In June, as part of our work with Serving the Future, a three-year research project into the hospitality industry, we published the results of a study that involved hospitality owners and managers discussing the biggest drivers of change in their industry. In this study, we created a workshop and gave these industry leaders a forum to discuss the biggest potential drivers of change for their businesses and the industry as a whole. A major theme of the discussion was about the efficacy of government policy, particularly concerning the educational system. They felt that prospective workers are not set up with the necessary skills required to work in hospitality, and that the system as a whole is confusing and difficult to navigate.

This workshop took place in September and gave us an insight into the skills development landscape in Scotland from one perspective. In May, an economy-wide report on the post-school learning system came out with similar results: that the current skills delivery landscape is confusing, disjointed, and creates “significant tensions” between educational institutions, industries, and the government. It is important to note that all sides have good intentions and good ideas, but the overall structure of the system lacks cohesion and clarity.

These two perspectives led us to a question – how do hospitality workers interact with the educational system, and how does the education system support the hospitality industry?

Skill gaps in hospitality

The hospitality sector is important in Scotland – employing around 164,000 people and adding nearly £6 billion to the Scottish economy in 2022. However, hotels and restaurants face higher vacancy rates and lower wages than any other industry. These issues are compounded by higher skills gaps in the hospitality sector relative to other industries.

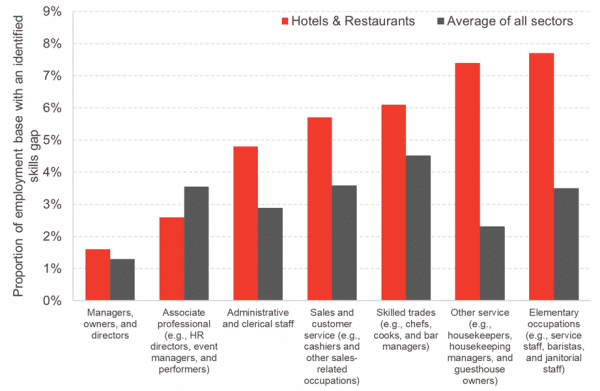

Chart 1 shows a breakdown of skills gaps across various occupations in hospitality relative to the rest of the economy.

Across all sectors, the skills gap in “elementary occupations” was 3.5% according to the Scottish Employer Skills Survey, a 2020 survey which interviewed around 3,500 employers. This means that, across all industries, businesses found that around 3.5% of workers in elementary occupations were missing one or more necessary skills.

In comparison, elementary occupations in the hospitality industry – which includes jobs like servers, bartenders, baristas and cleaners – had a skills gap of nearly 8%. Around half of all hospitality workers fall under the elementary occupations category, with an additional 30% falling under skilled trades (chefs, cooks and bar managers) and manager categories.

Chart 1: Proportion of staff across all employers that are not fully proficient, by occupation, 2020, Scotland

Source: Scottish Employer Skills Survey, 2020

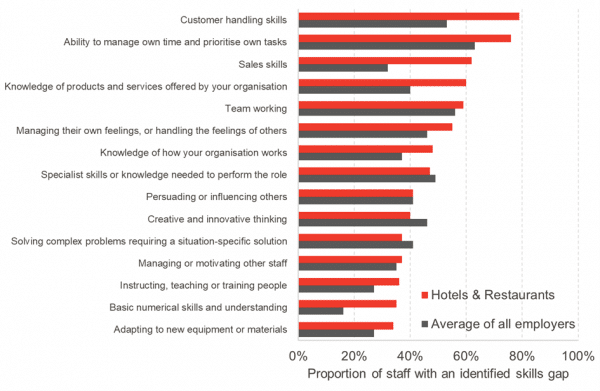

Of all staff with an identified skills gap, customer skills, time management, and interpersonal skills were notably more extreme in hospitality than in other industries. Organisational knowledge gaps were also larger than in other industries (Chart 2).

Survey data likely misses something important here – how bad are these gaps? For example, a high proportion of staff members may struggle to manage their time, but their employers may not feel particularly bothered about this skill. Meanwhile, a lower proportion of staff members may struggle with specialised skills but lacking this skill may be significantly harder for managers to deal with.

Chart 2: Most common skills gaps among hospitality workers, 2019-20

Source: Scottish Employer Skills Survey, 2020

Hospitality and education

Hospitality employers pointed out significant proficiency gaps among sales and customer service staff, elementary staff, and skilled trades. These gaps can be – and often are – bridged by on-the-job training, but given tight budgets, low profits, and an overall lack of time, it’s difficult for employers to provide this sufficiently. Education is another way to bridge these gaps. This leads to two possibilities regarding the way hospitality interacts with the education system:

- Hospitality workers do not participate in formal education

- Education is unrelated to career paths for hospitality workers, either due to choices or to a gap in the educational landscape

Are hospitality workers engaging in the education system?

