Since February’s Budget, there has been discussion about income tax in Scotland and public spending.

Oddly, the debate was sparked by adverts – rather good ones we might add! – on the Tube promoting Scotland as a place to live.

Some – such as London MP Greg Hands – have responded by arguing that moving to Scotland would mean paying higher taxes.

This has been countered by others who argue that whilst (some) taxes may be higher, the quid-pro-quo for paying more tax is higher public spending and benefits such as free University tuition, more generous childcare, free personal care, free prescriptions etc.

So who is right?

Some context

Before going any further, we need to be clear what we mean by ‘tax’. We focus upon income tax as this sparked the discussion.

In this blog, we discuss two points:

- Do we actually pay more income tax in Scotland for a given level of income?

- What is the link between income tax and levels of public spending in devolved areas?

Do we actually pay more income tax in Scotland for a given level of income?

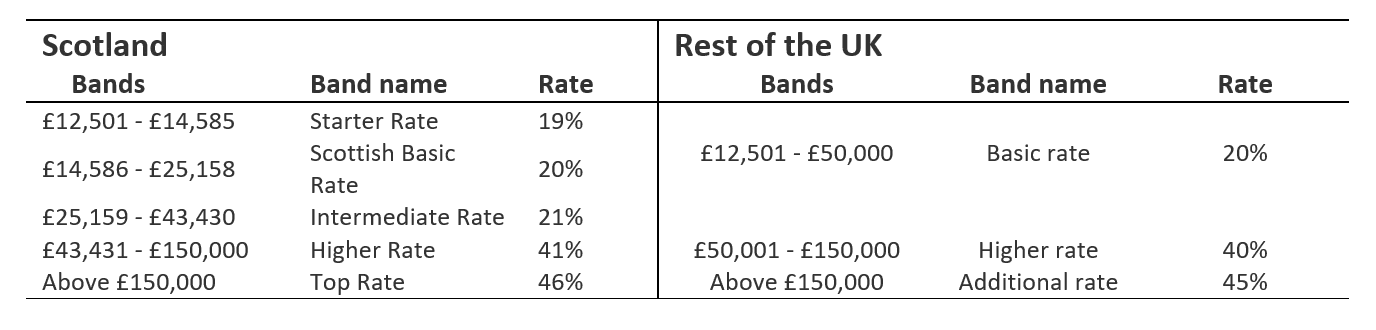

The table shows tax bands and rates in Scotland compared to rUK.

So, do people in Scotland pay more tax?

The answer is it depends. Do you look at it from the perspective of the number of people paying more tax? Or from the perspective of how much is raised across the tax paying public?

If your income is below £27,200 in Scotland you will pay less income tax than if you lived in rUK. If you earn above £27,200 you will pay more.

Given the distribution of income, this means that the majority of income taxpayers (56%) pay less income tax in Scotland – albeit the maximum anyone in Scotland’s tax bill is lower than someone with the same income in rUK is around £20 a year (or a mammoth 40p per week!).

On the flip side, Scottish taxpayers with incomes above £27,200 pay more tax than they would elsewhere in the UK. The difference is around £125 for someone earning £40,000, £1,540 for someone on £50,000, and £1,840 for someone earning £80,000.

