On 11 June, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves will announce the outcome of the Spending Review. This will be a document in which departmental expenditure limits – or DELs, the allocations for each department to run discretionary programmes every year – are set for the coming three years.

The Spending Review will be a critical point of the current UK Government’s term. Having set the path of government spending for the next few years at the Budget, this is all about allocating it among competing demands. This is where priorities come into harsh contact with the reality of cold, hard cash allocations.

A long-established place at the centre of expenditure control

The Treasury’s control over expenditure is a long-established feature of the UK system, but even today it’s not a well codified one. Samuel Beer’s summary in 1955 analogised it to much of the UK’s constitutional framework: unwritten, formed of guidelines rather formally enforceable laws, and relying on goodwill.

The Treasury’s position was strengthened considerably during William Ewart Gladstone’s tenure as Chancellor. A number of principles were established, many of which (for good or ill) have since endured for the most part.

The first was a focus on annual cash control through the presentation of Estimates in advance of the year beginning, which would be challenged in the House of Commons through the Committee on Supply (later the Estimates Committee). These were not small select committees of the sort we’re now used to seeing, but rather the equivalent of a Committee of the Whole House. Proposals could be made by any member to amend the Government’s Estimates, and indeed they initially were – although, as highlighted by Gwyn Bevan in his 1980 historical survey, this ceased to be the case over time, with supply becoming a matter of confidence in the government.

The second principle was that of balancing Estimates of public expenditure in the Budget by adjusting taxation accordingly. This was based on the doctrine of balanced budgets (or ‘sound money’, as Gladstone would have put it), which prevailed in the Treasury until the Second World War. In some sense, however, the Estimates’ relative place would be maintained for much longer: they were presented before the start of the year, usually in advance of the Budget, at which point the Chancellor would have to determine how to finance the already presented public spending commitments.

And finally, the Treasury’s focus was on being parsimonious with the public purse to minute detail – to the point of “saving candle-ends”, in Gladstone’s words. This is perhaps the Treasury’s biggest reputation, that of a miserly penny-pinching department ready to strike down the prospect of spending on any expensive projects.

As Bevan puts it, there is a more benign view of this undoubtedly sceptical eye that the Treasury casts over new policy, and which is corroborated by Beer’s take. While spending departments in negotiations represent the interests of their area of competence, the Treasury’s role is to be a voice for those not in the room but who must nonetheless finance the requested spending. It’s an adversarial internal dynamic perhaps fitting for the adversarial Westminster system.

Public spending planning reimagined

In the post-war years, the Estimates process became increasingly unfit for the modern state. For one, the increase in social security spending was highly demand driven, and made it hard to predict expenditure needs accurately. Supplementary Estimates had always been used as a way of authorising additional spending during the year, but as noted by Bevan, levels of scrutiny had declined while usage had increased in the years since the Gladstonian reforms of the 1860s.

With that in mind, then-Chancellor Derek Heathcoat-Amory accepted the Estimates Committee’s recommendation that an independent report be conducted on how the Treasury’s control of public expenditure did and ought to work. Lord Plowden’s committee reported in 1961, with the principles underlying it being collective decision-making amongst Cabinet for public spending decisions.

Collective decision-making would be a stark departure from the centrality of the Treasury. There had always been a way for minister told ‘no’ by the Treasury to appeal to Cabinet, but even there it was the Prime Minister’s authority – as First Lord of the Treasury – that would underpin any overruling of the Chancellor’s decisions. What Lord Plowden proposed was altogether different – the sort of government that is much more prevalent these days in Mainland Europe, where the finance minister is one among many voices in a council of ministers.

In line with this, the Plowden Committee recommended a procedure that would become standard over the course of the next decades – the Public Expenditure Survey, or PES, which Selwyn Lloyd adopted. This was to be a regular survey of departments’ plans for expenditure, according to rules agreed by the Cabinet. The approach in practice fell short of being full collective decision-making, but it did succeed in relieving the Treasury of some its duties in terms of monitoring details of spending in other departments.

Once agreed, the PES results would be shared in secret with the Cabinet, which then agreed on plans on the basis of the survey. This came to be published annually as a White Paper to Parliament, detailing spending plans over the coming years.

