple of years ago – and in a welcome development – Scottish Government statisticians published a series measuring real-terms labour productivity in Scotland. The new data allows us to track productivity over time and how Scotland is fairing relative to the UK as a whole.

Real-terms productivity growth is fundamental to the long-term health of an economy. Broadly speaking, it measures the amount of output that is produced, on average, for a given amount of labour (usually measured in terms of hours worked). If we can produce more output (or better quality output) whilst still working the same hours then we will be better off. It is therefore an important indicator of economic performance and a key driver of long-term living standards.

Moreover, in an economy such as Scotland’s with little opportunity to grow our population (outside of migration) or to boost participation in the labour force beyond near record levels, productivity growth is the key to sustainable economic growth.

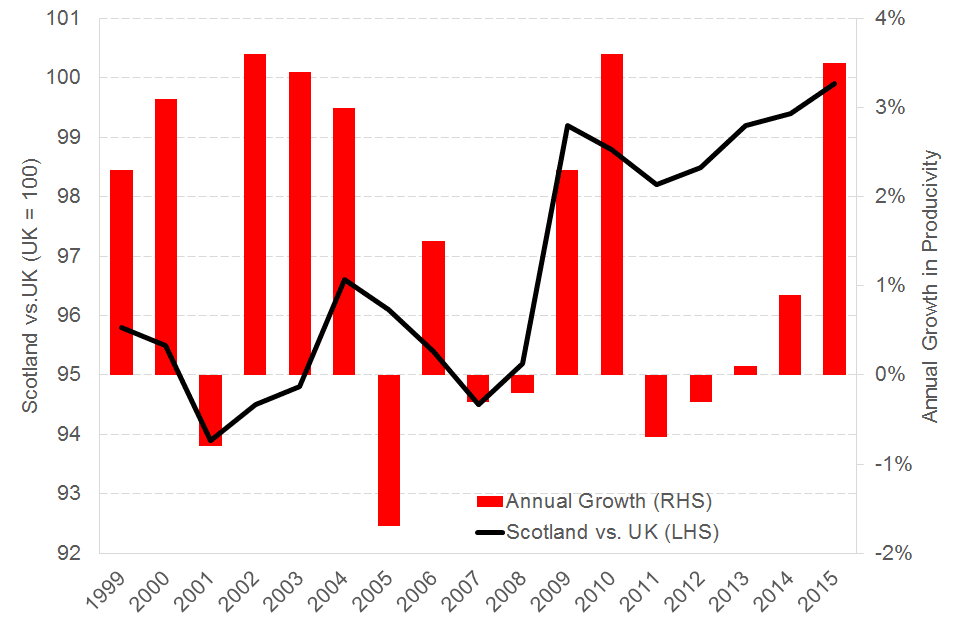

The chart below shows Scotland’s productivity performance since 1999.

The bars are annual growth (measured on the right-hand axis) and the line is our performance relative to the UK as a whole (measured on the left-hand axis in current prices and where we follow the convention and make the UK = 100 for ease of comparison).

Scotland’s Productivity Performance since 1999

Source: Scottish Government

Interpreting the results

A few things are worth noting.

Firstly, the surge in productivity in 2015 – as measured by output per hour – follows 4 years of weak (and sometimes falling) productivity in Scotland. To an extent therefore, this year’s figures appear to be a bounce back toward trend rather than evidence of a sustained improvement in productivity.

Secondly, the gap between Scotland and the UK has closed over the last 15 years or so. In 1999, Scotland’s labour productivity (in current prices) was around 95.8% of the UK equivalent figure whereas now it is 99.9%. In this regard, Scotland has caught up with the UK.

Thirdly, productivity in Scotland is now around 9.4% higher than it was just prior to the great recession in 2007. Interestingly, in terms of the key drivers of growth – population, participation, hours worked etc. – productivity growth has, in relative terms, been the strongest element in Scotland over this period.

So is this all good news?

At first glance, and looking just at 2015, the figures would appear to be relatively positive – both in terms of performance over the year and compared to the UK.

