We have recently started a new year-long project to examine how patterns of weekly hours worked have been changing in recent decades, examine what factors help explain those trends, and to consider implications for poverty, inequality – and policy. Whilst the distribution of hourly pay receives a lot of attention as a metric and for the design of policy, the level and distribution of hours worked is just as important for issues as diverse as poverty rates to tax revenues.

The project is funded by the Standard Life Foundation. Although the project was conceived well before the Covid-19 epidemic took hold, we plan in due course to examine how working patterns are changing during the pandemic and (hopefully) the recovery. But in the meantime it is useful to consider what has happened in recent years. Past trends may shed light on how the labour market might respond to current and future economic shocks and policy responses and help us identify who is most exposed to challenging outcomes.

We plan to share some of our findings as they emerge. In the first of such articles, we outline some of the changes to male working hours over the past 25 years across the UK. Subsequent analysis will consider trends for females (who have experienced quite different trends) and at the level of households, as well as individuals. What do we find?

In 2010, men worked 5-6% fewer hours per week than they did 15 years previously

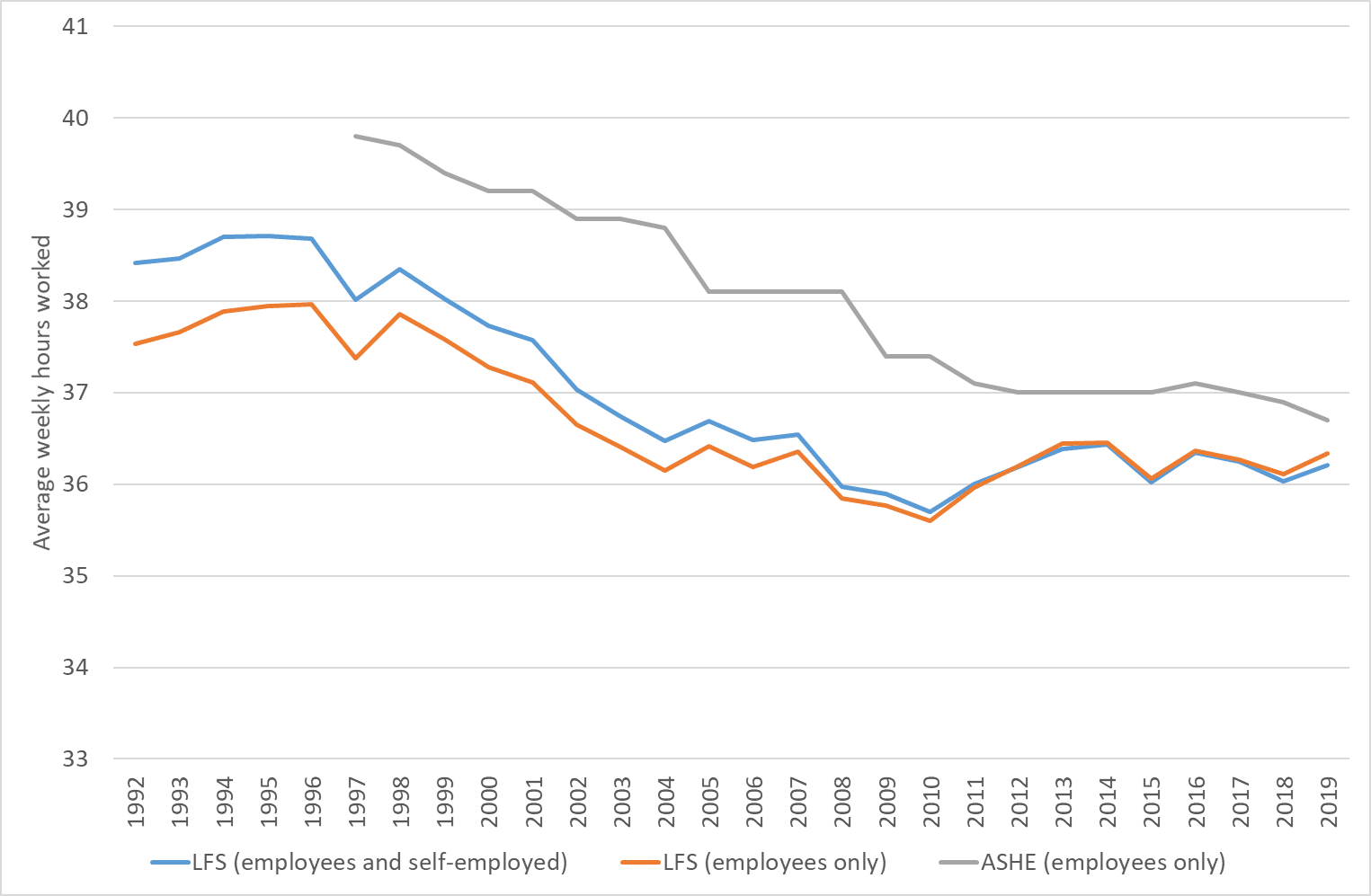

Between the mid 1990s and 2010, the average hours worked by males declined quite consistently (Chart 1). According to the LFS, average hours worked by male employees declined by 1.8 hours (almost 5%). According to ASHE, average hours worked declined 2.4 hours per week, a decline of 6%.

Since 2010, this decline in hours has slowed according to the ASHE, or reversed slightly according to the LFS.

