The fourth budget of this parliamentary term has, as expected, led to a healthy increase in the resources available to the Scottish Government.

So what were the key points from today?

The overall outlook for public spending

Spending on public services is up by around 3.6% in real terms in budget 2020/21 compared to budget 19/20 – excluding new responsibilities on social security and farm payments.

This uplift is nearly all due to increases in the block grant as a result of Barnett consequentials flowing from spending increases by the UK Government. Arguably, not quite all of this uplift represents an increase in actual spending power – some of it reflects funding implications of higher pension costs for public bodies.

But nonetheless this is the largest increase in the block grant since pre-austerity days. The block grant is now just under 3% lower than in 2010/11.

As well as increases to the block grant, the Scottish Government has also chosen to maximise spending in 2020/21 by using its new resource borrowing powers to mitigate the effect of forecast error that it knew were coming down the line.

Recall, the budget faced a £200m reconciliation this year to reflect the fact that the 2017/18 budget was based on a set of income tax forecasts that subsequently turned out to be too optimistic. But rather than meeting the costs of that reconciliation in 2020/21 they have chosen to borrow, meaning that the next Scottish Government after the election will have to repay the money.

The expected reconciliation for next year has become slightly less negative – now around £550 million – but is still a very large future risk to be managed.

The outlook for earnings – which underpins the forecasts for income tax – has improved marginally since the SFC’s last assessment in May. As a result, the outlook for tax revenues is also now slightly better than might have been anticipated 6 months ago.

But the overall economic outlook remains weak.

The budget effects of the Scottish tax policy – which raises over £500m more in revenues for the government than if UK policy were implemented – has been all but wiped out by weaker earnings growth in Scotland in the past couple of years, and there is nothing in the forecasts to suggest any bounce-back in the next few years.

The budget for capital spending is also up significantly – the block grant from Westminster is increasing by 12% in real terms. On top of this, the government plans to make full use of its capital borrowing powers in 2020/21. This will take capital investment in real terms back to its pre-austerity peak.

Tax Policy

The Scottish Government chose to once again freeze the tax threshold for the higher rate, which will, as earnings rise, take more people into the Higher Rate band.

Kate Forbes said “To cement the progressivity of our tax system, we will increase the Basic and Intermediate Rate Thresholds by inflation to protect our lowest and middle earning taxpayers.”

There is a somewhat technical point of interpretation behind this that may cause confusion.

What the Scottish Government are not doing is increasing the individual thresholds for the Basic and Intermediate rates by inflation – which is perhaps the normal way people would interpret this statement.

Instead, they are increasing the gap between both thresholds and the Personal Allowance by inflation.

The difference between the two approaches is marginal for individuals in one year. But it does mean that the individual thresholds are increasing by less than inflation.

This won’t win any plain English communication prizes: understandably, it is being widely reported wrongly.

Elsewhere, Scottish taxpayers will continue to pay the 41% higher rate at income above £43,430, whilst counterparts in rUK will continue to pay the basic rate of 20% up to an income of £50,000 – assuming the UK Government leaves their higher rate threshold unchanged during their budget in March.

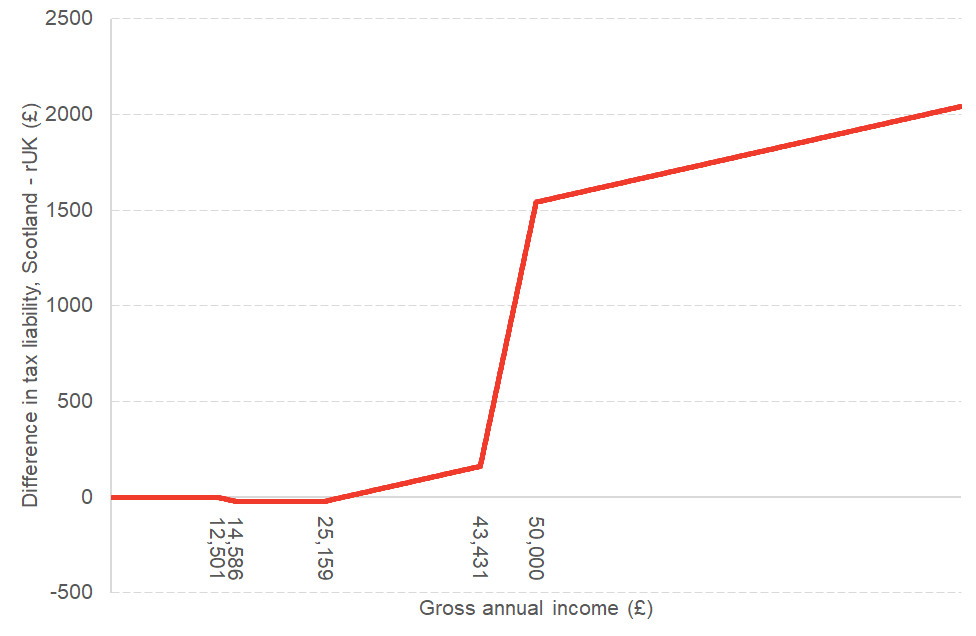

Chart: Difference in tax liability between Scotland and rUK in 20/21

In terms of the difference in liability between Scotland and rUK, Scottish taxpayers with income below £27,243 will pay less tax in Scotland than they would do elsewhere in the UK, to a maximum of £20.85 per year (or 40p per week).

