Inevitably, the defining feature of all the manifestos this election is the spectre of constitutional change.

For the UK-wide parties this is an issue of Brexit (or stopping Brexit), whilst in Scotland there is the added question of independence.

Beyond these major constitutional debates, reading UK election manifestos can feel a strange business from a Scottish perspective. Most of the policy pledges relate to areas that are devolved, with the next Holyrood election not for another 18 months.

Nonetheless, these pledges will still have major implications for Scotland’s budget, whilst also framing the view of what policies might be politically viable here. This is true for spending commitments, but it is now increasingly true of tax policy too.

The choices facing the electorate are stark, not just on the constitution but also day-to-day tax and spending choices. It is no surprise that with so much uncertainty, Derek Mackay has shelved plans for a pre-Christmas Scottish Budget

So what do the manifestos imply for Scotland and the Scottish Budget?

The resource block grant

Many of the manifesto announcements proposed by the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats are devolved. This includes commitments on health, social care, education – including tuition fees – childcare and policing.

But the more Westminster spends on ‘comparable’ services in England, the larger the amount of money that will flow to Scotland’s block grant via the Barnett Formula.

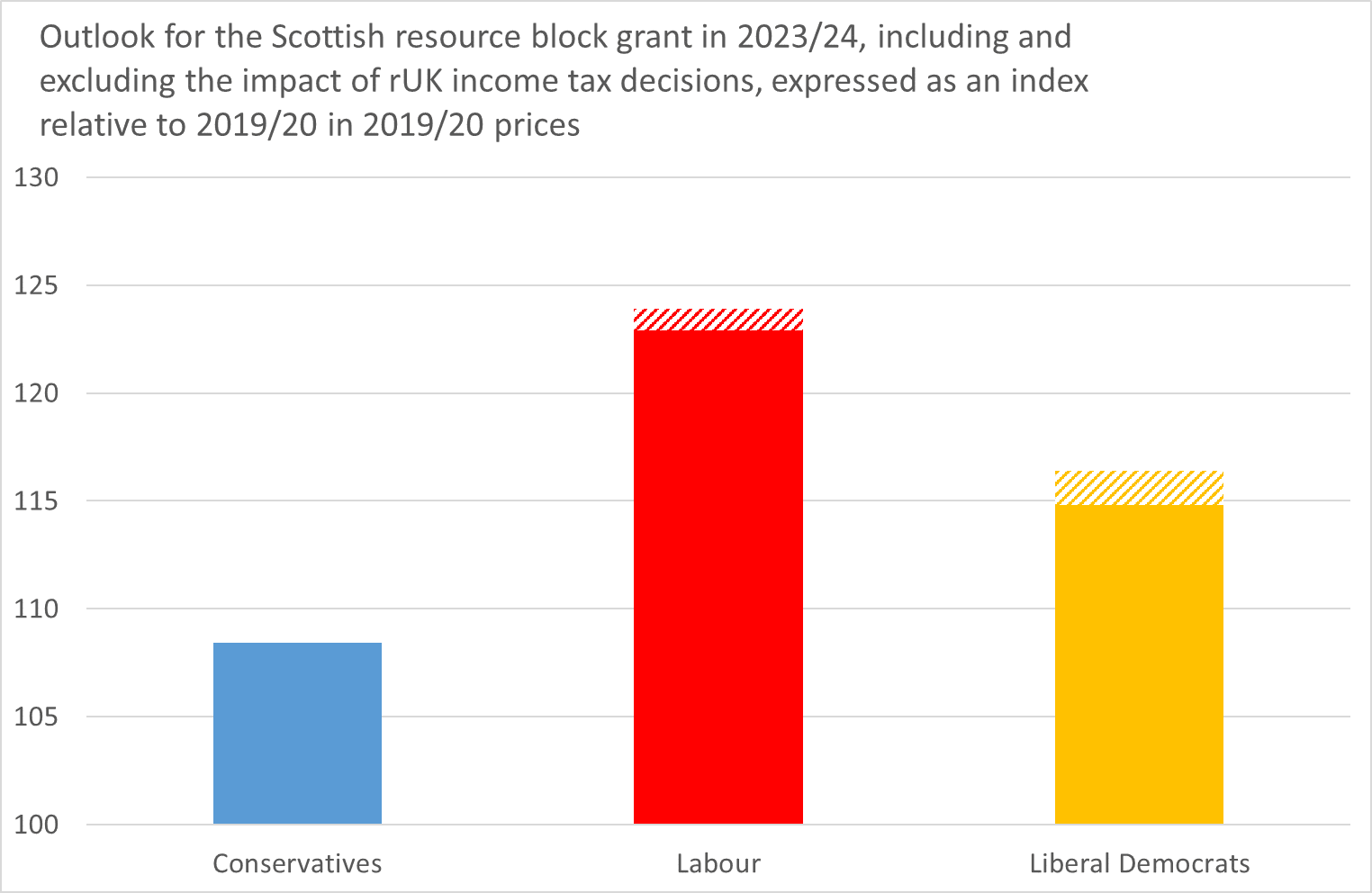

Chart 1 shows the implications of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrats manifesto pledges for the Scottish resource block grant (that is, monies to fund day-to-day public services as opposed to infrastructure investment).

Under the Conservative’s plans, the resource block grant will increase by around 2% per annum in real terms to 2023/24 – around £600m per year. Whilst this is relatively modest growth compared to the other parties, this will still represent the first sustained period of growth in Scotland’s block grant in nearly a decade. Indeed, this will take spending in Scotland back above 2010/11 levels for the first time since the ‘austerity’ period commenced.

Labour’s plans imply a much more radical increase in spending – growth in the block grant of around 5.5% per annum in real terms. This would be equivalent to an increase of around £1.7bn per year. These ‘consequentials’ stem from plans that include a substantial investment in pre-school and school education, the abolition of higher education tuition fees, increases in health and social care spending (including free personal care for over 65s) and a funding boost for local government.