Chart 1: Average hours worked weekly by males in the UK

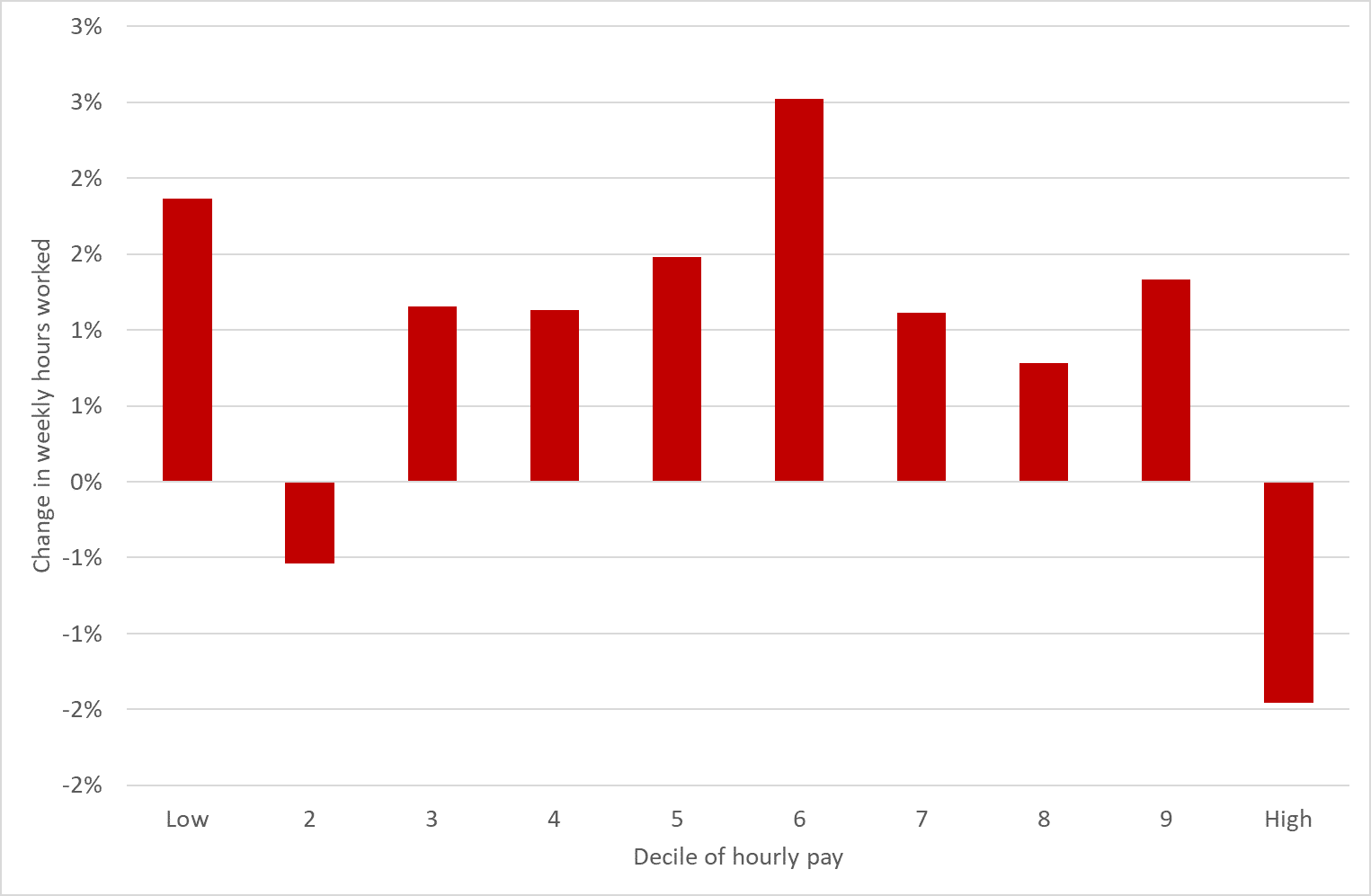

But low-paid jobs have seen much larger falls in average hours worked than higher paid jobs