So whilst it might be true that “that will ensure that 56% of Scottish taxpayers pay less than they would if they lived elsewhere in the UK. Scotland will continue to be the lowest-taxed part of the UK for the majority of income taxpayers”, it’s hardly the biggest tax bonanza ever.

Scottish taxpayers with income above £27,243 will however, pay more tax than their counterparts in rUK.

The difference is around £130 per year at income of £40,000, rising to £1,500 per year at incomes of £50,000. Should the UK Government increase the higher rate threshold – even just by inflation in March – this gap will widen.

As we highlighted above, taken all together, these measures are estimated to raise an additional £500+ million but the net revenue uplift is once again projected to be near zero in 2020/21 with the higher tax liabilities offset by weak growth in the tax base.

In terms of other announcements on tax, there was a tweak to the Non-Domestic Rates “Large Business Supplement”, costing £7-8 million a year (effectively a small tax cut for businesses occupying higher value premises). Offsetting this was a change to non-domestic property leases, raising around £10-11 million a year.

Spending Commitments

Continuing the theme of recent budgets, health has seen a disproportionate increase in spending, with the resource budget for health up just under 5% in real terms.

The core local government settlement (General Revenue Grant plus NDR revenue) is flat in real terms, although the government will point to a more generous 2% uplift once specific grants (largely associated with the early years and childcare commitment) are included. But this comes with major spending commitments that have to be met.

On the face of it, the other big winner was low carbon capital investment which is up around £500m, including schemes to decarbonise heat, transport and agriculture. Of course, whilst a substantial budget uplift, with such tough climate change targets to be met within the next decade, this is just the start of what is likely to be needed in the next few years.

Wellbeing

Much had been made on the government’s commitment that this would be a ‘wellbeing budget’.

But apart from lots of references to ‘wellbeing’ in the document, and a simple list of NPF outcomes in each portfolio, the budget was silent on how this supposedly new approach actually had any impact on the decisions taken today (or what has been stopped as a result of earlier budgets apparently not promoting ‘wellbeing’).

The SFC’s forecasts

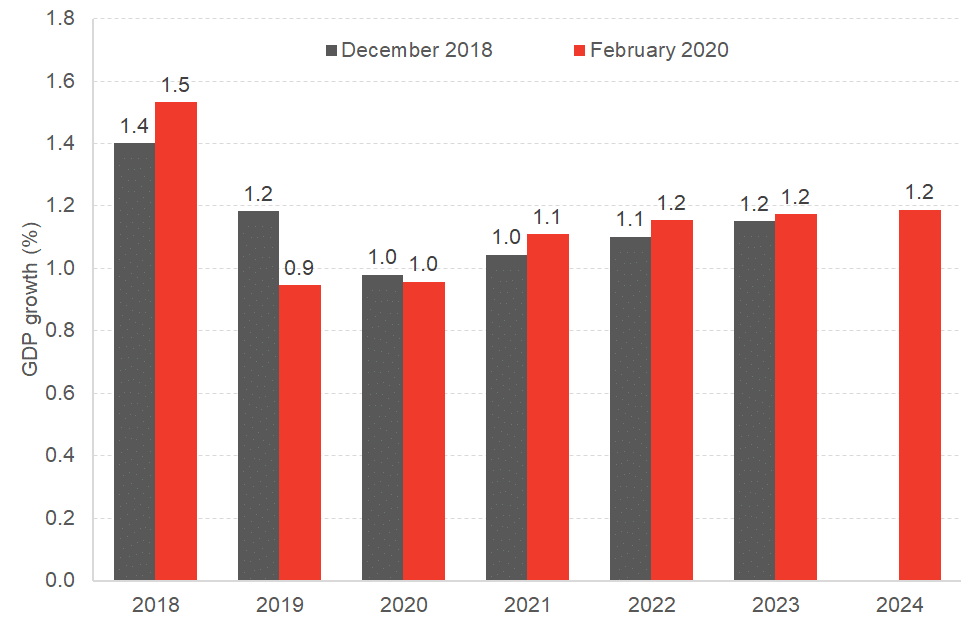

The Budget was accompanied – once again – by a relatively downbeat outlook for the Scottish economy by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC).

It has repeatedly warned of the prospects for slow growth in Scotland. Not a welcome message for some, but one upon which – at least to date – it has been proved broadly correct.

Average economic growth in Scotland in the decade leading up to the financial crisis was around 2% a year. Since 2010, average growth has been tracking at around half that.

Boosting productivity has been a challenge not just for Scotland but for many advanced economies. With the SFC seeing no real improvement in Scotland’s productivity performance over the next few years, economic growth is projected to remain below trend until at least 2024.

Chart: Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts of Scottish GDP growth

On the plus side, the outlook for employment remains positive helping to uplift growth in wages.

As the next Scottish election looms, the Scottish Government will be hoping that the SFC’s downbeat assessment will turn out to be wrong.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.