When is a Chancellor statement to the House of Commons a “major fiscal event”? The latest iteration of the Charter for Budget Responsibility says that:

To support economic stability, the government is committed to the principle of holding one major fiscal event a year, unless in the case of an economic shock

Definitions of what might constitute an economic shock for these purposes are thin on the ground, which is of course unsurprising – as we wrote at the time, no Chancellor could credibly commit themselves to not intervening if their judgement was that it was required.

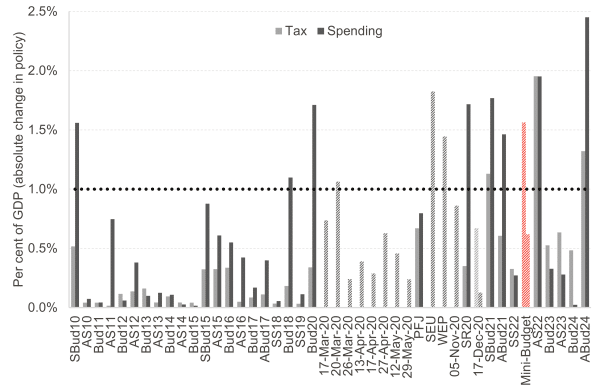

The definition of a major fiscal event is also absent by itself. One could apply the threshold set for fiscally significant measures, defined as 1% of GDP. But that seems much too high, implying that many years since 2010 had no major fiscal events, which is obviously untrue.

Chart 1: Major fiscal announcements since the OBR was created, with shaded bars indicated cases where a forecast was not released concurrently

Source: OBR, FAI analysis

Of course, the Chancellor could have committed herself to not changing anything, even if it meant that the fiscal rules were broken (more on this later) and just wait until the next Budget. That would be a credible signal of commitment to the principle of a single fiscal event, because it would come at a cost – in this case, potential political exposure.

But all the talk in the papers suggests that several billion pounds’ worth of cuts from disability and incapacity benefits will be made to meet the fiscal rules. That suggests that:

- This is in fact a major fiscal event, because it looks and feels like one: the Chancellor commissioned a forecast and is set to announce large policy changes. If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

- The Chancellor is therefore failing to stick to her promise to only hold one major policy event a year at the first hurdle.

- And most worryingly, she is scrambling to meet her fiscal rules come what may, instead of (i) running too close to the line to begin with and (ii) whether or not it is desirable. Fiscal rule derangement syndrome is alive and well.

Why are we in this position?

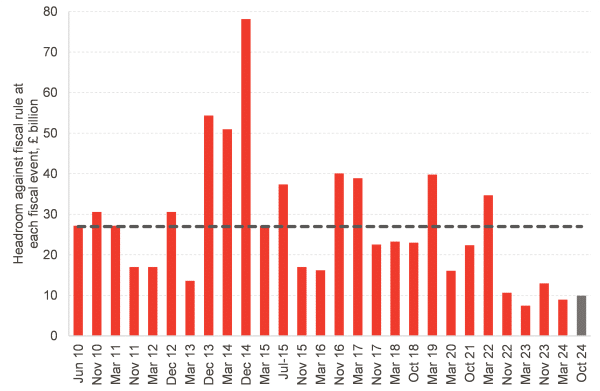

When the Office for Budget Responsibility published its assessment of the Autumn Budget, the chart below was perhaps the most striking. Even after making the fiscal rules a lot less stringent than previously (and Jeremy Hunt’s weren’t the strictest to begin with), Rachel Reeves had the third-least headroom since the OBR was created, and just over a third of the average since 2010.

Chart 2: Headroom against meeting the main fiscal rule since 2010

Source: OBR. Values calculated in terms of 2029-30 GDP forecasts for comparability

In layperson’s terms, this is leaving oneself hostage to fortune. Long-term gilt rates are about 0.8 percentage points higher than at the time the OBR took determinants for their October 2024 forecast, which according to their ready-reckoner would completely wipe out the headroom the Chancellor had.

Is it the Chancellor’s fault that gilt rates have gone up? No. But it is her responsibility to plan for that eventuality, and weigh up how likely it is that a negative shock will come to pass – and how prepared she is to run a high probability risk that it will break her rules.

A changed world – so are tax promises still credible?

The UK Government has not been shy in claiming that the world has changed in the last few weeks. National defence spending is going up, much of it is though as-yet unfunded promises. The one-off injection in the level of public spending announced in October now seems likely to be followed by subsequent real-terms freezes or cuts for most departments, who are being asked for pretty steep ‘efficiencies’ as part of the Spending Review.

Many of the pressures coming down the track – not only on defence, but also on ageing – are recurring spending, which means that they will add to the structural deficit all else equal, and therefore cannot simply be wished away or borrowed for indefinitely.

Given that the Chancellor has – as many of her predecessors – shown herself unable to withstand not meeting her fiscal rules at an official OBR forecast, the prudent course of action would be to set fiscal policy in such a way that there is enough buffer to avoid making questionable decisions solely for the purpose of meeting those rules. Ideally that would have meant a larger buffer in the Autumn, as we argued back in January.

But we are where we are, and the question is then how credible it is that the Treasury can force through a pretty unpalatable set of departmental and disability benefit cuts, thus relying entirely on the expenditure side of the ledger. It is of course a perfectly politically valid choice, but one that is strange both given the Government’s political leanings and the fact that it continues to ignore a whole other avenue of policy, which would be to raise taxes. There have been some rumours that the threshold freeze may be extended back to the end of the forecast, although that is a very untransparent and inefficient way of raising taxes.

Ultimately, the UK Government appears hamstrung by its promise to not raise the rates of income tax, employee NICs, VAT or corporation tax. Put together, they account for the vast majority of revenues, and any solution that avoids relying only on spending cuts must grapple with the fact that public sector current receipts are not some exogenous property of a country, but rather a policy instrument to deliver an acceptable level of borrowing and debt for a given level of desired public services and national security. The sooner the Government wakes up to this, the faster we can move on to discussing specifics instead of dancing around the inevitable truth.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.