One of the intended features of the PES was that it should reflect the likely medium-term resources of the country, and therefore encourage less short-termism than the annual Estimates process. But as Bevan highlights, the process was found wanting on several fronts. There was little in the way of an agreed baseline, for a start – the Plowden commission suggested growing expenditure in line with output, but that proved to have no political bite. Assumptions about medium-term conditions also proved to be much too optimistic during the 1960s and early 1970s, as a consequence of economic fragility and difficulties in financing spending as we detailed in our look at historical budgets.

The process itself also came to immensely complicated. The objective was to move away from controlling cash expenditures to controlling ‘volumes’ – that is, the actual levels of output produced, or numbers of staff employed, or goods and services purchased.

This may seem like a good idea in principle. Surely governments should plan how much they want to achieve and what they want to deliver? But implementing it was a nightmare. It involved using some measure of fixed prices to convert volumes into cash figures which could then be uprated to be voted by the House of Commons. Towards the end of the year, Supplementary Estimates would then be used to account for inflation and obtain approval for additional spending.

Losing control, or Horse Guards Road strikes back

But by far the biggest issue with the volume regime of the PES is that it didn’t work in controlling expenditure. Perhaps it could have done so – or at least not been as clear that it didn’t – in a time of lower inflation and with fewer constraints on public spending.

As it was, the stresses of the early 1970s inflation did for the PES in its original form. It’s all well and good to plan on what needs to get done (and even that was exceeded systematically in the early 1970s), but if prices rise significantly in the meantime, not everything that was planned is affordable anymore.

That’s because the ultimate constraint on government spending decisions is how much it can finance, not what its own survey of how much it would like to do says. In 1975, it became clear that runaway inflation was making it harder and harder to borrow the amount needed to make good on the inflation effect on government programmes. The Treasury’s control was limited to the PES volumes – the inflation effect was effectively automatic, as Darcy Luke’s thesis explains.

To combat this, Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced on the 1st of July of that year that cash limits on all discretionary programmes would be set out by the Chancellor for the financial year 1976-77, as part of the “Attack on Inflation” White Paper. These would be strict limits on spending in the first year of the PES planning period – essentially the only year that fully mattered, as every year the plans would get revised. This was a makeshift innovation, one that maintained the idea that the PES was still in place while effectively reverting back to one-year settlements.

Cash limits were very unpopular in a divided Cabinet of a government that by then had only a sliver of a working majority. As Bevan and Luke both highlight, however, they succeeded in re-establishing Treasury control over total expenditure and – as intended – in squeezing public spending.

In fact, cash limits were so successful in wrestling back control of the public purse that, as Vernon Bogdanor pointed out, they reduced the deficit to the point that it might have made Britain’s loan from the IMF in 1976 unnecessary were it known in advance. But without knowing it in advance, Chancellor Denis Healey acquiesced to further spending cuts than he’d have liked as a condition of the loan, and opening further the rift with Tony Benn and Barbara Castle’s wing of the Labour Party.

Healey’s fury with the underestimate of the effectiveness of the imposition of cash limits is purported to have been the motivation for one of his great aphorisms – that an economist is someone who, when asked for a telephone number, gives you an estimate – but it is likely misplaced. The UK may have only needed to draw down a portion of the loan and been able to repay it early, but to focus on this is to misunderstand the main channel through which the IMF intervention operated. Britain was in a position where it couldn’t finance its deficit on the open market, and actively risked running out of reserves while defending the currency if its holders of debt decided to dump it.

The IMF loan, then, bought the Government time and financing certainty to bring spending back into control. It took it out of the firing line of the financial markets’ ultimate constraining power, preventing perhaps more drastic and quicker cuts to public spending.

We’re still living with the 1970s spending control architecture

The 1970s were a transformational decade in terms of the infrastructure of Government in the UK. For example, it was the inflation crisis that precipitated the introduction of pay review boards for public sector occupations, and it was the fast-changing pace of the crisis that brought about the (now so damaging) system of two economic and fiscal forecasts a year.

