Chancellor Phillip Hammond surprised many with a headline grabbing £2 billion of consequentials for the Scottish Budget. So where is the money coming from and what does it mean for the overall Scottish Budget?

Phillip Hammond was able to offset some pretty dire figures about the outlook for the economy with a series of new policy announcements – particularly targeted at supporting housing in England.

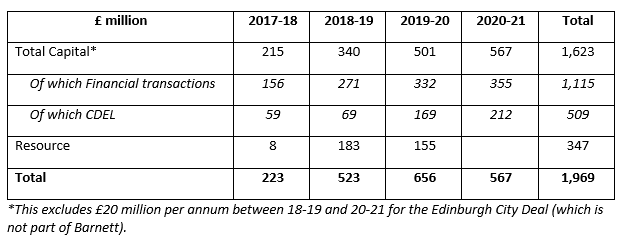

The table below summarises the consequentials for Scotland.

Over the period 2017-18 to 2020-21, the Scottish budget will be boosted by around £2bn in total.

Within this, £1.6 billion – or just over 80% – is in the form of capital spending with 20% on the resource side of spending. Resource spending is that which covers day-to-day spending on things like pay and service delivery.

Capital spending

Of the £1.6 billion capital uplift, the vast majority of this is in so-called financial transactions.

Financial transactions are becomingly increasingly common for a wide variety of activities, although they can’t be used to support day-to-day spending on public services. Instead they are initiatives that help support investment in the economy through the provision of government-backed loans and equity.

The UK Government announced a series of measures to support first-time buyers through the use of financial transactions. As housing is devolved to the Scottish Parliament, the Scottish budget receives additional consequentials.

In total, the increase in financial transactions to the Scottish Budget is worth around £1.1bn over the period from 17/18 to 2020/21.

Scottish Ministers are constrained in how these financial transactions can be used, but they are not restricted to providing loans only to homebuyers (e.g. they could provide loans to small businesses).

The budget also announced around an additional £500 million more traditional capital spending, i.e. investment in roads and public buildings (on top of which is added a further £60 million of support for the Edinburgh City Deal).

Resource spending

There was also an increase in consequentials for resource spending. These consequentials are more modest, with a cumulative increase of around £350 million over 2017-18 to 2019-20.

The rise of just £8 million for 2017-18 is particularly modest. The Chancellor announced additional spending on health in England of £350 million. This would normally translate into higher consequentials for Scotland than £8 million (i.e. closer to £30 million), but cuts elsewhere – particularly in the Department of Education’s Budget – have offset this increase.

Next year the increase is £180m – to put this in context the Scottish Government’s proposals for increasing income tax next year ranged between £80m-£250m.

Real-terms impact on the budget

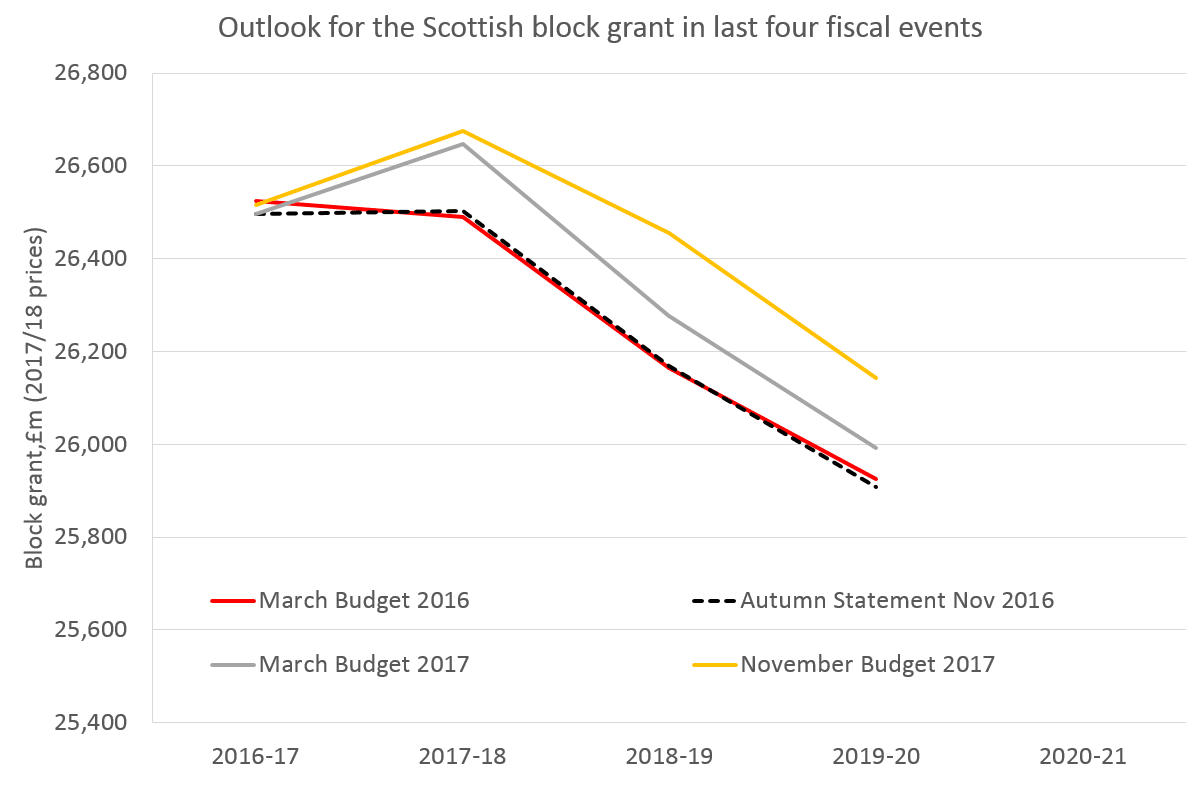

As the chart highlights, the resource block grant remains on track to fall in real terms over the next two years.

