This blog shows that council tax rates are now markedly lower in Scotland than in England and Wales. Increasing council tax in Scotland to match rates in Wales (or England) would raise substantial revenues, but would have adverse distributional implications. On balance, the case for more fundamental reform of property taxation would appear much stronger than the case for increasing rates within the existing system.

Differences in income tax policy between Scotland and rUK have been the subject of heated debate. There has been relatively little attention paid to differences in council tax policy in Scotland compared to England and Wales. But in some ways, the differences in council tax policy are more pronounced than they are for income tax.

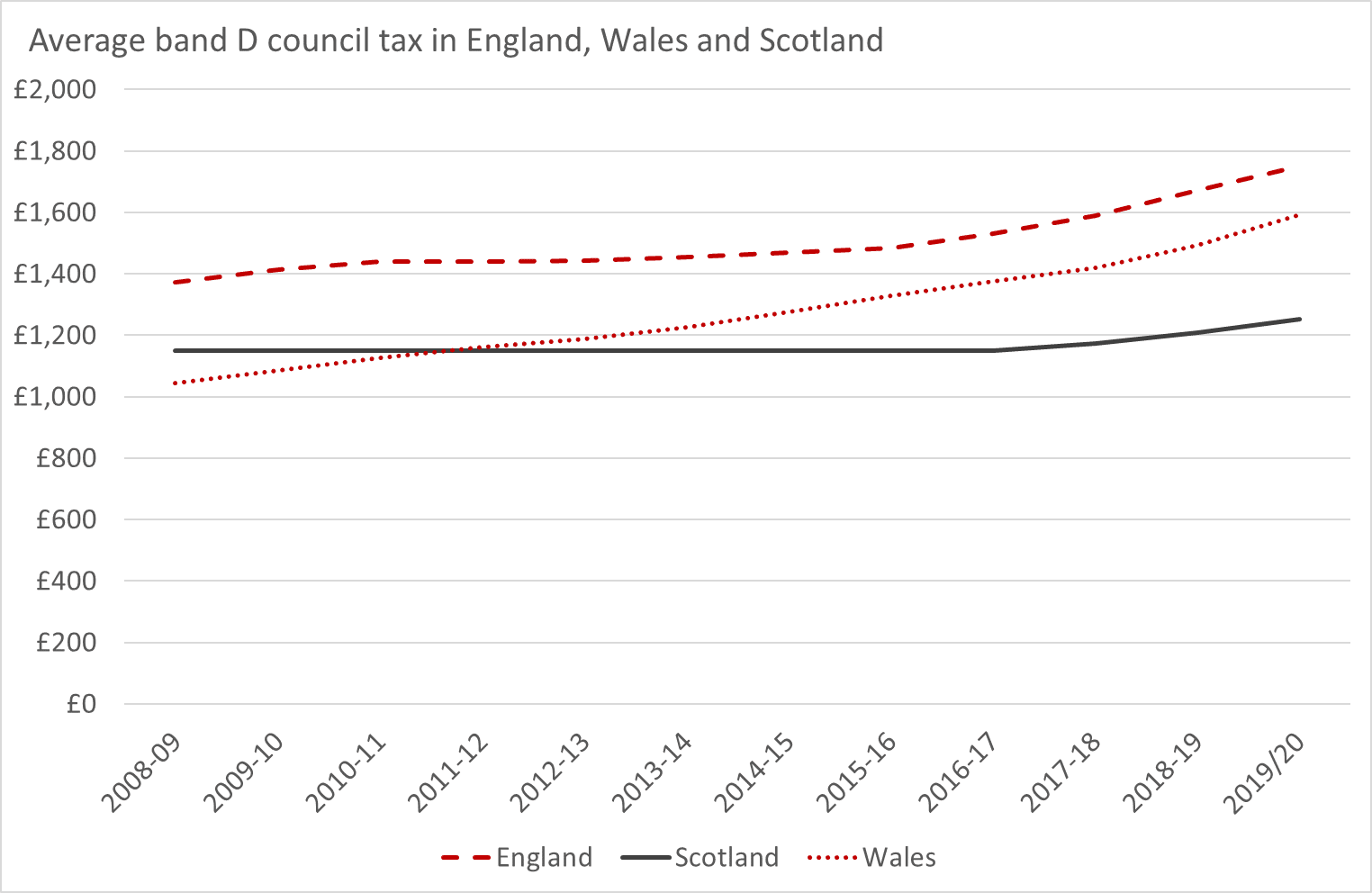

Back in 2008/09, the average band D council tax in Scotland was around 10% higher than the average band D charge in Wales, and 16% lower than the average in England.