And the same long-lasting legacy persists in terms of spending control. Some of the details from the original 1976-77 Cash Limits publication might be slightly different from what we’ll get in a few days’ time: there’s only one year of limits (although not all Spending Reviews have been multi-year in recent times) and on top of departmental limits, there are also limits by programme. But the fundamental architecture in which limits for spending are set out in a separate publication outwith the Estimates process and which supersedes it has essentially remained the same since then. If then Chancellor Healy and Permanent Secretary to the Treasury Sir Douglas Wass saw what Rachel Reeves will publish, they’d barely bat an eye-lid.

The cash limits framework also distinguished for the first time formally between demand-led and discretionary spending. The former has since morphed into annually managed expenditure, or AME, on which any shortfall must be made good, provided claims comply with the rules set by departments. Social security is an example of this, as are student loans, public sector pensions or debt interest payments.

Discretionary spending, on the other hand, is these days called departmental expenditure limits, or DEL. This includes the running costs of providing services such as the health service, schools, investment in transport infrastructure, and essentially any other area in which the government is directly involved in provision. These are the items that were then subject to cash limits, and are now part of the Spending Review process.

In many ways, the cash limit spending architecture is remarkably simple. The Treasury sets out how much each department can spend, transferring the risk of managing pay claims and the finding of savings to fund any other pressures to each department.

It also cements the Treasury’s centrality in the Whitehall financial architecture, giving it the power to play hardball with departments. As Bevan illustrated back in 1980 – not even a handful of years after their introduction – cash limits have since their introduction been a way of the Treasury squeezing growth in public spending by setting them below demands from the departments. It was also a useful tool for avoiding an explicit incomes policy for public sector pay, while essentially conditioning what departments could offer.

The success of cash limits in curbing growth in public spending was significant but not complete – partly due to the loosening of pay restrictions at the tail-end of the Callaghan Government. Both Colin Thain and Maurice Wright’s 1995 and Tony Prosser’s 2014 studies describe how the incoming Conservative administration from 1979 onwards pushed to reinstate restrictions on growth in spending through the PES process and the cash limits. This culminated in the PES moving to a cash basis in 1981, essentially removing the volume planning element it originally had and bringing it much closer to today’s multi-year fixed settlements.

To be seen to have a stooshie is no bad thing

Spending budgets were back then fully negotiated on a bilateral basis between the Treasury and the relevant department. The Treasury’s control of the process, as we saw before, ebbed and flowed over time. The infrastructure that the Treasury created and maintained to ensure that control also evolved, with subcommittees of Cabinet attempting to strengthen its role from 1965 to the mid-1970s and from 1978 again.

These arrangements were meant to solve dispute, but in a relatively collegiate way. This became less so in the early 1980s, when the feared ‘Star Chamber’ became part of the Cabinet process of agreement of programme allocations. This brought the process back into a confrontational setting, where ministers were effectively interrogated and could be strong-armed into agreeing to difficult cuts to deliver by the William (later Lord) Whitelaw-led committee.

Thain and Wright’s description of its operation and how difficult it is to tell if it worked as a way of asserting control of the process is in many ways familiar to those of us who worked in the Civil Service in later years. It certainly encourages a ‘war gaming’ mentality where both sides exaggerated their positions to end up conceding several points while appearing to have a significant stooshie about them. It’s therefore not dissimilar to the ‘shroud waving’ you may have heard about lately, and it remains an integral part of the process.

The final furlong on the road to today’s system

The 1990s proved to be a time of some steps towards the current system. The Star Chamber’s power ebbed and flowed with the Thatcher Government’s popularity, with pressures for a looser grip on spending eventually carrying the day. The Chancellor’s control was somewhat reasserted during John Major’s premiership, when the ad-hoc Star Chamber morphed into the Chancellor-led EDX Cabinet Committee.

Further control over the process came in 1993, when Ken Clarke unified the timing and process for tax and spending into the Budget Statement. Chancellors had often complained – especially when coming into office – that spending decisions had already been made and this hindered their ability to make a holistic judgement of the course for the public finances.

