Anna Murray & Graeme Roy, Fraser of Allander Institute, Department of Economics, University of Strathclyde

The uncertainty over Brexit has dominated much of the debate in Scotland in recent weeks. This will undoubtedly remain the case in the months (and years) ahead.

It’s easy to forget that in just under eight months, the Scottish Parliament will start taking responsibility for a raft of new fiscal powers.

The debate will no doubt continue over whether these powers go far enough or are the right levers to be devolved. Nevertheless compared to previous administrations, the policy toolkit available to the new Scottish Government will be unparalleled.

In the months ahead, we’ll return to discuss the range of possible options to use these powers – including at our new annual Scottish Budget event in September.

What has been striking however, is that much of the debate so far – particularly during the recent Scottish elections – has centered upon rather narrow questions such as how much revenue can be raised from higher income tax rates or the cost of a more generous welfare pledge. Indeed on many occasions the entire focus has seemingly been to rank parties according to their tax raising credentials and generosity of their spending commitments.

The debate has yet to move seriously into the realm of growth or long-term fiscal sustainability.

This is rather odd. One of the key objectives of the Smith Commission was to quite deliberately tie a much greater proportion of future Budgets to tax revenues and, by implication, the overall performance of the Scottish economy.

Around 40% of ‘devolved expenditures’ will now be funded by tax revenues collected north of the border – a figure that will rise to 50% once half of VAT revenues are assigned to Holyrood.

This means that a greater debate is needed, not just around simple comparative statistics, such as how much 1p on income tax would raise or the cost of a £50 increase in winter fuel payments, but on the overall approach of the Scottish Government to promoting growth, tackling inequality and fiscal sustainability.

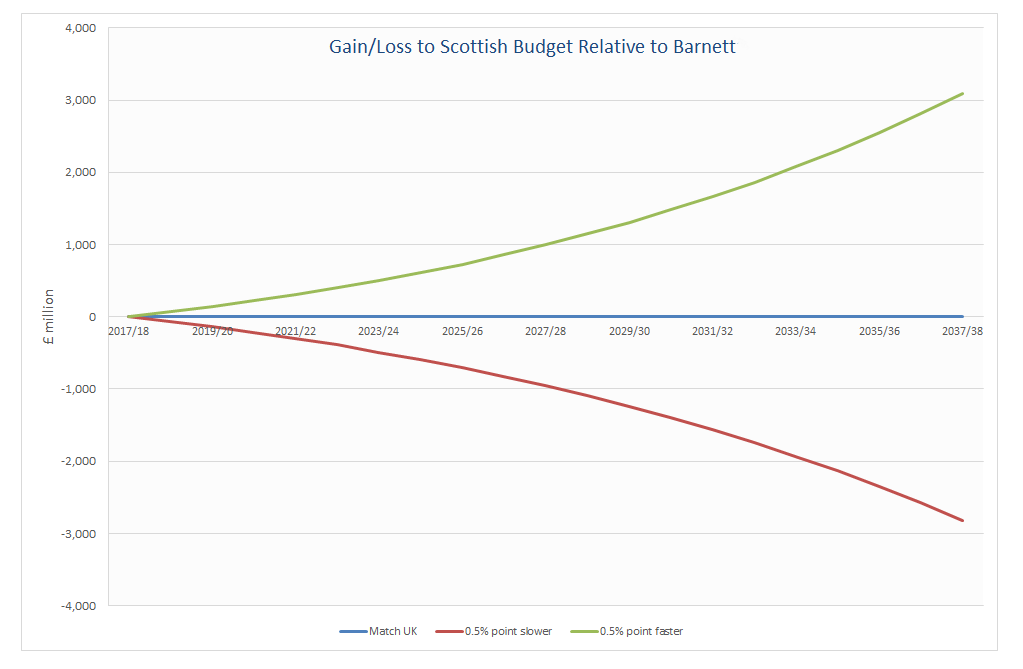

Under the new Fiscal Framework, Scotland’s Budget will effectively be no better or worse off provided we can match the growth in equivalent tax receipts (and welfare) in the rest of the UK.

If not, then the amount we will have to invest in public services will fall.

Of course, the effect is symmetrical so that if we outperform the rest of the UK we will have more to invest than we would have had compared to Barnett.

What is not widely understood is that the scale of the transfer of powers to Scotland under Smith means that small variations in economic performance will, over a relatively short period of time, have significant implications for public spending.

As an illustration, if Scotland’s per capita growth receipts were to lag the UK by just ½ a percentage point, over ten years that would equate to a drop of around £1bn in revenues each and every year thereafter – far outweighing any of the current tax or proposed spending commitments.

This transfer of risk and reward is exactly what Smith intended to achieve. But with it comes the imperative that any discussion over how much we can spend on public services starts from a robust discussion about growth and fiscal sustainability. It also means that effective government policy can’t just be about individual tax and welfare policies, but instead needs to be a coherent strategy which encompasses the entire £40bn of devolved expenditure and £20bn of devolved taxation.

Recent developments in the Scottish economy set a challenging backdrop. Scotland’s economic performance has lagged that of the UK over the last year, not just in overall growth but also per head. As David Eiser points out here, the impact of Brexit on Scotland’s relative economic performance is unclear, with opportunities to outperform but also risks to lag behind the UK.

In addition, as we will discuss in a subsequent blog, there are a number of structural challenges embedded in the fiscal framework – whether that is the impact of London house prices on future Stamp Duty revenues, the impact of personal allowance increases on tax revenues in Scotland or our shrinking working age population – that will make matching tax growth per head in the rest of the UK a challenge in the years ahead.

If this sounds pessimistic then this is not the intention. It’s simply to highlight the even greater importance that now exists in placing a strong, inclusive and fiscally sustainable economy at the heart of all policy debates – from higher education research funding, the review of enterprise agencies, local government reform and crucially, the potential opportunities from a decisive switch to preventative spend.

And there are significant opportunities. The ability to use a much wider suite of economic tools to create a more prosperous economy is there to be taken advantage of.

On welfare, an approach that treats individuals with respect and provides them with the opportunity to maximise their economic potential will only help improve Scotland’s long-term growth potential and public finances.

There is also now greater opportunity to join up policy responses. With the transfer of employability powers for example, comes the opportunity to deliver a much more coherent package of support for those out of work (and at threat from being out of work) which encompasses Scotland’s entire school education, higher & further education, training, skills, apprenticeship and enterprise policies.

And on taxation, policies to balance growth with revenue generation – whilst always being mindful of the potential implications for behavioural change or tax avoidance – will boost sustainability.

None of this will be easy – and business in particular needs to find a stronger voice and analytical capacity to contribute to such debates – but by openly discussing these issues we will serve Scottish public services and the people that rely on them much more effectively than if we limit ourselves to short-term parochial debates over the cost of 1p on income tax or £50 on Winter Fuel.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.