In its latest forecasts, published last week, the SFC revised down its forecast for Scottish income tax revenues by £209m compared to its previous forecast in December.

In questioning the SFC on Wednesday this week, MSPs on the Finance and Constitution Committee seemed unanimously incredulous about this. That a forecast could be revised, in a relatively short period of time, by what is (in political terms) a significant sum, seemed difficult to fathom – particularly when the broader forecasts of economic output and employment had remained unchanged.

So why was the forecast revised down by £209m? Is the justification for the revisions reasonable? How significant are the revisions? And to what extent are we likely to see revisions of similar scale at future budget events?

First, why was the income tax forecast revised down in 2018/19 and beyond? In short, the downward revisions are due to the fact that the SFC has revised down its expectations of wage growth in each year of the forecast period.

On what grounds has it done this? It is partly because of the emergence of some new data on wage growth in 2017 since the SFC’s last forecasts. However, only limited new data on earnings has emerged since December, and on the whole this new data is not the sort that you would expect the SFC to place a significant amount of weight on (Labour Force Survey data on wages is drawn from a fairly small sample of self-reported earnings, while Compensation of Employees measures are derived from regional accounts data).

But the downward revisions to wages are also due to an ‘evolution of judgement’ on the part of the SFC about the likely future path of earnings growth. This evolution of judgement by a detailed analysis, summarised in the SFC’s report, of recent trends in Scottish wage growth , and the relationship between productivity and wage growth on the one hand, and labour market slack (i.e. unemployment, inactivity), and wage growth on the other.

The conclusion of this analysis is that real wages have grown ‘significantly weaker than we would have expected just from looking at changes in productivity and labour market tightness since 2010.’ (Para 2.48). The SFC discuss a range of potential explanations for weak wage growth, which include: limited confidence and increasing uncertainty (which may mean both businesses less likely to offer higher wages and employees less likely to demand them); rising non-wage labour costs; technological change; and structural change (including growth of low-paid, gig economy work, restructuring of the oil and gas supply chain, and declining construction sector activity).

Are these explanations reasonable? In themselves, yes. In fact these arguments reflect a growing literature describing explanations for weak wage growth in relation to both productivity and labour market slack, not only since the recession but preceding it. But what frustrated members of the Finance and Constitution Committee on Wednesday was that the SFC did not seem able to articulate why it had only occurred to them to consider historic trends in wage growth in their latest report, rather than in December. Forecasting is about judgement, and evolutions of judgement are to be expected. But when there is a sense that an evolution of judgement has been brought about by some analysis that could have been done last time, sympathy may be thin on the ground.