In reality, this changed things less than it might seem at first. Despite the Estimates process being separate and often set prior to the Budget, Chancellor after Chancellor had actually significantly changed spending plans to make the Budget add up, though often in quite opaque ways. Transparency did improve, but the fundamentals of fiscal policy were hardly shaken up.

The locus of control over expenditure also evolved during this time. Until 1992-93, the Government’s focus was squarely on a broad planning total, and its scope had increased considerably since the days of the volume PES. Even when cash limits were introduced, they only applied to around 40% of total government spending, as Healey’s Treasury recognised that significant strands of spending were demand-led – social security being the largest of them.

But Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson’s Treasury in the 1980s expanded this to cover nearly all of public spending with the exception of debt interest and locally financed spending. A tighter definition, but one which left the Government’s plans excessively at the mercy of the business cycle.

In the aftermath of the Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis of 1992, and – as Rowena Crawford, Paul Johnson and Ben Zaranko’s 2018 paper details – at a time of reflection on the part of the Treasury about the adequacy of its arrangements, the New Control Total was introduced. This was still a very broad set of limits, covering around 85% of all public spending, but crucially excluding the most volatile elements of social security – a much more sensible way of controlling expenditure from the centre.

The 1998 Comprehensive Spending Review

The formal system of budget setting and control in place today is a product of the New Labour Government and of Gordon Brown’s Treasury, but its roots – as we saw – lie further back in time. But it was also not an immediate change implemented at soon as Brown entered No. 11 – the July 1997 Budget stuck to the previous government’s control totals for 1997-98 and 1998-99, and set out the timeline for the 1998 Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR).

The name echoed the Fundamental Expenditure Reviews conducted by departments in 1993 and 1994, but the outcome of those was essentially to hold down pay in the public sector. Instead, the CSR would replace the PES as the planning system for public expenditure. It promised to be a ‘zero-based’ review, which meant (in theory) that the Government would start with a blank sheet of paper and departments would have to justify each programme of expenditure, regardless of whether it already existed or not.

Whether the 1998 CSR really was fully zero-based – and whether that really is as desirable as it might seem at first – is a matter of debate. It’s hard to see it being more comprehensive than the full PES used to be – but simplicity is not necessarily a bad thing. The PES was clearly overengineered and at times confused even the Treasury (see Bevan’s paper), a product of a time when 5-year central plans seemed like they might work.

The 1998 CSR implemented the split between DEL and AME spending that we discussed earlier, and brought into direct Spending Review control about half of all public spending. It also moved towards multi-year planning in a more formal way, setting cash limits on resource and capital at a departmental level for three years.

A way of divvying up an already-set envelope

Although the CSR is the most well remembered publication relating to public spending in 1998 and marked a significant event for Whitehall departments, as well as for defining the priorities the public would judge the Government on, its macroeconomic role was relatively minor. This is true of nearly all spending reviews since then too.

That’s because spending reviews are merely a way of allocating spending within totals that have already been set. Even in 1998, the overall envelope had already been set the month before in the Economic and Fiscal Strategy Report. Since then, spending reviews have (broadly) stuck to envelopes announced at the previous fiscal event. So even if some types of spending do have different effects on the economy, the differences between them are relatively minor – and the level of spending is determined alongside a broader set of considerations at a Budget or similar fiscal event.

Spending reviews have been relatively minor since the first one – apart from 2010

The New Labour Government ran four other spending reviews, in 2000, 2002, 2004 and 2007. The 2000 and 2002 Spending Reviews in particular presided over fast growth in spending – faster even that the 1998 CSR. Health and education in particular saw big increases.

By 2007, the pace of increase in spending was slowing considerably. But by far the biggest change in policy came in 2010. That spending review itemised the large cuts to spending that had been announced by the previous Chancellor Alistair Darling and turbocharged by new Chancellor George Osborne.

Only four departments were spared real-terms cuts over the five-year period: Health, International Development, Work and Pensions and the Cabinet Office. It included planned real-terms cuts by 2014-15 of 51% to Communities spending, 27% to Local Government and 23% to the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice. Even with the increase in health spending – the single largest department by a factor of four – planned resource spending cuts amounted to a cumulative 8.3% by 2014-15.