How will this be paid for? Alongside a rise in borrowing, labour’s intention is to pay for this through tax increases on business and higher earners. These proposals include changes to income tax that would not apply in Scotland, but that would have further implications for the block grant – discussed further below.

The Liberal Democrat’s plans imply a block grant approximately half-way between the Conservative and Labour proposals. Their proposals include substantial increases in spending on childcare, schools, and health, to be funded by mixture of tax increases and a so-called ‘remain bonus’ (although it is hard not to be sceptical about how robust a figure this could ever hope to be).

But the block grant itself is only part of the story.

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats propose funding a proportion of their spending pledges by increasing rates of income tax.

These changes would not apply in Scotland because income tax is devolved.

As a result, the Scottish block grant is adjusted downwards to ensure that Scots do not benefit from UK spending increases that have been funded by higher taxes levied outside of Scotland. These downwards adjustments are likely to be around £500 million in the case of the Lib Dem proposal to put 1p on each band of income tax; and around £250 million in the case of Labour’s proposals to put up taxes on higher earners.

The ‘net boost’ to Scotland’s budget – whilst still substantial – will be slightly less than it would first seem (see shaded areas in chart 1).

Chart 1: impact of manifesto commitments on the Scottish resource block grant (Source: Fraser of Allander calculations). Notes: hashed areas denote part of block grant that would be deducted to account for income tax changes in rUK

The outlook for tax

On taxation, the difference between the UK political parties is also stark.

The Conservatives have promised no major changes in taxation, apart from a change to the threshold at which people will start to pay National Insurance Contributions that will see most people in work receive a small tax cut.

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats plan to raise taxes. Where taxes are reserved, such changes will apply in Scotland.

Corporation tax – which had been on a downtrend trend in recent years – would rise under both Labour and the Liberal Democrats to 26% and 20% respectively. The Conservatives have shelved pre-election plans to cut it from its current 19%.

As usual, all parties are promising efforts to cut down on tax avoidance, with Labour going even further with plans to introduce measures including a financial transaction tax.

As highlighted above, both the Liberal Democrats and Labour plan to increase income tax. Compared to the rates now set in Scotland, how would they compare?