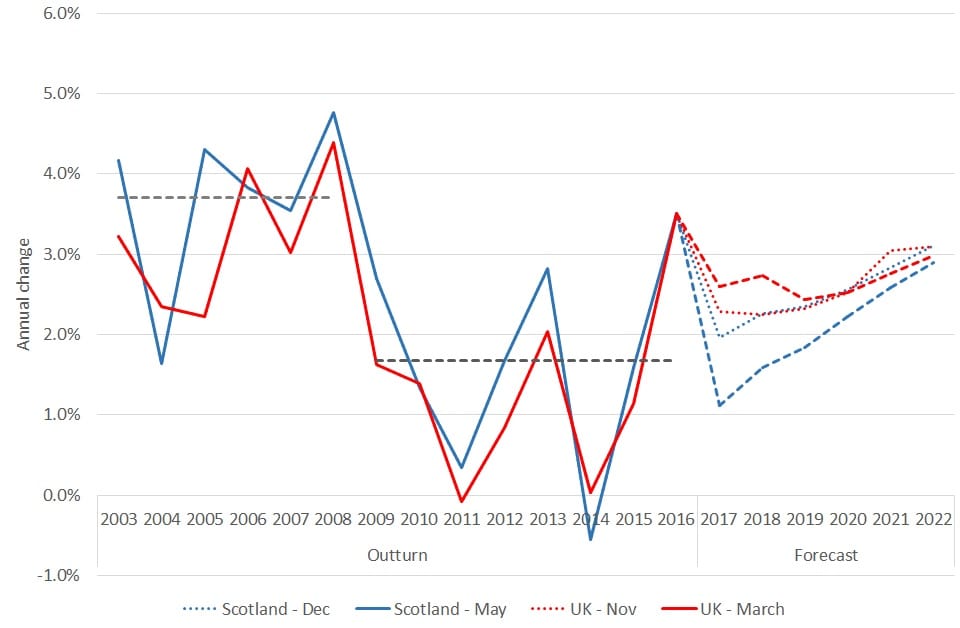

But it is perhaps too easy to criticise with hindsight. The chart below illustrates the challenges forecasters face. The chart shows the annual growth in gross weekly wages for Scotland and the UK between 2003 – 2016. (There are several potential sources of historic wage growth; this chart is based on the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, which is recognised as being one of the most reliable). Between 2003-8, wage growth averaged 3.7% in Scotland but ranged from 1.6% to 4.8%. Between 2009-16, wage growth averaged 1.7%, with a range from -0.6% to 2.8%.

The chart also shows the SFC’s projections for wage growth in December and May, as well the OBR’s equivalent forecasts for November and March. Since the end of last year, the OBR has revised its wage forecasts up, whilst the SFC has revised its down. Neither forecast looks unreasonable in the context of the recent past, although the extent of divergence in wage growth forecast over the next couple of years looks fairly unprecedented. (A similar chart can be made showing outturn and forecast real wages, but this doesn’t change the general story here).

Chart 1: Wage growth, outturn and forecasts

This leads us to the next question: are the revisions significant? The SFC argues not. Its income tax forecast was revised by 1.7% between December and May, which it argues is small in the historical context of forecast revisions. Indeed, the OBR’s forecasts for UK income tax in 2018/19 were revised by 2% between November and March. In other words, the OBR revised its forecasts proportionately more than the SFC did.

But the critical point here is that whereas the SFC’s revisions to Scottish revenues were down, the OBR’s revisions to UK revenues were up. The latter causes the Block Grant Adjustment, the bit deducted from the Scottish block grant to account for the loss of revenues by HM Treasury, to increase by £181m in 2018/19.

The combination of the downward revision to the Scottish income tax forecast of £209m and the upward revision to the BGA of £181m causes a deterioration in the Scottish Budget outlook of £389m compared to a few months ago. And £389m is clearly a very significant amount in the context of the Scottish budget (revenues from the Scottish Government’s tax policy changes in 2018/19 are forecast to raise jus under £220m).

The underappreciated point is that the Scottish budget is exposed to two sets of forecast errors – the SFC’s errors in respect of Scottish revenues, and the OBR’s forecast errors in respect of the block grant adjustment.

Should we expect to see revisions of similar scale at future budget events? The expectation was always that SFC and OBR forecast errors and revisions would generally go in the same direction. As long as they did so, forecast revisions/errors by the SFC in respect of Scottish revenues would largely be ‘cancelled out’ by a broadly similar error by the OBR in respect of rUK revenues (and hence the BGA).

But the challenge so far in 2018/19 (and 2017/18) has been that forecast revisions by the SFC and OBR have gone in opposite directions. And this year, the gap could have been worse – based on changes to the SFC’s wage forecasts alone, the Scottish tax forecast would actually have been revised down by over £300m in 2018/19, but some better news on revenue outturn in earlier years offsets that a bit, resulting in the final downward revision of £209m.

Given that the Scottish Government can only borrow £300m annually for forecast error, a reconsideration of these limits may be necessary in due course. And, with an expected balance of only £141m in the Scotland Reserve at the end of 2018/19, the Scottish Government may have some difficult decisions to make if the latest set of forecasts are realised.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.