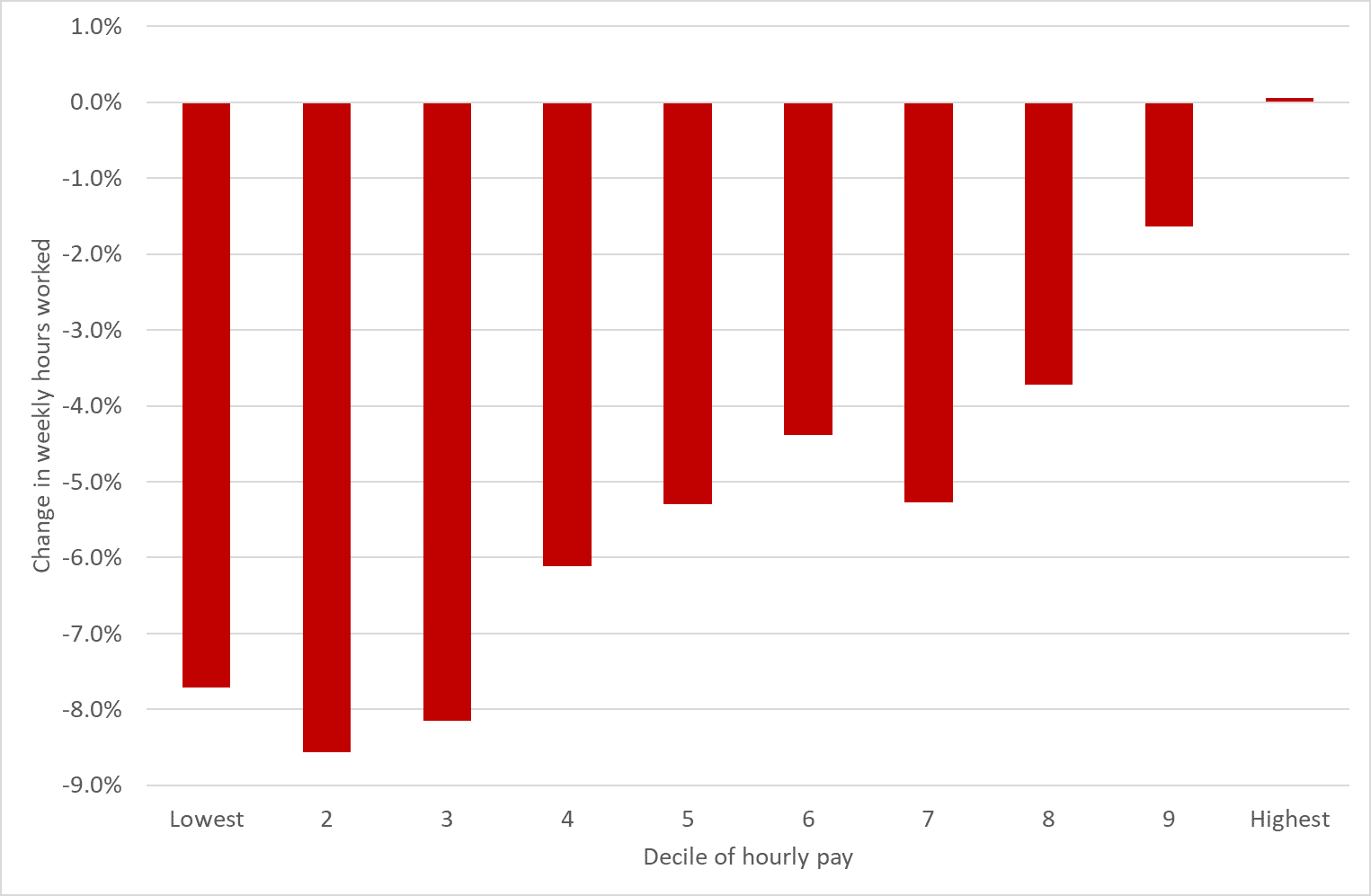

However, the fall in average hours worked until 2010 masks substantial variation in hours changes across the distribution of hourly pay. Low-paying jobs have been associated with much more significant declines than more high-paying jobs.

This observation is shown in chart 2. Each year, male employees are grouped into ten deciles of hourly pay – with the lowest-paid 10% in decile one, through to the highest paid in decile 10. Between 1994/5 and 2009/10, average hours worked by the lowest paid 30% of workers declined by around 8%. Average hours worked by those in hourly pay deciles 4 declined by 6%. For those in deciles 5-8 the decline was 4-5%. Decile 9 saw decline in hour worked of 1.5% whilst the top decile saw hours worked unchanged.

It is worth noting that the trends shown here (and in the rest of the analysis in this article) are derived from the LFS. Similar analysis from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) reveals a steeper gradient between decile of hourly pay and change in hours worked, with declines in average hours exceeding 10% for the bottom deciles. Unfortunately, we are not currently in a position to be able to present the ASHE data publicly (ASHE data is deemed potentially sensitive, and analysis based on it is only released for publication once the statistics authorities are satisfied that the analysis is not ‘disclosive’; but these processes have been suspended during the Covid19 crisis).

One might query whether the pattern in Chart 2 simply reflects the choice of 2009/10 as the year of analysis, and is showing the cyclical impact of the recession. But the trends are very much structural over the period to 2009/10, as has been documented by others (e.g. Belfield et al. 2017)

Chart 2: Change in average weekly hours worked by decile of hourly pay, males, 1994/5 – 2009/10

This trend had profound implications for earnings inequality and levels of in-work poverty