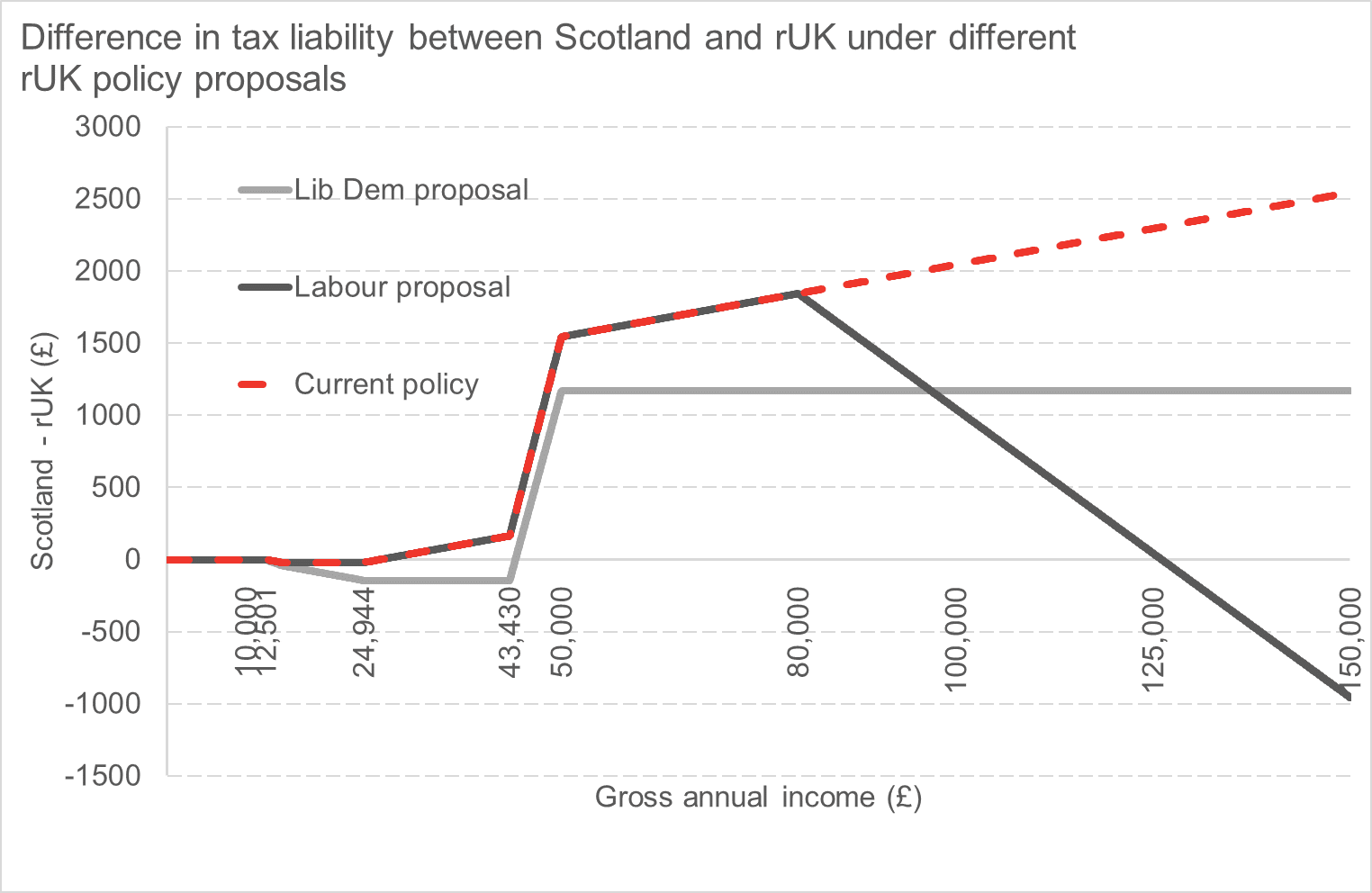

Chart 2 below shows the difference in income tax liability in Scotland compared to rUK under the current system, as well as compared to if the Labour or Lib Dem proposals were introduced.

