Earlier this week, Scottish Conservatives leadership candidate Jackson Carlaw committed to close the income tax gap between Scotland and rUK for those earning between £27,000 and £45,000.

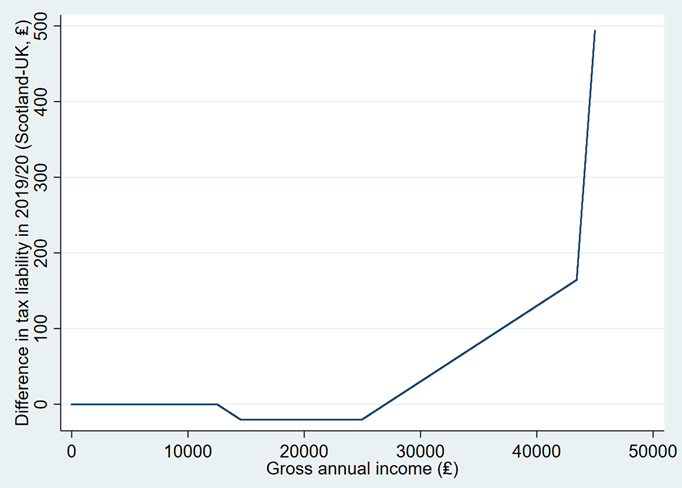

The majority of individuals with income in this range (those with incomes less than £43,430) currently face annual income tax liabilities of up to £150 higher than equivalent counterparts in rUK. But this difference increases rapidly beyond £43,430, reaching £500 at incomes of £45,000 (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Difference in income tax liability, Scotland minus rUK

How might Jackson Carlaw’s commitment be implemented in practice?

The obvious way would be to cancel the Intermediate Rate of tax in Scotland (which levies a 21% marginal rate of tax on Scottish taxpayers with income between £25,000 and £43,430 as opposed to the 20% rate prevailing in rUK) and to increase the Higher Rate threshold from £43,430 to £45,000.

(We are not aware of any detailed proposal in relation to income tax rates and bands. But this would seem the most logical way of implementing Jackson Carlaw’s objectives as set out in his speech. It is therefore the policy we model here.)

If this policy was implemented in 2020/21 it would reduce the government’s income tax revenues by around £270 million (Mr. Carlaw will not be in a position to implement the policy until 2022/23 at the earliest, but we examine the implications in 2020/21 for illustration).

This is a ‘static’ costing. It could be argued that a tax cut might induce some increase in labour supply which may mean that the policy ultimately costs somewhat less than this. However, the scale of the tax changes being proposed would suggest that the behavioural impact would be relatively small, so that the ultimate policy cost would only fall by £20 million or so from the £270 million static cost.

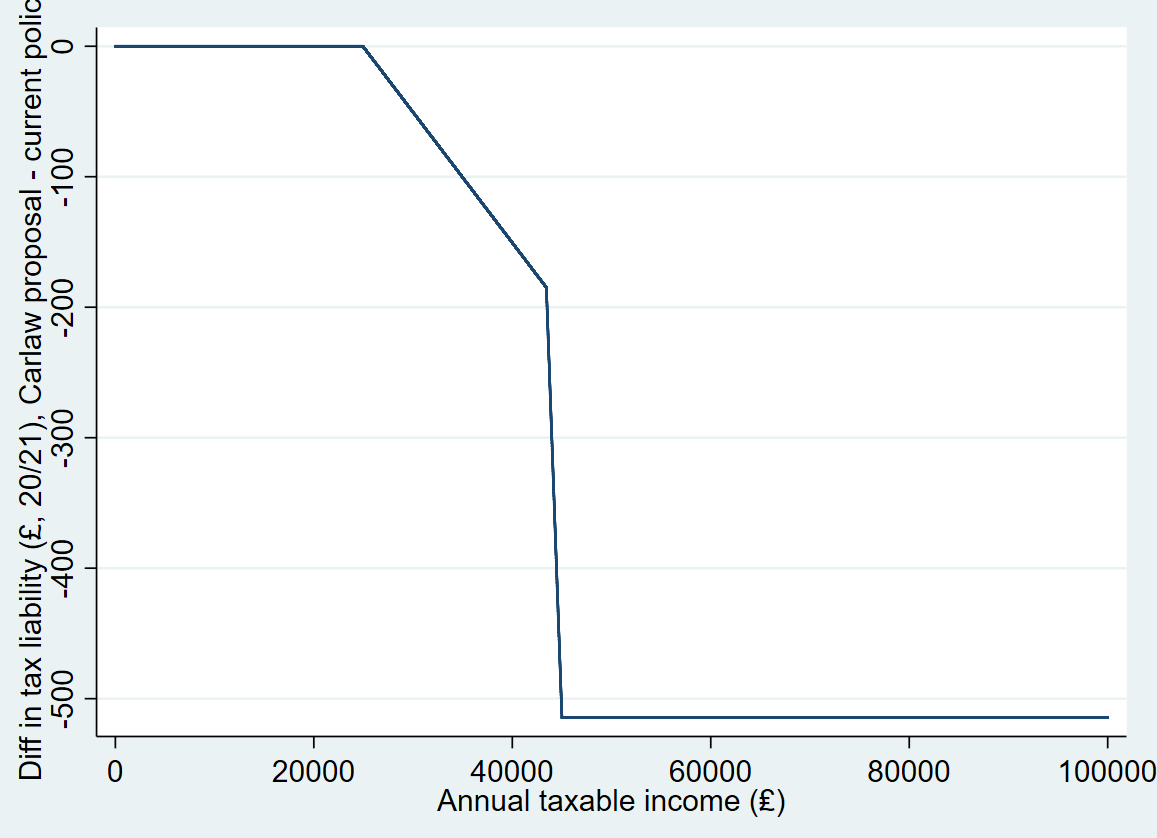

One of the reasons why the policy appears perhaps surprisingly expensive is that the elimination of the intermediate rate and increase in higher rate threshold would also apply to taxpayers with incomes above £45,000 (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Difference in tax liability between existing policy and Carlaw policy

What then would be the distributional implications of the policy across households?