The next two spending reviews were much smaller in comparison, but broadly aimed to contain spending growth in real terms. The next inflection point was 2019, when the Spending Round – Sajid Javid’s only major statement to Parliament during his tenure in Number 11 – included significant increases in spending. But that came after several years of previous Chancellor Philip Hammond progressively loosening spending at each fiscal event. In any case, any plans were majorly disrupted by Covid, as were those from the 2020 Spending Review.

2021 was a return to a more standard multi-year budgeting framework – 2019 and 2020 were both one-year rollovers, the first disrupted by Brexit and the latter by Covid – and also one which tried to rein back the growth in spending seen in previous years.

Does this system of expenditure control work?

It depends what we mean by ‘work.’ In a formal sense, the UK system is remarkably good at avoiding breaches of the control total. This is the main aim of the system: the Treasury wants to avoid departments incurring expenditure outwith its control and outwith the approved limits set. So from this point of view, the Spending Review and DEL framework would seem to be a remarkable success. Departments almost always underspend their limits, and (apart from the retrospective Excess Votes due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2019-20) breaches are rare and minor. This has been the case since the imposition of cash limits in the 1970s.

On the other hand, one might ask to what extent these limits really are as hard as they seem at first, and therefore to what extent they actually constrain public spending. Even if we exclude the 2019 and 2020 Spending Reviews, for which spending took place during the pandemic and obviously required time-sensitive increases in spending, there is evidence that the Government has topped up budgets significantly during spending review periods.

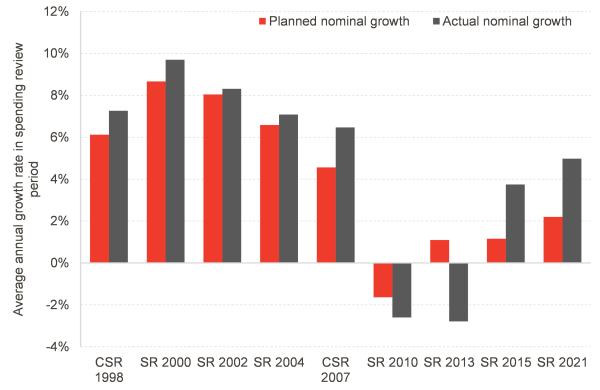

Chart 1 shows the annual increases in limits set to departments in nominal (i.e. in cash) terms. This is what spending reviews should be good at: passing on the risk to departments by setting cash budgets, which mean that each area needs to then manage competing demands within a set limit.

Instead, what we see is that apart from the austerity years – in which cuts actually exceeded plans – spending growth has been consistently higher than that projected in each spending review. The gap has grown over time, with spending in the SR 2015 period more than three times that planned by George Osborne, largely as a result of Philip Hammond’s looser policy. Growth in the SR 2021 period has also been twice as fast as Rishi Sunak intended as Chancellor, even with him eventually stepping into Number 10.

Chart 1: Nominal annual increases in departmental expenditure limits in each SR period

Source: HM Treasury, OBR, FAI analysis

This consistent pattern of top-ups and policy between spending reviews is not really surprising. In some sense, it merely reflects the fact that the spending review process – for all the work it generates in Whitehall – is not actually a major macroeconomic event. That place is taken by Budgets and Summer/Autumn/Fiscal Statements (Winter has so far been avoided in the title, presumably to avoid headlines writing themselves in the case of bad news), in which the Chancellor does actually have to balance tax, spending and borrowing in line with political, economic and market conditions. All that is absent from a spending review.

What about real-terms spending?

When the PES was introduced, it was meant to be a solution to the excessive control exercised by the Treasury, which created a barrier to expansion based on population demands for additional government provision of goods and services. In particular, the planning system was changed to be on the basis of volumes rather than prices; the Government would decide what it needed to do in terms of quantities, and would then provide funding for any inflation effects.

This is largely what caused the loss of control over spending in the 1970s, resulting in the imposition of cash limits. Of course, what this actually meant was that if inflation was below forecast, departments would be able to increase spending within that envelope and provide more goods and services. But if it were higher than forecast, then departments would have to live within their limits and cut provision. Essentially, the inflation risk was outsourced to departments.