Under Labour’s proposals, assuming that the Scottish devolved system remained the same, Scottish taxpayers earning between £25,000 and £125,000 would still pay more in income tax than those in rUK, whilst those earning above £125,000 would actually pay less.

The Liberal Democrat policy for rUK income tax would mean that Scottish taxpayers earning less than £43,000 (accounting for four fifths of Scottish income taxpayers) would actually pay less in income tax than their colleagues elsewhere in the UK. Those earning above would still pay more.

Chart: Difference in tax liability between Scotland and rUK under different party policies (Source: Fraser of Allander calculations)

Of course, we don’t know how Scottish Ministers may choose to respond should income tax policy shift significantly in the UK. Will they keep the current system in place in Scotland? Or will they be motivated to respond, perhaps to retain a narrative that Scotland has the most ‘progressive’ tax system in the UK?

Whilst income tax is the biggest tax, some of the manifestos propose a number of other tax changes that – whilst not applying in Scotland – may still influence Scottish policy.

The Liberal Democrats for example, propose changes to Air Passenger Duty that will increase the liabilities faced by frequent international fliers. APD in Scotland will soon be devolved to the Scottish Government, and after plans to cut it were shelved earlier on this year we await to see what action the government might take on APD in the future – particularly in relation to the ‘net zero’ ambition.

Similarly, on local taxation, the Liberal Democrats propose to replace Business Rates in England with a tax on land value of commercial sites. Labour meanwhile propose to double council tax on second homes that are used as holiday homes.

Social security spending

A number of social security payments – mainly associated with ill-health and disability, and focussed mainly on older age groups – are being devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

None of the main parties are proposing any major changes to the funding of these benefits or the way that they are implemented at UK level (changes to the funding associated with these benefits at UK level would affect the scale of resources transferred to Holyrood to fund the benefits in Scotland).

More generally the manifestos propose relatively modest change (or none in the case of the Conservatives) on working age social security spending. Labour propose to abandon Universal Credit, although do not say with what, and propose only a partial undoing of cuts implemented since 2010. The LibDems propose to abolish the ‘bedroom tax’ (which would free up around £40m of the Scottish Government budget that is currently spent on mitigating this in Scotland).

Whilst most social security spending remains reserved to Westminster, there appears relatively little in the manifestos that will help the Scottish Parliament to achieve its target to more than halve the child poverty rate by 2030.

The capital block grant

The discussion so far as focussed on day-to-day public spending, but what about investment?

The three major parties have each committed to substantial increases in capital (i.e. infrastructure) spending. These increases will impact the level of capital investment that the Scottish Government has at its disposal, via the Barnett formula.

The Conservatives have said they will allow net investment to rise to 3% of GDP (from just over 2% currently). This would result in an additional £1.7bn (one third) in real terms flowing to the Scottish Government to fund capital investment in Scotland by 2023/24.

The Liberal Democrats have pledged a £130bn UK-wide package of ‘additional investment’ over the next five years. It is difficult to say exactly what this might mean for the Scottish budget, as it is not clear what the package is additional to, but it seems likely to equate to a level of uplift somewhat higher than implied by the Conservative plans.

Labour has proposed a colossal increase in capital spending, trumping the plans of all other parties in sheer scale. But as the IFS and others have pointed out, there are serious questions about how easy it will be to deliver such levels of investment even over a five year period. It’s simple not possible to turn on the spending plans so quickly, with major infrastructure investments taking years to plan and deliver effectively.

What does all this mean for Scotland?

Last year the Scottish Government announced what appeared at the time to be an ambitious aspiration to increase capital investment in Scotland by £1.5bn by 2025. On the basis of the commitments of the Conservatives, Liberal Democrats and Labour, that aspiration now looks attainable simply through the projected flow of Barnett consequentials. On this basis, the justification for the SNPs demand for additional borrowing powers is less clear.

