Next week sees the publication of the latest Government Expenditure and Revenue (GERS) report.

In this second blog, we outline what you can expect to see in the numbers and what they might mean for wider debates on Scotland’s public finances.

What will the GERS numbers show?

GERS covers a wealth of information about Scotland’s public finances – including how much we spend on particular government services and where the main sources of revenue come from.

This year, the statisticians have been consulting on how to present Holyrood’s new tax powers.

But the focus will no doubt be on the headline numbers.

It’s unlikely that they will make pretty reading – here are last year’s numbers.

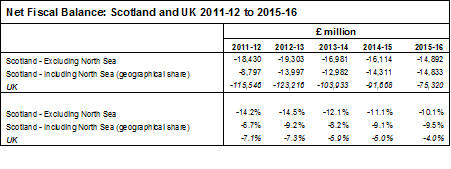

The 2016 GERS report showed a net fiscal balance in Scotland of -9.5% (including a geographical share of North Sea oil) for 2015-16. This compared with a UK balance of -4.0%.

As a rule of thumb, assuming that existing debt levels are manageable, most economists would be wary of a net fiscal balance to GDP ratio being much than -3% on a regular basis.

This year we are likely to see a similar relative gap – albeit both the Scottish and UK figures will improve.

There’s a simple reason for this weaker relative performance and that’s the fall in oil revenues from around £11bn in 2011-12 to virtually zero. Back in 2011-12, according to the GERS methodology, Scotland was in a stronger relative position.

Even though oil production has been growing recently the government is raising very little (if anything) in revenues.

Why?

Firstly, the oil price is about half that in 2014.

Secondly, tax rates have been cut to help support the sector through the current challenges.

Thirdly, production is increasingly concentrated in costly areas so profit margins are squeezed.

Finally, as many fields start to be decommissioned, producers can offset the costs associated with cleaning up old oil and gas installations against their tax liabilities.

Unfortunately, this isn’t likely to change any time soon.

A BRIEF ASIDE

Work with us

We regularly work with governments, businesses and the third sector, providing commissioned research and economic advisory services.

Find out more about our economic analysis consulting.

What’s the outlook like?

The GERS methodology doesn’t really change very much year on year.

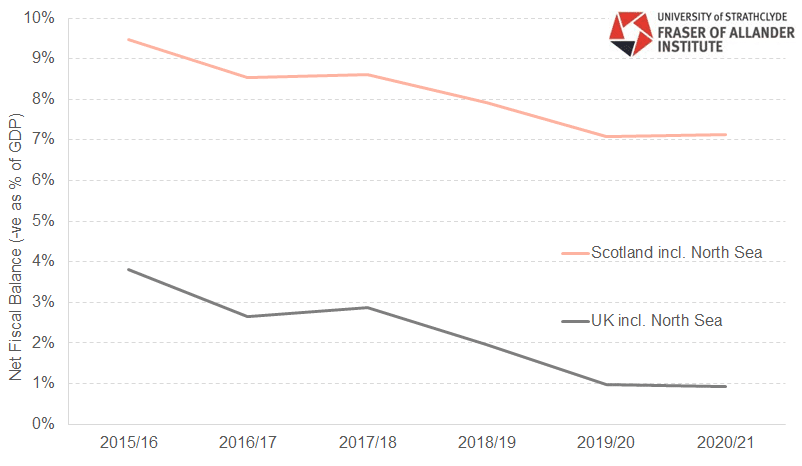

Therefore, it’s possible to project Scotland’s estimated net balance based upon the OBR’s latest forecasts for the UK economy and public finances.

The UK remains in a challenging fiscal position. Numerous targets to eliminate the deficit having been discarded or pushed back.

But unless there is a dramatic turnaround in oil revenues, Scotland’s net balance – based upon the GERS methods – is projected to be weaker than the UK position going forward.

Source: FAI projections based upon latest OBR forecasts (assuming Scottish revenues grow in line with per capita UK growth adjusted for Scotland’s population; OBR oil and gas forecasts with Scotland retaining geographical share; and, Scotland retains share of UK expenditure by individual component)

Why does the GERS methodology show Scotland having a larger negative net fiscal balance than the UK as a whole?

There are two reasons.

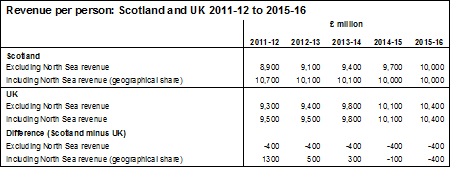

Firstly, according to the GERS methodology Scottish tax payers raise slightly less per head than the UK average – in the latest year this was equivalent to £400 per head.

This isn’t surprising. Although Scotland’s GDP per head is broadly in line with the UK, once you factor in the City of London’s predominance in raising corporate and wealth taxes and that we have fewer people at the top of the income distribution where lots of taxes are raised, a marginally lower figure makes sense.

Scotland isn’t unique in that regard – most areas of the UK are in a similar position. Indeed only London, the South East and the East of England are estimated to raise more per head than Scotland according to the ONS.

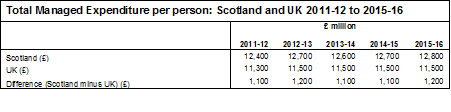

Secondly, spending per head for Scotland is quite a bit higher than for the UK – a difference of around £1,200 per head in 2015-16.

Again this is not that surprising.

We know that Scotland spends more per head than the UK both because of how much is spent on things like health, education, economic development etc. but also our slightly higher number of people entitled to benefits associated with issues such as long-term ill health etc. There are also some minor technical issues, like the fact that Scottish Water is a public asset in Scotland but not elsewhere.

There is nothing to suggest that these trends will have changed for 2016-17.

What does GERS tell us about the constitutional debate?

As pointed out yesterday, GERS takes the current constitutional settlement as given. It doesn’t pretend to do anything more or less.

If the very purpose of more autonomy is to take different choices about the type of economy and society that we live in, then a set of accounts based upon the current constitutional settlement and policy priorities will tell us little about the long-term finances of an independent Scotland.

Similarly, independence will bring with it new macroeconomic risks and opportunities that will need to be managed. These, in turn, will have an important bearing on Scotland’s long-term public finances.

GERS also doesn’t tell us about what the financial costs, risks or savings of implementing a new constitutional framework might be. And it doesn’t tell us how faster (or slower) growth could impact on the results in the future.

What next week’s GERS will do is provide a pretty accurate picture of where Scotland is in 2016-17. And it will provide a useful insight into where our money is spent each year, who spends it and where it comes from.

In doing so, it sets a useful starting point for a discussion about the immediate choices and challenges that need to be addressed by those advocating new fiscal arrangements.

In this regard, there is no escaping the fact that the GERS numbers paint a difficult picture. It is simply not possible to operate under independence with budget numbers like this on a consistent basis.

This means that in pursuing the case for independence, the Scottish Government need to set out the tough choices that it would make alongside a detailed and comprehensive plan for how it would manage the public finances with responsibility for both sides of the balance sheet.

This won’t be easy, but is absolutely crucial.

Final thoughts

In summary, all countries face big fiscal challenges in terms of what will replace declining revenues in the face of rising spending pressures. Changing the constitutional set-up doesn’t alter the fact that these fiscal challenges need to be addressed by all governments in all countries.

But a more autonomous Scotland will be forced to meet such challenges sooner rather than later.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.