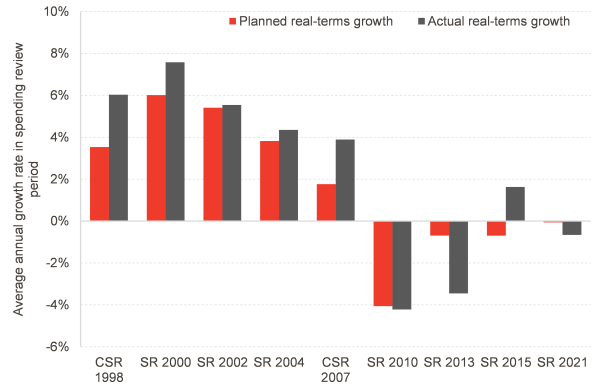

Chart 2: Real-terms planned and actual spending by departments during each SR period

Source: HM Treasury, OBR, FAI analysis

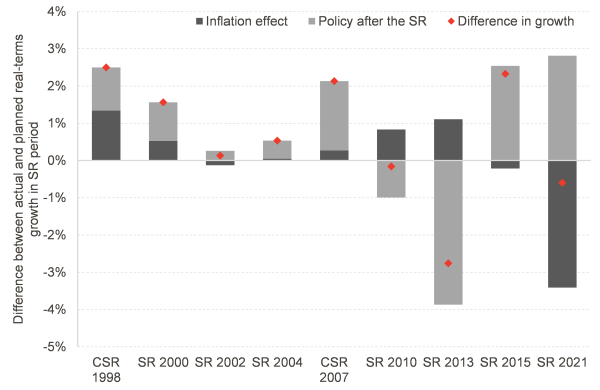

In fact, that is largely the pattern that we see since the 1998 CSR. Chart 3 shows this in more detail, breaking down the difference between planned and actual real-terms spending into an inflation effect and the provision of additional funding by the government in periods after the spending review. Note that the inflation effect is positive when inflation is lower than forecast – that is, lower inflation frees up funding for higher increases in real-terms government spending.

Chart 3: Breakdown of difference between planned and actual real-terms increases in spending during SR periods

Source: HM Treasury, OBR, FAI calculations

In the period after the 1998 and 2000 spending reviews, inflation was significantly lower than forecast, which allowed the UK Government to increase spending considerably above what it had planned originally. But even then it also engaged in significant top-ups during the SR period, meaning that the pattern of not sticking to the announced limits has been a feature of the system since its introduction.

The austerity years also show that the Osborne Treasury used lower than predicted inflation to slash spending more aggressively, essentially offsetting any loosening that could have come from that inflation surprise. It also cut aggressively the totals for 2015-16 after the SR 2013.

The Hammond loosening is very evident in this chart as well, bringing annual growth in spending to 2.3 percentage points above Osborne’s plans from 2015. And finally, the return of the inflation erosion of the purchasing of departmental budgets is clear from the SR 2021 bars. Jeremy Hunt increased totals in his budgets, but not by enough to mitigate the inflation effect: spending fell by 0.7% a year in real terms, compared to the already significantly tight 0.1% fall pencilled in by Rishi Sunak.

What can we expect next week?

As we’ve outlined above, the envelope for the 2025 Spending Review has been set since March. There may be some small movements either way, but ultimately it will be very close to what the Chancellor included in her plans at the Spring Statement and the OBR scored in its Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

We’ll focus on RDEL, which is day-to-day spending and therefore the most crucial allocation for public service delivery in the short-run. Table 1 shows just how uneven the profile is for growth in spending: slower in 2026-27 already, and down to only 1% a year from 2027-28 onwards.