Wider economic policy issues

Alongside big policy differences on the constitution, public spending and tax, there are other significant differences in public policy more generally, not least in relation to the economy.

In comparison to Labour, the other parties’ plans on the economy look tame. The Conservatives manifesto contains no new economic policy of any significance. And some may highlight the somewhat odd scenario of their one major economic policy – to ‘get Brexit done’ – being one that will actually make us financially worse off.

In contrast, Labour plan to ‘re-write the rules of the economy’. This includes arguably the most radical proposed overhaul of the way companies are owned and run in decades, including nationalisations and changes to the way companies are supervised by government. Alongside this, they plan to put in place a swathe of new labour market regulations, give employees a direct stake in the profits of major companies, and see a substantial increase the minimum wage.

There are of course major questions about the possible economic implications and risks of such policies. But it is clear that a Labour Government would usher in a period of significant change in the UK (and Scottish) economy, including a fundamental re-think of the role of the state in our economy.

On climate change, all parties are promising action to deliver net zero. But for all the high-level ambition, there remains little detail and costings for how all parties plan to actually deliver it.

The SNP

Our focus here has been on the implications for Scotland of the manifesto pledges of the main pan-UK parties.

The SNP’s manifesto does not include detailed plans for overall public spending at the UK level, although it does argue for further increases in health spending in England which would in turn boost the Scottish budget.

Under the SNPs plans for overall public spending, the block grant will increase in real terms – by more than implied by the Conservatives, but not by as much as proposed by Labour or the Liberal Democrats.

The manifesto calls for some costly policies on social security, notably on those above state pension age. Like all the main UK parties it commits to retaining the ‘triple lock’, ensuring that the State Pension continues to grow faster than working age benefits. And like Labour, it commits to reversing plans to increase the state pension age beyond 66, and to provide some compensation to ‘WASPI’ women.

More broadly, the manifesto calls for the devolution of more powers, notably in relation to national insurance contributions and employment law.

There are clearly arguments for and against further devolution of such powers. For example, whilst there is a case for devolving national insurance contributions, given the integration with income tax, it could lead to the Scottish budget becoming even more reliant on one particular tax base.

One area of eminent sense is the call – once again – for a differential approach to migration in Scotland. With a demographic outlook that looks quite different to the UK as a whole, this is a no-brainer and it remains puzzling why UK parties continue to resist such an idea.

The ‘big’ manifesto commitments of the SNP are to block Brexit and to give the Scottish people the opportunity to vote in a second independence referendum. This too opens up a host of economic and fiscal questions – see here for a recent overview on such issues.

Concluding points

A cynic would be justified in arguing that manifesto spending plans should be taken with a fairly large pinch of salt.

As highlighted by the IFS, the current Conservative government’s spending plans for 2020/21 are £27bn – or 9% – higher than the plans they had set out in 2017. It could be argued that a Conservative Government would likely end up spending somewhat more than implied by its manifesto, whilst a Labour government may struggle to spend as much.

Some themes are common to each manifesto.

Resource spending is set to increase in real terms; the Scottish block grant will return to pre-austerity levels under the Conservatives plans, surpass it under LibDem plans, and massively overshoot it under Labour’s plans.

Capital investment is on course to increase substantially whoever wins the election.

But there is also some very clear water between the manifestos, both in terms of the size and role of the state, and in the degree of constitutional change. The Conservative manifesto envisages some spending increases in health and education, but otherwise a continuation of current trends.

Labour’s plans are for a very significant increase in tax and spending, as well as the renationalisation of a number of key utilities providers – in effect a major shift in the structure of the UK economy.

On constitutional change, the Conservatives aim for a relatively hard Brexit in January next year, the Liberal Democrats plan to stop Brexit entirely, and Labour are somewhere in-between. Stopping Brexit is also a key plank of the SNP manifesto, together with independence for Scotland – and in the meantime, additional powers over immigration, national insurance and employment law.

Most voters will be drawn to one party over another on the basis of these big ticket constitutional items.

But depending on which party forms the next government at Westminster, the implications for the Scottish economy and Holyrood’s tax and spending powers could not be more different.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.