As a result of the nine year council tax freeze in Scotland, Council Tax north of the border for the average band D house is now some 14% lower in real terms in 2019/20 than it would have been had it kept pace with inflation.

In contrast, average Band D levels in England in 2019/20 are around the same in real terms as in 2008/09, following several years of above inflationary increases recently. In Wales there was no freeze and instead council tax is now 20% higher in real terms than in 2008/09.

By 2019/20, average band D council tax in Scotland is 21% lower than in Wales and 28% lower than in England (Chart 1).

These are significant differences in tax rates, but what is the implication for revenues?

Matching Welsh band D levels would raise around £600m for the Scottish budget in net terms (i.e. after taking into account the rise in expenditure on Council Tax Reduction that would be required to protect low income households from the tax increase). Matching English tax rates would raise around £900m additional revenues.

Of course, whilst these hypothetical scenarios give an indication of the revenues that the Scottish budget has potentially foregone as a result of the historic freeze, there are good grounds for not implementing such increases.

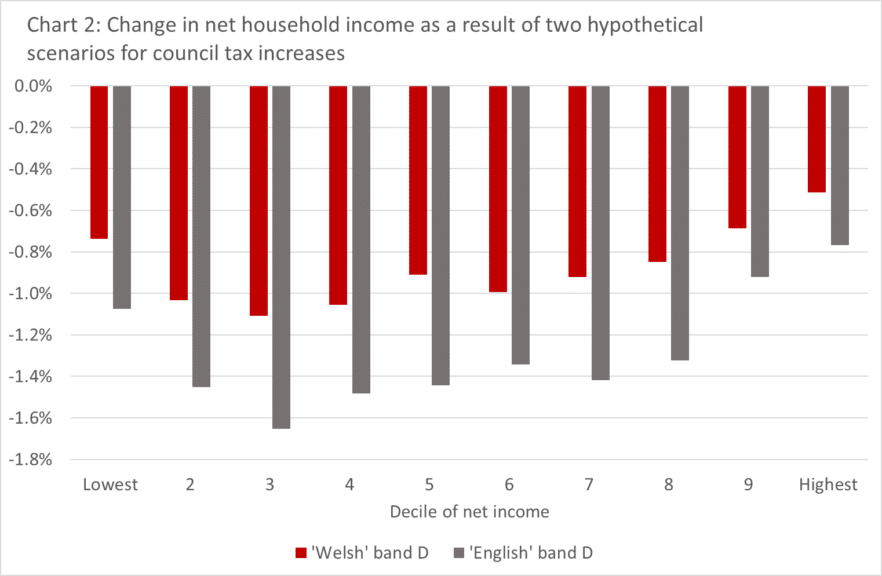

The narrow spread of council tax bands (and the absence of any revaluation exercise since 1991) means that the relationship between property value and council tax is weak – without wider reform, lower value properties would face proportionately larger tax increases than better off properties.

Furthermore, the relationship between council tax band and income is also weak, meaning that council tax increases – without wider reform – would be regressive rather than progressive (Chart 2).

But rather than making the case for inertia, what this illustrates is the critical importance of considering wider reform of the system of property taxation. Many would argue that there is scope to raise revenue from property taxation, but only if the fundamental flaws in the existing system are addressed.

The announcement, as part of the 2019/20 budget deal, of cross party talks on a replacement for council tax – with legislation published by the end of this parliament – is a welcome first step in this direction. But we have been here before. The case for reform is well understood. It remains to be seen whether this next review will catalyse meaningful change in a way that the Burt Review of 2006 and the Commission on Local Tax Reform of 2015 could not.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.