The Covid pandemic has had a huge impact on our working lives. It has seen many of us work from home, and a number of people placed on furlough from their employer as well as job losses. Tracking this in the available economic survey data has proven challenging, with little change in headline indicators like the unemployment rate. We’ve also lacked data at a regional level on key metrics like redundancies, and data on hours worked at a regional level is only beginning to emerge.

This week the Office for National Statistics (ONS) released the latest results from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE). These statistics are drawn from a 1% sample of PAYE records and are usually thought to be the most reliable statistics on hours and earnings for employees across the UK. But these too have been affected by challenges around Covid 19.

It is for this reason that the 2020 release comes with a health warning. Issues with collecting the data this year has meant that the achieved sample size is around 25% smaller than would usually be the case, which means that the results published this week are more provisional than usual.

Also, because the statistics do not include the self-employed, they do not give us the whole picture of what is occurring across the labour market. Nevertheless, these figures are usually an extremely useful gauge of what is happening with earnings across the economy. In this article we review the headline messages from these data.

How are ‘earnings’ calculated?

ASHE’s headline measure of earnings is based on median weekly pay for full-time employees. ‘Full-time’ refers to someone working over 30 hours a week (median full-time hours are 37.5 hours a week).

ASHE uses the median rather than the mean for its headline earnings statistics to avoid any skewing due to inclusion of a small number of people with very high pay in the sample. The median is arguably a better gauge of the ‘average’ conditions of the labour market.

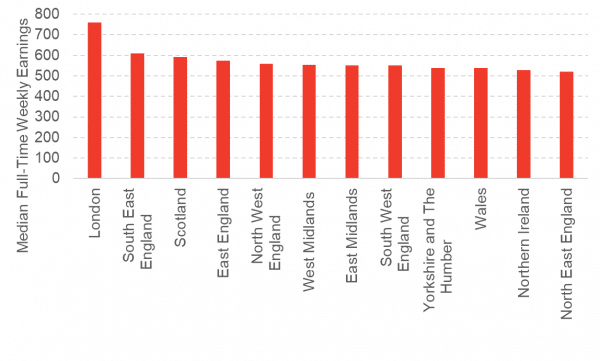

Median weekly pay for full-time employees for the UK was £586 in April 2020 (roughly £31,500 a year). These figures are gross pay, so before any deductions for tax or national insurance.

Median weekly pay varies across counties and regions.

Chart: Median Full-Time Weekly Earnings across the UK, April 2020 (£)

How have the figures changed since last year?

The data for ASHE 2020 is based on the pay period that includes the 22nd April 2020. The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme was launched on the 20th April and as of midnight, on the 23rd of April, 3.8 million jobs had been furloughed[i].

According to the notes accompanying the data release, furloughed employees will appear on payroll with their normal hours (this is the basis on which furlough pay was calculated). Any reduction in aggregate hours worked will therefore be from fewer people working (i.e. due to unemployment) rather than due to furlough.

However, we do see the impact of furlough on pay where people only received 80% of their pay (i.e. their employers did not top earnings up to 100%). All else being equal, this will bring down average earnings (people will be working the same hours but for lower pay).

However, this is possibly only half the story. If job losses that occurred at the start of the crisis were disproportionately lower paid jobs, then this could actually increase average earnings. There will be fewer lower paid jobs affecting the average.

Working out what has happened, with figures that are likely to be revised, is at best tricky, and at worst totally inadvisable!

At the UK level, the figures show that median full-time weekly earnings have fallen, in real terms, by 0.9%. In Scotland, however, the figures show growth of 1.8%.

If we wanted to try to explain the differences between Scotland and the UK average then there are a number of possible reasons we could look at.

Firstly, Scotland has a larger public sector than the average over the whole UK. At the UK level, as you would expect, the reduction in earnings has been concentrated in the private sector. Scotland therefore could have been relatively protected to some extent.

Secondly, it could be the case that employers in Scotland have been more likely to top up furlough payments to 100%. Indeed, there is some evidence provided in the ASHE release that indicates that a lower proportion of Scottish employees have been furloughed at reduced pay compared to the UK average. Again, there is uncertainty over the accuracy of these estimates.

Thirdly, there may have been more job losses in Scotland concentrated at the lower end of the earnings distribution, hence ‘average’ earnings have increased.

There are other possible explanations, but it might be wise to accept that this data is more volatile than usual and to resist trying to come to any firm conclusions on the reasons why.

Proceed with caution

Given that ASHE is, usually, the most reliable estimate of earnings in the UK, it will no doubt feature in analysis and commentary over the months ahead. Indeed the broad picture it paints of earnings changes at the UK level seems reasonable.

However, there are reasons why reading too much into year-on-year comparisons across regions and sectors should be avoided.

Apart from any concerns over reliability, this data is a snapshot as of the start of the crisis, and is unlikely to be reflective of where the labour market is today or where it goes in the following months.

Piecing together the reality of what Covid-19 has done to our economy will take more than just one data source, and data sources that we are used to relying on may need to be viewed with more caution than usual. As always, but even more important now, corroboration with different sources of data, both quantitative and qualitative, will give us the best understanding of what is going in the labour market.

[i] https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/hmrc-coronavirus-covid-19-statistics

Authors

Emma is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute