How have Scotland’s revenues from income tax been performing since income tax powers were transferred to the Scottish Parliament in April 2017?

This is clearly an important question to ask. The Scottish budget in any year is determined in part by the rate of growth of Scottish income tax revenues per capita since 2016/17 compared to the growth of equivalent income tax revenues per capita in the rest of the UK (rUK).

We are nearly at the end of the second year of Scottish income tax devolution. But official income tax revenue outturn figures for 2017/18 will not be published until this summer, whilst outturn figures for 2018/19 will not be available until summer 2020.

Whilst income tax revenue data is not yet available, HMRC has published some information on the number of taxpayers who pay tax through Pay as you Earn (PAYE), and the average income of those PAYE income taxpayers, in 2017/18 and the first two quarters of 2018/19.

The data can be used to glean an initial sense of how Scottish income tax revenues are likely to be performing relative to rUK, although it is limited in several ways. In particular, it covers only PAYE taxpayers who have earnings from employment, but excludes those who pay tax on occupational pensions through PAYE, and those who pay income tax through self-assessment. The data covers Scotland and the other UK regions and nations.

A concerning picture

So what do the data say? From a Scottish perspective, the picture is concerning.

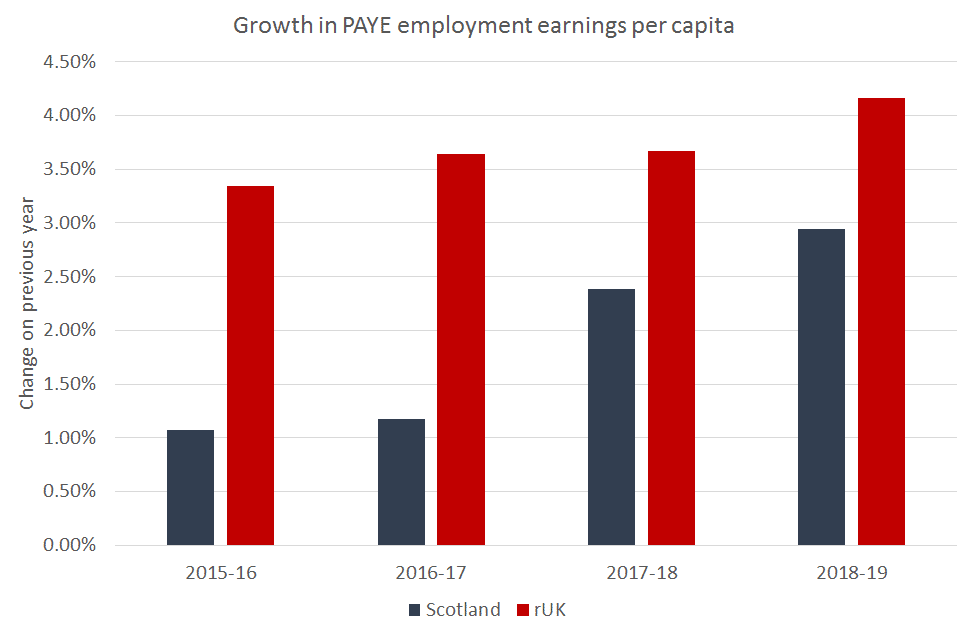

In 2017/18, total PAYE employment income per capita in Scotland increased by 2.4%, notably below the 3.7% increase in PAYE employment income per capita in rUK.

In the first two quarters of financial year 2018/19, PAYE employment income per capita increased by 2.0% and 3.9% in Scotland compared to the same quarters in the previous year. This was slower than the equivalent rUK growth rates of 3.6% and 4.7%.

The slower growth in total taxable income per capita in Scotland is not due to slower growth in the proportion of the population who show up in the PAYE statistics. It is purely down to slower growth in the average earnings of Scottish relative to rUK PAYE taxpayers. In 2017/18, average earnings of PAYE taxpayers grew 2.5% in Scotland against 3.3% in rUK. This trend of slower Scottish growth in average earnings continued in the first two quarters of 2018/19.

Two questions follow: why is Scottish earnings growth relatively weaker, and what does it mean for the Scottish budget?

Why is Scottish earnings growth so weak?

On the question of ‘why’, one thing we can say is that the trend is unlikely to reflect behavioural responses to the Scottish Government’s income tax policy. We can say this because lower growth in Scottish average earnings was observed in 2015/16 and 2016/17, before income tax powers were devolved. In fact if anything, Scotland’s relative performance was even weaker in that period (see chart).

Slower Scottish earnings growth thus reflects a much longer term challenge – perhaps linked to the decline in the offshore sector that started in 2015. Perhaps it also reflects a hangover from the heady days of 2014, when the Commonwealth Games and Ryder Cup boosted visitors and economic activity.

But flippant comments aside, the extent of Scotland’s under-performance according to this data should not be underestimated. Scotland was at the bottom of the UK’s regional league table for average pay from PAYE earnings in 2015/16, 2016/17 and 2018/19, and has remained so in the first two quarters of 2019/20. There is an urgent need to understand more about the drivers of this pattern.

What could this mean for the Scottish budget?

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that weaker Scottish earnings growth will be reflected in tax outturn data once it is published.

The exact scale of the likely revenue gap is difficult to anticipate with this data. Knowing that average Scottish PAYE incomes from employment are growing less quickly than average rUK incomes from PAYE employment tells us nothing about the relative growth of taxpayer incomes at different parts of the income distribution (i.e. in different tax bands) – but this distributional question matters for tax revenues. Moreover, the data tells us nothing about the relative performance of occupational pension income, or self-assessed income, which are both important contributors to total revenues.

Two important implications follow.

First, the conclusion that Scottish tax revenue growth will be weaker than it would have been if rUK performance was matched has already been reflected in the forecasts underpinning the 2019/20 Scottish budget. These forecasts show Scottish tax policy adding only £182m to the Scottish budget, despite the fact that Scottish taxpayers are paying more than £500m more in income tax revenues than they would be if the rUK tax policy applied (i.e. most of the £500m boost to the Scottish budget through the Scottish tax policy is offset by weaker underlying Scottish income growth).

Second, the HMRC data also suggest that the tax forecasts made in 2017/18 and in 2018/19 may have been too optimistic. If that assessment turns out to be true, the Scottish Government may face a ‘reconciliation’ in both its 2020/21 and 2021/22 budgets. The reconciliations reflect the difference between the forecasts made when budgets were passed, and the final outturn data. According to the SFC’s latest forecasts, these reconciliations could be £145m and £472m in the 2020/21 and 2021/22 budgets respectively. This money will have to be found. The Scottish Government could address this by borrowing, using resources built up in the Scotland Reserve, raising taxes or reducing spending in those years.

On a final note, the data reveal a problem inherent in tax devolution. Tax devolution is often proposed as a way to create a stronger link between economic performance and a devolved institution’s budget. This, the theory goes, will make politicians in those devolved institutions more financially accountable and responsible for the policies that they implement. But the argument supposes that economic performance is purely determined by the policy actions of devolved politicians. Clearly this might not always be the case. An oil and gas sector entering its twilight years and a population that is ageing more quickly than in the UK as a whole are just two examples where issues outside of the Scottish Government’s control may have an impact on devolved tax revenues.

Whatever the reason for this weaker performance, it doesn’t represent good news for the Scottish Budget. The indications are that the Scottish income tax base is growing more weakly in Scotland than in rUK, with implications for the resources available to fund public services.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.