But there are reasons to be cautious, particularly if making conclusions about the underlying strength of the Scottish economy.

Firstly, and as pointed out above, the figures for 2015 come on the back of very weak growth across the previous four years. Key will be whether or not this trend continues. As we point out below, we don’t believe that this will be the case in 2016.

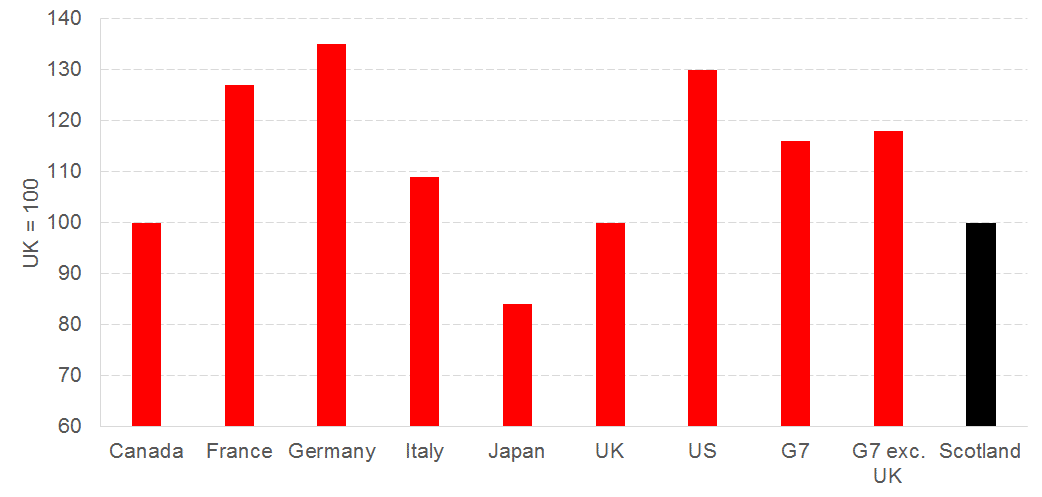

Secondly, while it is the case that we have caught up with the UK as a whole, the UK’s own productivity performance is dire when compared to our competitors. As the chart below highlights, UK productivity is around 20% lower than the G7 average (and well below the US, France and Germany).

International Productivity Performance (UK = 100): 2015

Thirdly, as with any economic statistic, it is important to understand what is actually driving any changes in measurement. The calculation underpinning productivity growth is relatively straight forward – it is the change in output per hour worked.

Now on balance, what we would like to see is the growth in productivity being driven by ever more output for the same level of hours worked. That means, people are still working the same hours and gaining the benefits of being in-work, but that overall we are able to produce more as a nation.

But productivity can also rise for another reason. It can increase – even if GDP is weak – if the number of hours people are working is falling as a result of more part-time working, or higher unemployment/underemployment. Clearly the economic conditions that underpin this scenario look very different and can be less positive. Workers for example, could be having to put in extra effort (with less time to do so) simply to maintain output at past levels.

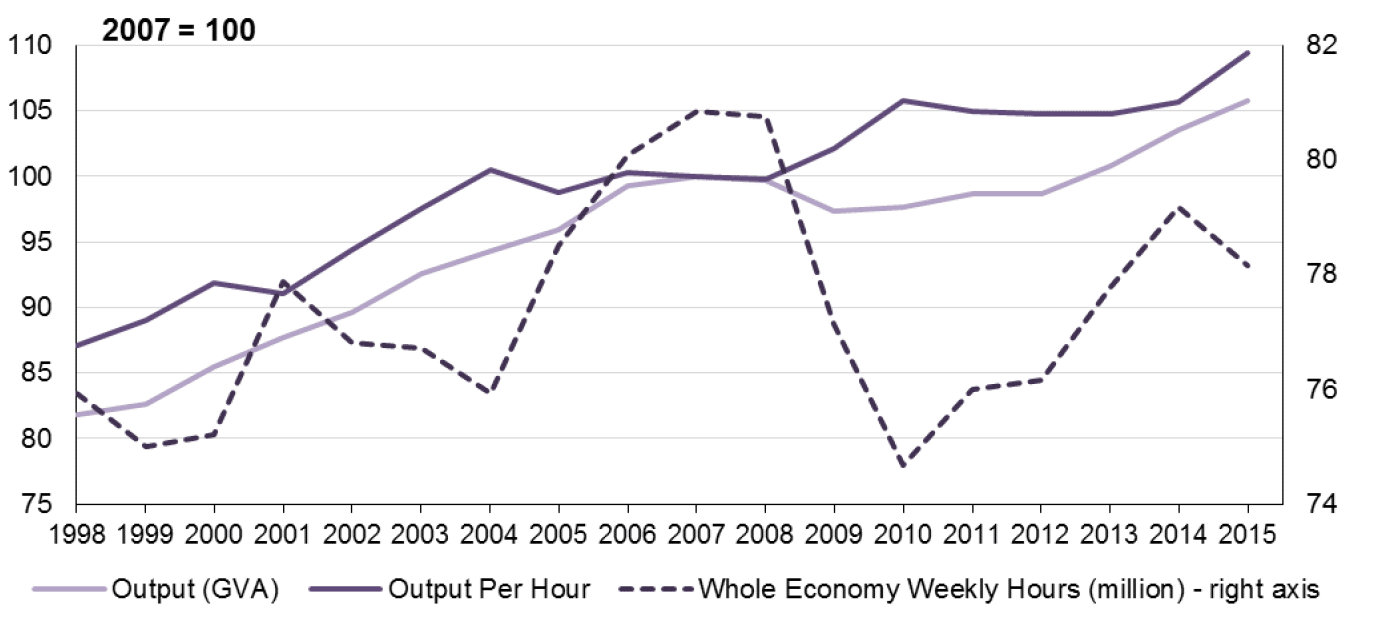

We see a bit of this in the most recent data, as highlighted by the chart below. In 2015, there was a slight fall in hours worked – and it still remains below its pre-recession peak. This fall helps to boost estimates of productivity growth on this occasion – as this picture from the Scottish Government statistical publication shows.

Real GVA and Output Per Hour, 1998 – 2015

Source: Scottish Government

The final – and most important reason – to be cautious about the recent statistics is the way in which they are calculated. As highlighted above, productivity is determined as the ratio of the growth in GDP divided by the change in hours worked.

But there are two methods to calculating GDP growth over a year.

One way, and the headline measured used in the Scottish Government’s GDP statistics is to compare the value of output today with the value of output 12 months ago. For 2015, comparing 2015 Q4 with 2014 Q4 gives a growth rate over the year of 1.2%.

The alternative measure is to take a so-called 4Q-on-4Q approach. This is effectively a rolling annual measure – which compares the most recent four quarters to the previous four quarters. It is this methodology that is used in the productivity calculation – and gives a much healthier growth rate of 2.1% in 2015.

Using an annual growth of 2.1% as opposed to 1.2% will clearly give a much larger estimate of growth in productivity.

Moreover, one well-known feature with using the 4Q-on-4Q methodology is that when an economy is slowing down, because it uses a much longer time period for comparison, the impact of any slowdown is delayed. Of course on the other hand, it underestimates the upswing.

Why does this matter now?

The 4Q-on-4Q methodology gives a healthy growth rate in Scotland of 2.1% in 2015. But if we use the same methodology for 2016 – and assume that growth comes in at the forecast 0.4% in the final quarter of the year – the 4Q-on-4Q estimate for 2016 growth in Scotland will be just 0.6%.

This suggests that unless hours worked fall significantly, it is highly likely that Scottish productivity figures published 12 months from now will show a fall or – at best – exceptionally weak growth.

So if policymakers are hoping that the recent statistics herald a new found surge in productivity in the Scottish economy then they are set to be disappointed.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.