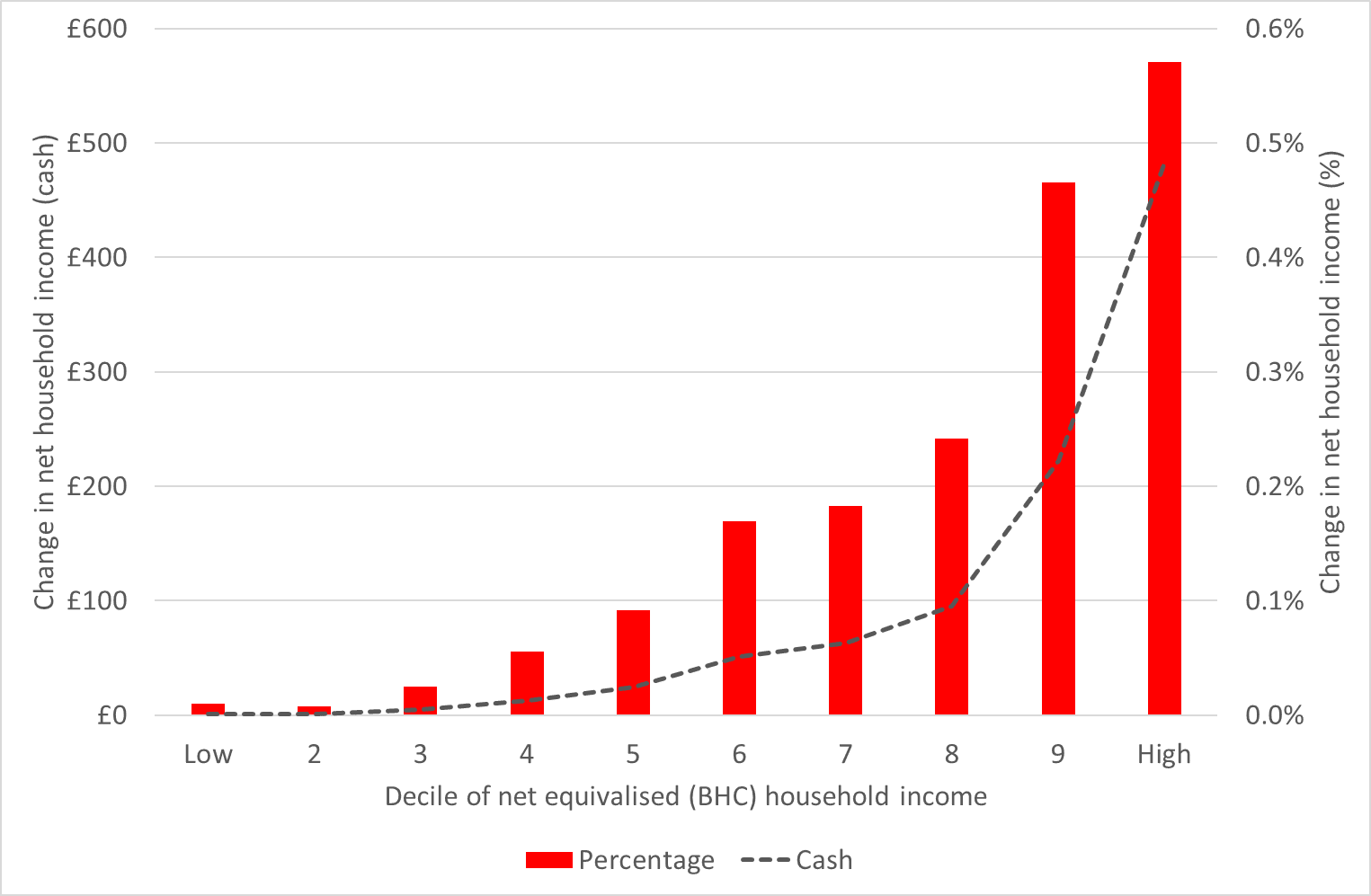

Chart 3 shows how the policy would affect average household incomes at each decile of the distribution. The policy predominantly benefits households in the upper two deciles (i.e. upper fifth) of the distribution.

Chart 3: Distributional impact of Carlaw policy

This result might be seen as puzzling, given the stated aim of the policy to help ‘middle earners’.

- Households in the bottom third of the income distribution contain very few individuals who have taxable incomes above £25,000.

- Those earning below £30,000 gain very little from the policy, as the difference in liability that they face relative to rUK is small.

- The percentage income gains are highest for those with taxable incomes between £43,430 and £45,000 (these individuals are at around the 85th percentile of taxpayers, i.e. they are in the top 15% of taxpayers ranked by income), and these individuals tend to live in households in the top fifth of the income distribution.

- Meanwhile the cash gain for someone with income of £100,000 is the same as someone with income of £45,000.

Hence a policy framed as supporting ‘middle earners’ predominantly benefits households at the top of the distribution of household income.

Recognising this, Jackson Carlaw has also indicated that any tax cuts for higher earners would be ‘delayed’. Whilst it is not entirely clear what this means, it suggests that additional measures would need to be taken to offset any gains to those earning above £45,000 from reducing the tax burden on those earning below £45,000.

Of course if the objective is to help ‘middle earners’ but not necessarily those earning above £45,000, then the cut to the intermediate rate could be offset by a further increase in the higher rate, to say 42p. At the moment, it is not clear whether this is what Jackson Carlaw intends.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.