Earlier today, Rachel Reeves announced in the House of Commons the outcome of the Spending Review for both resource and capital budgets across departments and devolved administrations.

It was a speech long on detail about many capital projects, but much of the lead was buried. In our preview last week, we noted that the envelope set out in the Spring Statement promised to be a reversal of Robert Chote’s 2015 quip about a ‘rollercoaster ride’: largesse in the short-run, followed by pretty steep subsequent cuts in real (and in some cases cash) terms in future years.

Capital spending brought forward, with defence the big winner

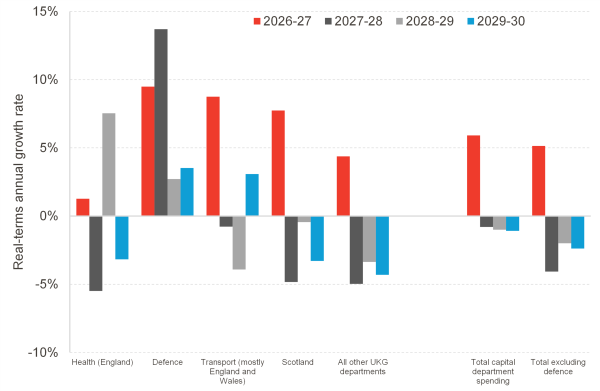

Not only has that proved to be the case on day-to-day spending (more on that below), but capital budgets have got in on the act.

If we exclude financial transactions – which are lending to the private sector rather than capital investment by the government – the profile of capital spending has been brought forward even further. We are now looking at a one-off boost to investment budgets of 6% in real-terms next year, followed by falls in each year.

Chart 1: Annual real-terms growth in capital budgets excluding financial transactions

Source: HM Treasury

In fact, the figures only get starker once we take into account that so much of the boost to investment is on defence. Non-defence capital spending falls by -0.9% a year in real terms going forward, meaning it’s nearly 4% lower by 2029-30 than this year.

This pattern is broadly reflected in the Barnett consequentials for Scotland. The Scottish capital block grant increases by £0.6 billion (7.7% in real terms) next year, but then fall back to below 2025-26 levels by the end of the decade.

One big risk to this plan is whether the capacity will be available to deliver all these capital projects at once. Major projects already have a habit of seeing larger cost increases than foreseen, and bringing so much capital spending forward could cause prices of inputs and labour increase to eat up the additional budgets – something to keep an eye out for in the coming months.

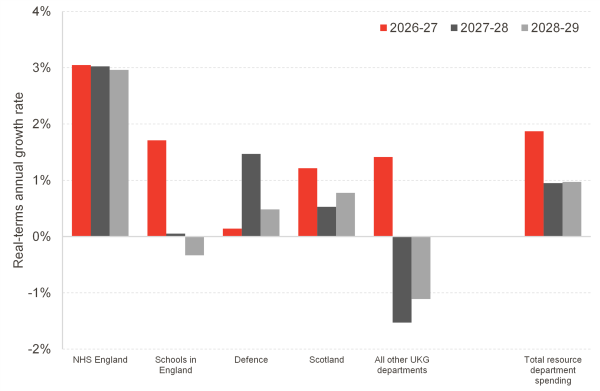

The pattern is similar on day-to-day spending, though less dramatic

Here too the pattern is for bigger spending increases in the short-run. The big exception is the NHS in England, which sees a nearly flat 3% boost in real terms, and which generates significant Barnett consequentials. Budgets other than health, schools and defence see a relatively healthy 1.4% increase next year, but this is followed by 1.5% and 1.1% falls in each subsequent year, meaning that their budgets are 1.2% lower in real terms by 2028-29 than this year.

The UK Government will no doubt argue that its efficiency drive will make it possible to do this while not cutting services, but we’ll reserve judgement on that. Similar initiatives in the past have had disappointing results; this one may well succeed, but it will have to buck the trend of history to do so, which would be no mean feat.

Chart 2: Annual real-terms growth in resource budgets

Source: HM Treasury, FAI analysis

What does this mean for the Scottish Government?

On the day-to-day spending side, funding grows at an average of 0.8% a year after accounting for inflation. This is slightly below the average for overall resource spending, so a bit less than we thought it might in our preview blog – largely because schools in England have done less well than we expected.