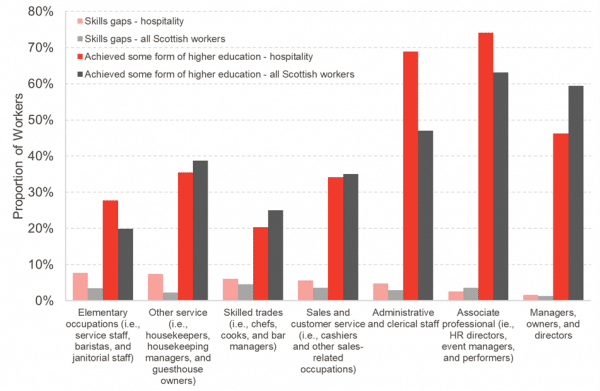

The occupations with the highest skills gaps (elementary occupations, other service occupations, and skilled trades) have the lowest levels of formal educational attainment. Skilled workers in hospitality, in particular, are less likely to have post-secondary qualifications and more likely to have skills gaps compared to other workers in skilled trades (Chart 3).

Jobs in elementary and other service occupations tend to be low paid, so we would generally expect these workers to have low levels of education. Surprisingly, however, elementary workers in hospitality are much more educated than those in other industries, even though they have a higher skills gap.

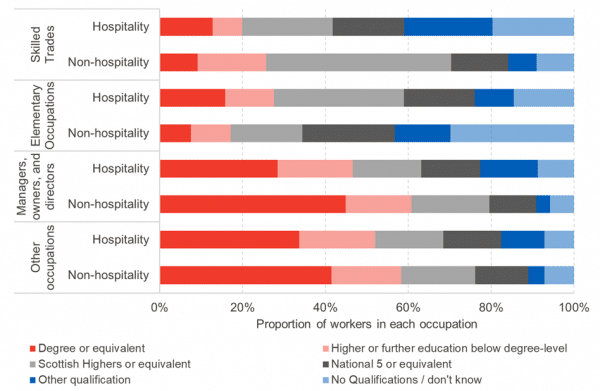

Skilled trades workers in hospitality are also more likely to have a degree than non-hospitality workers, although they have lower levels of qualification overall (Chart 4).

Chart 3: Skills gaps and higher educational achievement for Scottish hospitality workers compared to Scottish workers across all industries, organised from largest hospitality skills gap to lowest, 2019-20

Source: Annual Population Survey 2019-20, Scottish Employer Skills Survey, 2020

Chart 4: Educational attainment for Scottish hospitality and non-hospitality workers who were not in any form of formal education by occupation, 2019-20

Source: Annual Population Survey 2019-20

Although hospitality workers in elementary occupations have higher education levels, there isn’t data on what their education consisted of. There’s also a stereotype that these hospitality workers may be taking a temporary job while in university, or that they might be a recent graduate while looking for more suitable and permanent work.

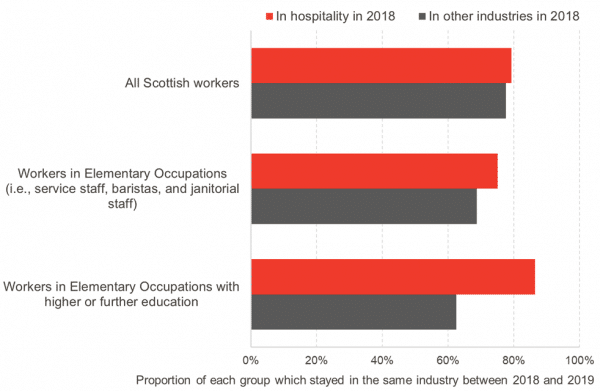

Even if this is true, once workers are in hospitality, they don’t seem to be moving into other industries quickly. For instance, in the two-year period before the pandemic, hospitality workers were slightly more likely than non-hospitality workers to stay in the same industry. Servers and bartenders with some level of higher or further education below degree-level, notably, were much more likely to stay in hospitality jobs over these two years compared to other workers (Chart 5).[1]

Chart 5: Proportion of workers that were not in education that stayed in the same industry over a two-year period (2018-19)

Source: Longitudinal Annual Population Survey, 2018-19

These jobs are clearly not temporary, even for those with higher levels of education. This may be due to personal choice, but there is also evidence that it can be difficult to get out of low-paid work once in it. Some people may also go into hospitality work because it allows them to balance other priorities, such as family caring roles or health issues, that might prevent them from finding work in other industries.

For those that do choose to work in the industry long-term, this leads to the next possible relationship between hospitality workers and the education system – that hospitality workers are, for some reason, not gaining the necessary skills through education.