By 2019/20 the resource block grant will be around £500 million lower than in 17/18 (although only £375 million relative to 2016/17).

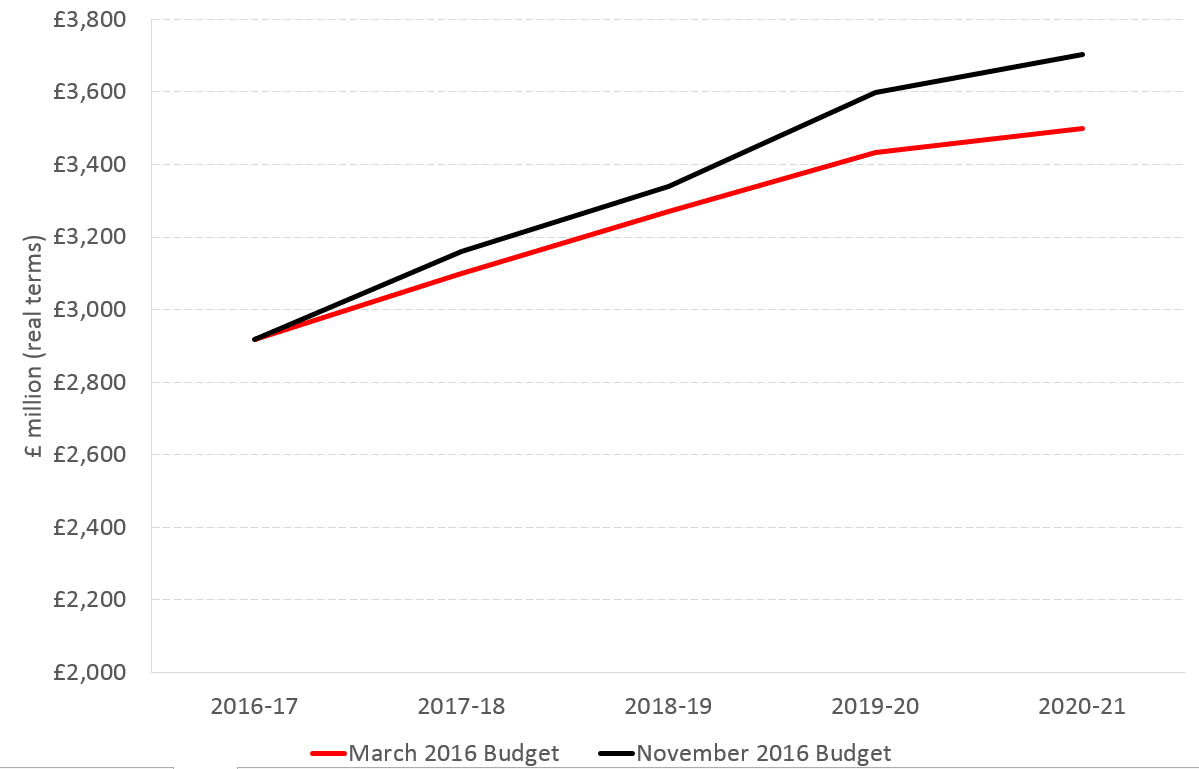

In contrast, the block grant for capital expenditure (even excluding financial transactions) is forecast to increase in real terms over the next two years, by 6% in 18/19 and 8% the following year.

What does this mean for next month’s Scottish Budget?

Firstly, it is important to remember that today’s budget is only half the story. To find out the exact profile of the Scottish budget over the next few years we require the tax forecasts from the Scottish Fiscal Commission (and how they will interact with how the resource block grant outlined above will be adjusted). What will be crucial will be the SFC’s assessment of the outlook for the Scottish economy, which is now even more interesting in the light of today’s much weaker outlook for the UK provided by the OBR.

Secondly, the significant cut in stamp duty for first time buyers in England will not apply in Scotland. Of course, the Scottish Government will face pressure to implement a similar cut to LBTT in Scotland, but a tax cut is likely of course to reduce the government’s revenues. Housing affordability is not quite so acute as in parts of England – notably London and the South East – but it is still an issue. The question for the Scottish Government is whether or not it thinks the best way to address housing affordability in Scotland is through offering more generous tax breaks.

Finally, with the consequentials from today’s Budget landing primarily on the capital side, the challenge remains for Derek Mackay as to how best to balance his resource budget with major commitments like additional support for the NHS, more money for childcare and public sector pay uplifts all to be paid for.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.