Table 1: RDEL allocations from the Spring Statement 2025 and Main Estimates 2025-26

| 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | |

| RDEL (£bn) | 487.5 | 514.8 | 535.5 | 551.6 | 567.7 |

| Assumed RDEL excluding international aid (£bn) | 476.5 | 502.6 | 529.0 | 544.9 | 560.8 |

| Real-terms growth | 2.9% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 1.0% | |

| Real-terms growth excluding international aid | 2.8% | 3.5% | 0.9% | 1.0% |

Source: HM Treasury, OBR, FAI analysis

The totals in the Spring Statement already had the shift from international aid to defence spending, which when we put it all together actually leaves slightly more room for manoeuvre in the first year of the Spending Review on the resource side for all other departments than might seem at first.

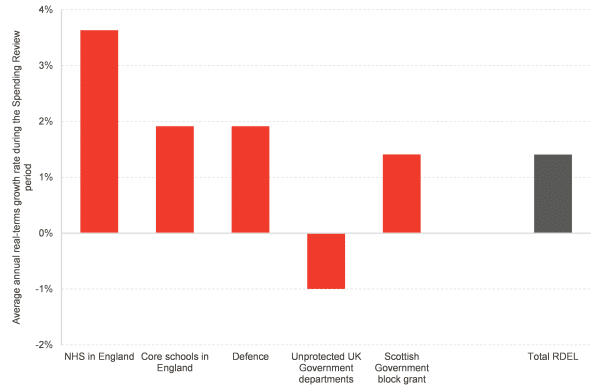

But that is very much short-lived. And with the health service, schools and defence likely to be boosted in real terms, it leaves a very difficult settlement for the final years of the Spending Review.

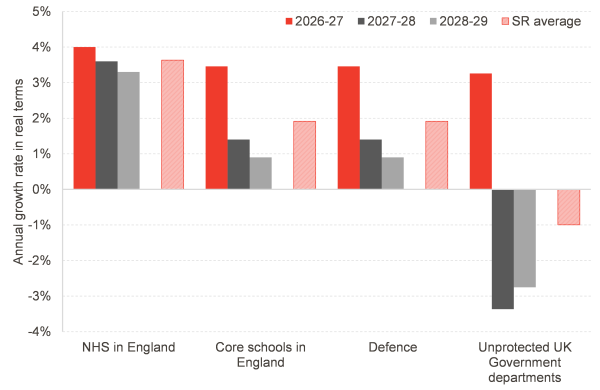

Chart 4 illustrates a plausible scenario in which the English NHS sees an increase of 3.6% a year in real terms, with schools and defence also seeing around a 2% boost a year. None of these are historically large, but even this mild scenario would leave unprotected departments having to cut spending significantly, by 1% a year in real terms. This would fall disproportionately on 2027-28 and 2028-29, as there is a significant boost in the first year. It might mean 2.5% to 3.5% cuts a year in real terms in two consecutive years.

In this scenario, the Scottish Government’s block grant would mechanically move similarly to the overall envelope. This is because many of the changes to unprotected departments lead to Barnett consequentials, but so do the larger boosts to health and education, which offsets those changes.

Chart 4: Illustrative RDEL scenario for the Spending Review based on announced policy and total envelope

Source: FAI analysis

It is of course for the Chancellor and the UK Government to decide on the path of public spending – and it might well choose different paths for spending. But chart 5 is not an implausible extrapolation of the figures that are already in the OBR forecasts and which guide the Spending Review totals.

And it does not look like a particularly deliverable plan. It promises a sort of ‘mañana austerity’, with strong growth in spending for another year while continuing to promise to cut spending at pretty heroic rates in a few years’ time. In fact, it’s almost a perfect reverse image of what then-OBR Chairman Robert Chote termed George Osborne’s spending ‘rollercoaster.’ Maybe we’re just on a different section of the ride.

Chart 5: Implied annual real-term growth rates from the illustrative RDEL scenario for the Spending Review

Source: FAI analysis

But as chart 3 showed, spending reviews are far from the only time at which fiscal policy is announced. A cynic might suspect that the Chancellor knows this and is planning on finding a way of not having to deliver those planned cuts in 2027-28 and 2028-29 – perhaps by hoping for economic growth to bail her out, or raising taxes significantly at a coming budget. Either way, she’ll want to avoid trade-offs on public services that are hard to stomach.

But that seems to be for another day, may even another year. Augustinian fiscal policy is alive and well.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.