Does the education system fail to meet hospitality workers’ skills needs?

While we don’t have data on whether degree-educated servers and bartenders are more likely to have customer service gaps than their colleagues with fewer qualifications, it’s likely that people are choosing education paths unrelated to their career. In that case, there isn’t much that the education system can do to prevent this skills mismatch. If someone earns a degree in maths, for instance, but decides that she likes and wants a career working in restaurants, there’s no reason for schools to adjust their mathematics curriculum accordingly.

Discussions with hospitality leaders revealed that the education system is difficult to work within, and that employees with relevant education have frustrating skill gaps anyway. There are several areas where they felt that the Scottish education system could be more supportive, such as:

- Focusing hospitality education on practical and industry-specific soft skills, such as preparing people to work nights or weekends

- Additional government support for training and retaining staff

- Preparing people to work in evenings and on weekends

- Overall accessibility, especially in rural areas

It’s interesting that soft skills were highlighted as an area that education systems fail to cover. In fact, customer service skills are a notable part of hospitality curricula. This shouldn’t invalidate the concerns of employers, however: SCQF qualification statistics show that very few people enrol in the courses that would match these skills. In 2022, less than 600 qualifications below degree-level were attained in general hospitality, management, or events, compared to over 12,000 in cooking. It’s not clear why customer service-based courses aren’t being taken – hospitality management is offered at degree-level, so some people may opt for a degree instead of college classes. These programmes can also be difficult to access, especially in rural areas.

For many workers, there may also be an assumption that no education is needed for these roles, or that the time, cost, and effort in attending these courses isn’t worth it for whatever reason. They may also choose to participate in education for reasons other than gaining job-related skills.[2]

The education system and employers may also disagree on whose responsibility it is to teach certain skills. James Withers’ report on the skills delivery landscape in Scotland supports this idea – he notes that the educational system isn’t clear about which vocational skills are better suited to institutional learning and which are better suited to on-the-job or integrated learning.

The result is that businesses continue to struggle with their worker’s skills: if your workforce largely doesn’t participate in relevant education (or education at all), how can this skills gap be improved? How much on-the-job training can these businesses actually provide, given constraints in time, money, and staffing?

Schools are also left in a difficult position: how much can they prioritise for students who are taking these courses? Even if they cover all of the industry’s concerns, what are students likely to retain once they’ve completed their course? Are they failing the industry if they don’t provide course that students don’t take anyway?

Can anything be done about this?

There’s a clear mismatch between education and the skills required for may occupations in the hospitality industry. The majority of the hospitality industry falls under elementary or skilled trade occupations, which are not especially likely to participate in formal education. Missing skills primarily fall under soft skills, such as customer service and sales, but courses which meet these needs have relatively little uptake.

There isn’t a clear solution to this skill problem. All hospitality workers, even those with skills gaps, will have received some amount of on-the-job training. This may be the best solution to bridge this gap even further, although many businesses struggle to find the necessary time and resources. Some hospitality leaders mentioned that the government could provide support in the form of training support and materials.

Modern apprenticeships could also fill this gap, but the Scottish government prioritises funding for people under 25, which employers in our workshop felt does not reflect the reality of the industry. Survey data supports this sentiment – 70% of skilled and elementary workers that aren’t receiving education elsewhere are older than 24.[3] This group makes up the largest faction of the hospitality industry but isn’t able to receive this form of training.

In total, 70% of hotels and restaurants said that these gaps result in increased workloads for staff members. Businesses also struggle to meet quality standards, and struggle to update working practices or develop new practices.

This ultimately results in a vitally important industry that is suffering from large skills gaps and low educational attainment, along with high vacancy rates and high rates of in-work poverty, all of which compound to put tens of thousands of Scottish workers in a precarious situation.

Check out the full briefing and other reports from Serving the Future here.

About Serving the Future

Serving the Future is a three-year action research project working with hospitality employers and workers. The project is seeking to understand, reduce and prevent in-work poverty and identify changes that could be made within the sector. By working directly with employers and people with experience of low-paid work, the project is taking a variety of approaches to identify changes that can take place at an organisational level as well as necessary policy or systems wide changes that are required across Scotland. Serving the Future is funded by The Robertson Trust and is being delivered by the Institute for Inspiring Children’s Futures, the Fraser of Allander Institute and the Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship (University of Strathclyde), and the Poverty Alliance.

[1] Source: Author’s analysis of the Longitudinal Annual Population Survey, 2018-19

[2] This refers to the number of SCQF level 4-6 qualifications that were awarded in 2022. Some people may have achieved more than one qualification in cooking during this time frame.

[3] Source: Author’s analysis of the Annual Population Survey, 2019-20

Authors

Allison is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in health, socioeconomic inequality and labour market dynamics.