The trend for hours worked to fall more amongst men working in low-paid jobs than amongst men working relatively high-paid jobs has profound implications for male earnings inequality. Between 1997 and 2010, the 90:10 ratio of hourly wage inequality amongst men (i.e. the ratio of the wage of someone at the 90th percentile of wages relative to a worker at the 10th percentile of wages) increased by 5%. But the 90:10 ratio of weekly earnings inequality amongst men increased by 24%.

The trend for average working hours in low-paid jobs to decline more than in higher paid jobs over the period to 2010 is not specific to particular age groups, household types; nor to a rise in second jobbing…

One might hypothesise that the patterns described for male workers reflect changes in working patterns among specific demographic groups. Perhaps the fall in hours worked in lower paying jobs reflects greater levels of part-time working by the young while studying, or by older workers making a more graduated approach to retirement. But our analysis shows that this is not the case. The pattern of changes in working hours by hourly pay decile is common to prime age males as well as to the young and the old.

One also might wonder whether the trends are more prevalent amongst males in particular household types. If the trend was stronger amongst single males, or males in households with a second earner, or males in households with children, this might provide clues about what factors influenced the trend (for example, do the trends reflect supply-side responses to changes in welfare design). But our analysis finds that the trends are broadly common to men in different household types.

The analysis described above shows patterns of hours worked in peoples’ main job. It might be hypothesised that the trend reflected a rise in the number of men in low-paying jobs who have a second job. (In other words, the apparent disproportionate fall in hours worked in some men’s main jobs might imply be offset by a rise in hours worked in other jobs). But our analysis finds no evidence that the proportion of low-paid men working in second jobs has increased (nor that the average hours worked in second jobs has changed).