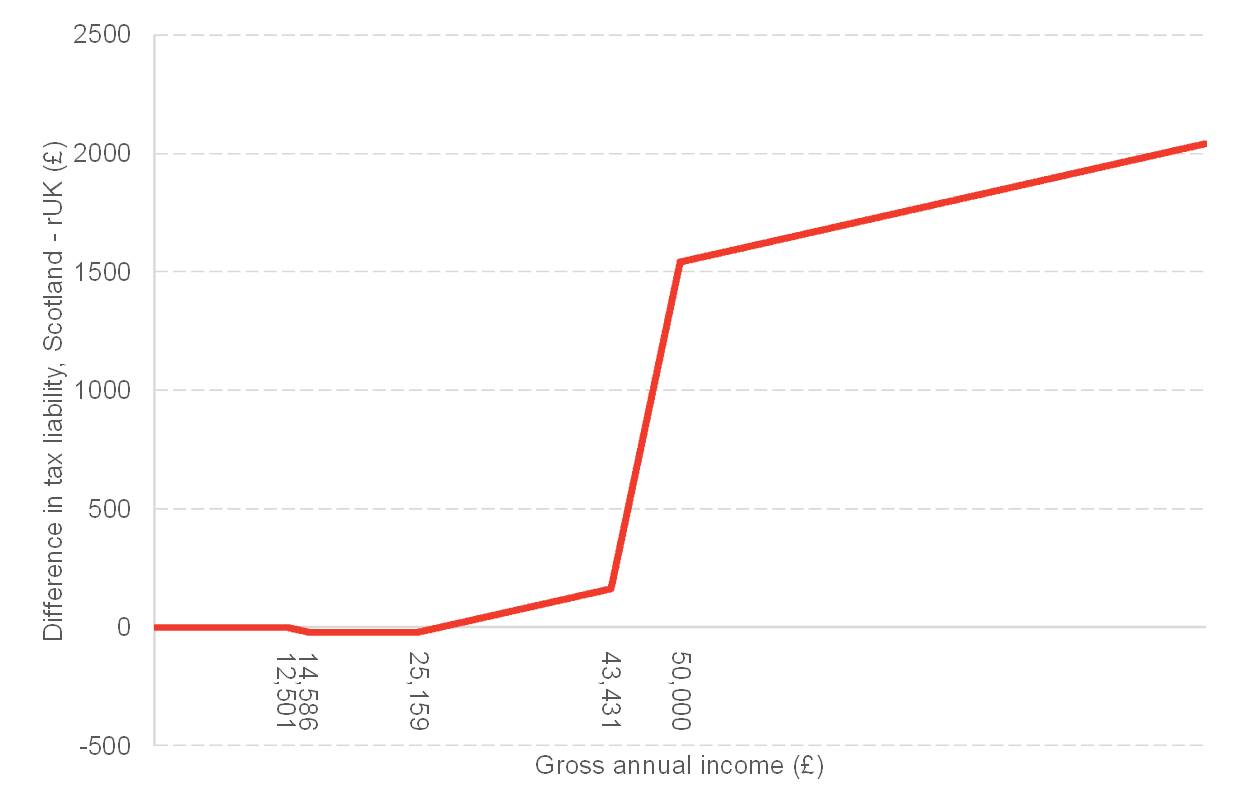

Chart 1: Difference in tax liability, Scotland minus rest of UK.

These tax burdens on higher earners means that the tax regime in Scotland does actually raise more in income tax than if the UK system had been implemented – the Scottish Government estimates this to be to the tune of £456m in 2020/21 (or £591m prior to any behavioural response).

In summary, whilst the majority of tax payers might pay very marginally less tax than in rUK, the overall tax burden in Scotland is indeed higher.

Is devolved public spending higher in Scotland than in rUK?

To answer the next part of the question we need to look at total devolved spending.