This allocation is also slightly lower than what the Scottish Fiscal Commission included in their outlook just a couple of weeks ago. The capital allocation is also less generous than the SFC had predicted, although there is an increase the financial transactions allocation.

Table 1: Comparison between block grants and SR 2025 and

| Block grant (£bn) | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 |

| Resource | |||||

| SR 2025 allocation | 41.5 | 42.7 | 43.8 | 45.0 | |

| SFC forecast (May 2025) | 41.6 | 42.9 | 44.3 | 45.6 | |

| Difference | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.5 | -0.6 | |

| Capital | |||||

| SR 2025 allocation | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.7 |

| SFC forecast (May 2025) | 6.3 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.1 |

| Difference | 0.0 | 0.3 | -0.3 | -0.2 | -0.4 |

| FTs | |||||

| SR 2025 allocation | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| SFC forecast (May 2025) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Difference | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

Source: HM Treasury, Scottish Fiscal Commission, FAI analysis

We have seen some Labour MPs and MSPs describing this event as increasing the block grant by £9.1 billion over the Spending Review period. While it is true that Barnett consequentials add up to this figure (across different periods for resource and capital), this doesn’t seem like a particularly transparent or helpful way of describing the changes. It essentially assumes that no additional funding would have been made available for the Scottish Government in cash terms relative to that in 2025-26 – which is not a credible baseline.

A much more insightful – though perhaps less cheery – conclusion from looking at the SFC’s forecast is that by 2028-29, funding will be £0.7 billion lower than their central estimate published on 29 May.

What about other spending in Scotland?

There were some additional announcements that will affect Scotland, though not through the funding of the Scottish Government. Clearly defence manufacturing – a significant part of which will happen in Scotland – will benefit, as will the investments in science in Edinburgh and in carbon capture and storage in Aberdeenshire. There was also an additional growth deal for Falkirk and Grangemouth.

GB Energy funding was also included in this Spending Review, although it seems that much of it will be in the form of financial transactions – although we’ll await confirmation of this. Nonetheless, if it serves to create additional investment by the private sector, it will benefit the areas where those investments take place.

How important will this Spending Review turn out to be?

As we discussed last week, spending reviews tend to be big processes across departments, but not necessarily of setting the stance of fiscal policy. As a reminder, today’s announcement nearly fully stuck to the totals set out in March.

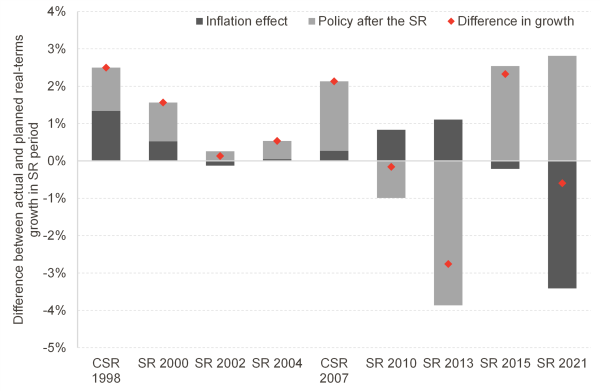

But the track record of spending reviews constraining public spending is much less clear, as chart 3 shows. Successive UK governments have topped up budgets between SRs, so that the totals and allocations laid out today may bear less resemblance to what will happen than you might think.

Chart 3: Breakdown of difference between planned and actual real-terms increases in spending during SR periods

Source: HM Treasury, OBR, FAI calculations

Of course, there is a lot more detail now that before the SR was conducted. It’s as if we’ve upgraded from a compass (totals and spending assumption prior to the SR) to a sat-nav. But just because we have a more detailed route doesn’t necessarily mean we know the actual route we will take – especially if unexpected obstacles arise in the future.

Nonetheless, the Scottish Government now has a baseline to work from. Clearly it’s not that different a baseline from what the SFC produced a few weeks ago (especially in the next couple of years), so one might wonder if the Medium-Term Financial Strategy could have been produced then after all. Nonetheless, we look forward to seeing how this SR is reflected in the MTFS and the new Fiscal Sustainability Delivery Plan in two weeks’ time.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.