Falls in hours worked are mainly accounted for by a fall in paid overtime and a rise in part-time working

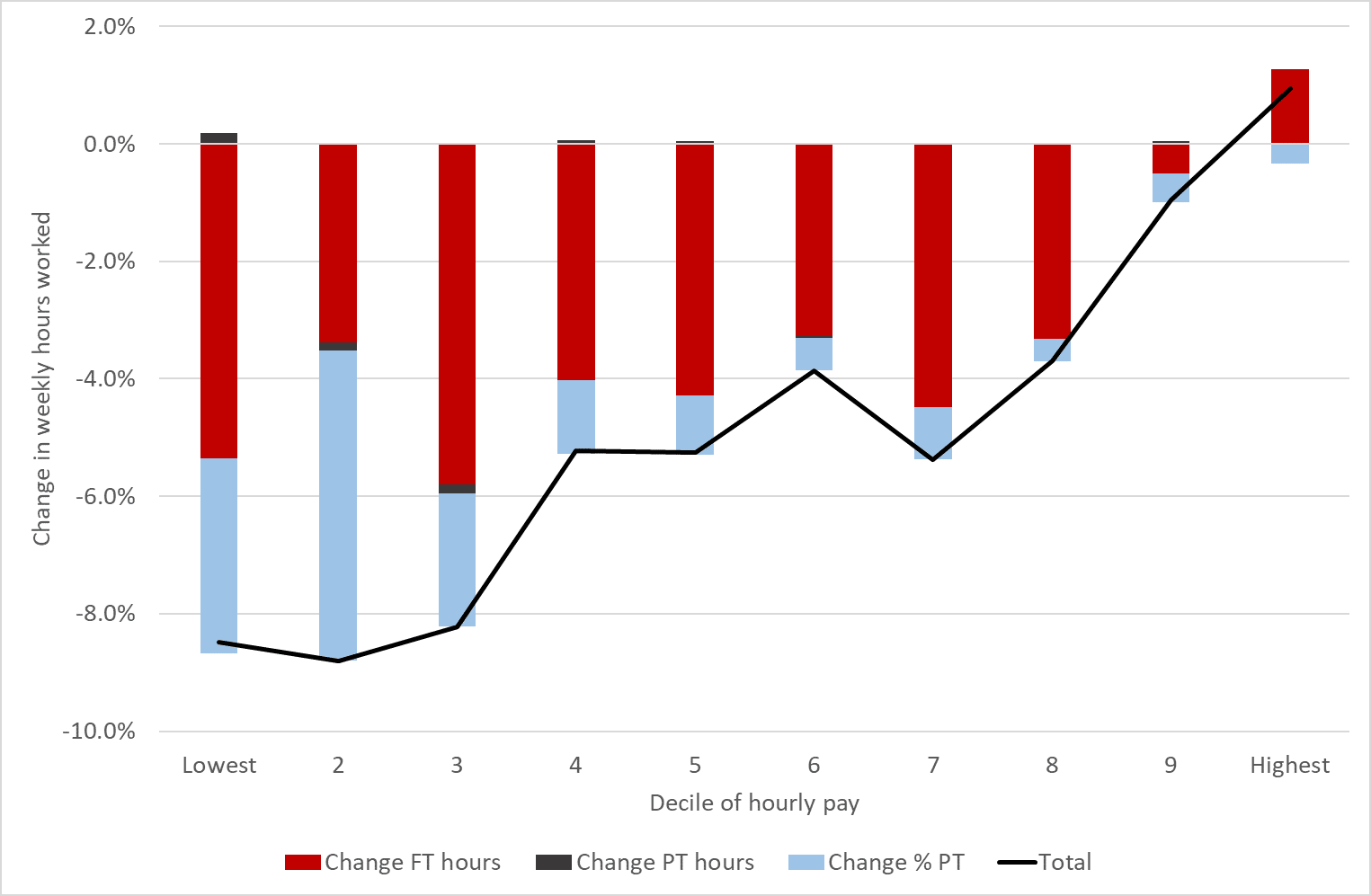

A fall in average hours worked could reflect one of several factors (or a combination of them). It could reflect:

- A rise in the proportion of employees working part-time rather than full-time

- A fall in the average hours worked by full-time workers

- A fall in the average hours worked by part-time workers

Our analysis shows that falls in FT hours account for a large proportion of the overall decline in average hours worked, and that an increase in the proportion of men working part-time accounts for a sizeable proportion of the reduction in hours worked in the bottom two deciles of jobs ranked by pay (Chart 3).

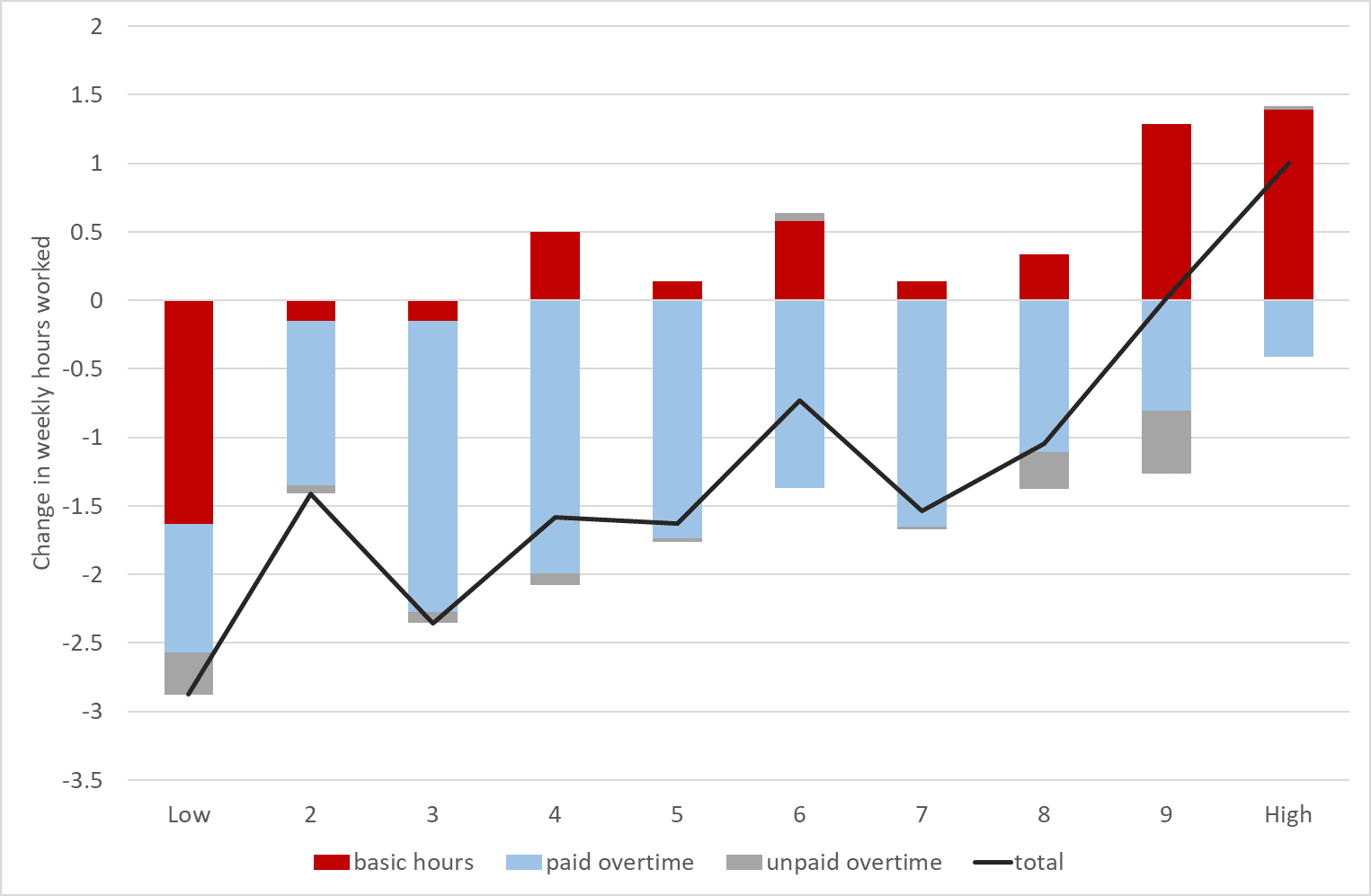

Furthermore, the decline in hours worked by full-time workers can largely be accounted for by reductions in the amount of paid overtime undertaken, rather than a decline in standard hours. The exception to this is in the bottom decile of jobs ranked by pay, where standard hours have also fallen (chart 4).