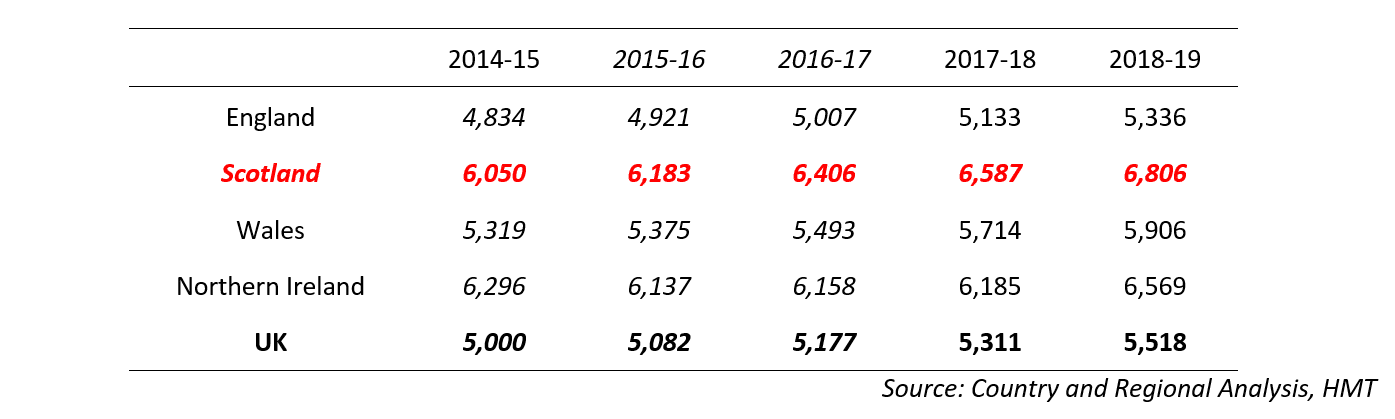

The table below shows spending per head across the UK on day-to-day public services like health and education (but excl. social protection, defence and other ‘non-identifiable’ spending like debt interest and UK-wide assets and institutions).

It’s not a perfect measure of ‘devolved’ spending, but as close as can be achieved with the data.

Spending per head on mostly devolved services

So yes, devolved public spending is around £1,300 per capita higher in Scotland than equivalent spending in the UK as a whole.

This spending differential isn’t new and pre-dated tax devolution and recent decisions by the Scottish Government to increase tax (more of this below).

Do higher levels of income tax fund higher public services spending in Scotland?

We have established that the tax regime in Scotland is designed to raise more revenue, but that the majority of individuals pay fractionally less than if they lived in rUK.

Is it accurate therefore to say that Scotland gains from higher spending as a result of this policy?

The answer to this also depends on how you look at! In other words, what is the counterfactual?

The Scottish Government’s tax policy is projected to raise an additional £456m beyond what it would have had it not chosen to make these changes to income tax bands and rates. So on this basis, yes, the tax policy does support higher spending in Scotland. This is equivalent to tax raising of £80 per person compared to the UK policy.

But another counterfactual is also possible. Is the Scottish budget £456m better off than it would have been if income tax had not been devolved at all?

The answer to this is no.

The latest figures show that although the government is raising around £456 million more in tax, the net benefit to the Scottish Budget is just over £40m.

So rather than £80 per head, the net gain is less than £8 per head.

What explains this? Following tax devolution, the Scottish budget no longer receives a share of increases in UK-wide income tax revenues. Instead, it benefits from growth in Scottish income tax revenues only. The problem is that, in the past three years, growth has been more buoyant in rUK than it has been in Scotland. So whilst the Scottish Government has increased Scottish tax rates, the tax base has grown relatively more weakly than the rUK tax base.

So, this can be summarised by saying:

- The Scottish Government’s tax policy will increase spending this year by around £456m, compared to had UK policy been followed;

- But, the Scottish budget in 2020/21 will only be around £40m (£8 per head) better off, compared to if income tax devolution had not happened, because of weaker growth in Scottish incomes.

But if the Scottish income tax policy is contributing only around £8 per capita to the spending differential of more than £1,400, what accounts for the remainder?

The answer is that the block grant provides Scotland with a relatively more generous settlement.

This differential is the result of the way the Barnett formula has operated since the 1970s, including factors such as:

- A relatively generous baseline settlement;

- A slower growing Scottish population (which eases the ‘Barnett Squeeze’);

- Various oddities in terms of how the formula has worked in the past – including treatment of Non Domestic Rates and one-off spending increases.

Of course there are heated debates about the Barnett Formula, its merits, the role of oil, the underlying politics and inter-regional fairness across the UK.

But what we can conclude factually is that it is this mechanism that provides most of the uplift we see in spending in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK (not income tax decisions).

Concluding points

As ever in these sorts of debates, there are elements of truth in both sides.

It is the case that the Scottish income tax system is designed to raise additional revenues. Although, as we have explained, the way the changes have been designed the majority of individuals will pay fractionally (maximum 40p a week) less than in rUK, with more substantial increases for those earning more than £27,200.

It is also the case that devolved Scottish spending is much higher than equivalent spending in other parts of the UK. But this is not a consequence of the decision to issue higher tax bills to some people in Scotland, relative to what they would have paid in rUK.

Funding for commitments on tuition fees, childcare, free personal care, free prescriptions etc, stem yes, in part, from policy priorities in Scotland but also from the Barnett formula and the underlying distribution of public spending across the UK by successive UK governments. We’ll leave the politics of this for others to debate.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.