Chart 3: Factors contributing to change in average hours worked by decile of hourly pay, 1994/5 – 2009/10 (prime age males)

Chart 4: Changes in weekly hours worked by full-time workers: components of change 1994/5 – 2009/10 (prime age males)

What about the post-2010 period?

We’ve spend a lot of time talking about the period leading up to 2010, but what’s happened since then is quite different. Average hours worked have remained largely unchanged. Furthermore, there is a much more consistent story across the distribution of hourly pay (chart 5); and perhaps some evidence of an unwinding of the changes in the previous period. Changes in standard hours account for the lion’s share of the changes described in Chart 5, apart from in decile 1 where an increase in full-time over part-time working is the dominant explanation.

Chart 5: Change in average weekly hours worked by decile of hourly pay, males, 2009/10 – 2018/19

But trends in underemployment do not seem very strongly correlated with trends in hours worked.

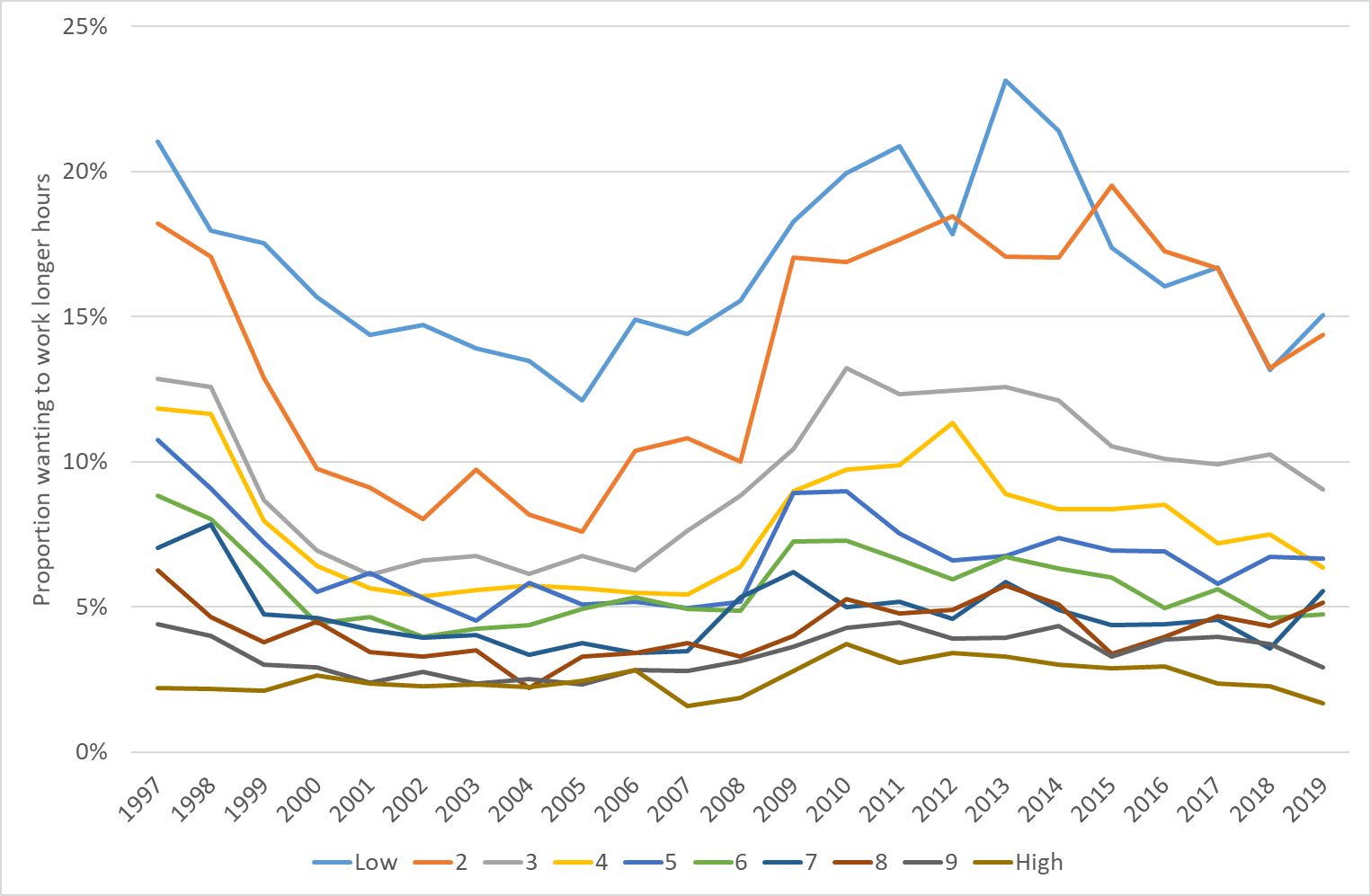

Recently there has been a lot of concern about underemployment, the idea that some people in employment may not be able to work as many hours as they would like. There are a number of different ways of measuring underemployment. One of the simplest is to consider what proportion of those in employment say they would like to work longer hours at their current basic rate of pay, if they had the opportunity.

Underemployment is consistently higher in low-paid jobs. What about changes in underemployment over time? If the reductions in average hours worked are largely involuntary, one might expect that rates of underemployment would increase as average hours decline.

However, underemployment declined relatively rapidly during the late 1990s and early 2000s (chart 6) – coinciding with the period when average hours worked were declining, with this decline in underemployment being particularly prevalent in the lower deciles of hourly pay (which saw the largest declines in average hours).

Underemployment began increasing in the bottom three deciles from the mid-2000s, and increased sharply in 2009, remaining elevated until it began declining again in 2014.

So underemployment seems to have fallen most when hours worked were falling, and increased in the post 2010 period when hours worked were static. This perhaps reflects that underemployment responds to changes in disposable income rather than hours worked specifically – and issue worthy of further investigation.

Chart 6: Proportion of prime age males wanting to work longer hours at current basic rate of pay, by decile of hourly pay

Conclusions and next steps

This article gives a flavour of the issues we will be investigating throughout this Standard Life Foundation funded project.

We will of course be extending the descriptive analysis above in a variety of ways. This will include looking at trends for women as well as men, and considering how trends in individual working patterns have implications at household level. We also hope to examine the importance of rising precariousness of hours for underemployment, and we’ll also be looking at changes by industry and occupation.

We’ll also be looking in further detail at what might help explain some of the trends described here. The observations described– including the very uneven pattern of hours reductions prior to 2010 and the break in that trend since then – already pose some interesting issues to investigate, especially when overlain with trends in underemployment.

Potential explanations for reductions in hours worked – particularly among low-paying jobs – in the period to 2010 include structural change (away from industries/occupations typically associated with long hours), real terms increases in the minimum wage which can have supply and demand side responses, a rise in non-typical contracts such as zero-hours contracts, the design of welfare systems to encourage work over non-work, and a variety of explanations for the decline in overtime relating to weaker worker bargaining power combined with firms’ pursuits of greater efficiency.

The cessation of the trend of falling hours since 2010 supports the hypothesis of Bell and Gardiner (2019) that the UK’s flexible labour market has enabled households to increase the supply of labour on the intensive margin in response to the fall in real wages (albeit that low-income workers have not been able to increase their labour supply as much as they would like).

These and other issues we will investigate during the remainder of the project – please do get in touch if you have views about which elements of this story you think are particularly worthy of examination.

Authors

David Eiser

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.

Mark Mitchell

Mark Mitchell is a former research associate at the FAI. In 2021, Mark moved to a post in the Competition and Markets Authority. His research area is applied labour economics, focussing on the causes and effects of human capital accumulation over the lifecourse.