Hours worked play a significant role in determining earnings inequality among those in-work, and can influence the likelihood that working households find themselves in poverty. The security and regularity of hours also influence financial security and wellbeing.

Earlier in 2020, we embarked on a new project that looks at how hours of work influence inequality and poverty. The aims of the project are to examine trends in hours worked, the factors determining those trends, and how those trends are influencing poverty and inequality, and to use these findings to make recommendations for policy.

The work is made possible by the support of the Standard Life Foundation, and is being delivered by the Fraser of Allander Institute and the Scottish Centre for Employment Research.

Today we publish findings the project’s interim report. The interim report summarises the initial results of analysis of major UK wide surveys of the labour market and household incomes. The remainder of the project will involve further data analysis alongside qualitative research with employers and employees, and an analysis of trends in hours worked and policy responses in other countries.

Over the next few days we will summarise key points from the interim report in a series of short articles. Today’s blog looks at recent trends in hours worked by individuals and households, and the role these trends play in influencing inequality and poverty.

Hours worked account for a small but increasingly important part of male earnings inequality

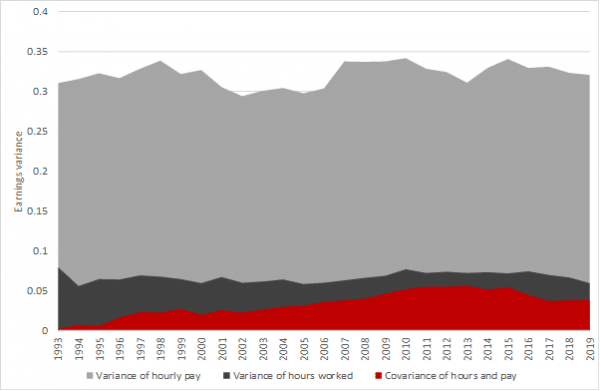

Inequality in weekly earnings can be accounted for through three channels: variance in hourly pay; variance in hours worked; and the correlation between hourly pay and hours worked (in other words, do high paid jobs tend to go hand-in-hand with relatively long hours, accentuating earnings inequality, or shorter hours, reducing inequality?)

For men, inequality in hourly pay accounts for the lion’s share of overall earnings inequality (the contribution of variance in hourly pay to the variance of weekly earnings is shown in light grey in Chart 1). Variance in hours worked (shown in dark grey) accounts for a relatively smaller share (most men continue to work something akin to a 40-hour week).

Chart 1: Changes in the pattern of hours and pay acted to increase earnings inequality among men

Decomposing the change in variance of log earnings, prime age males

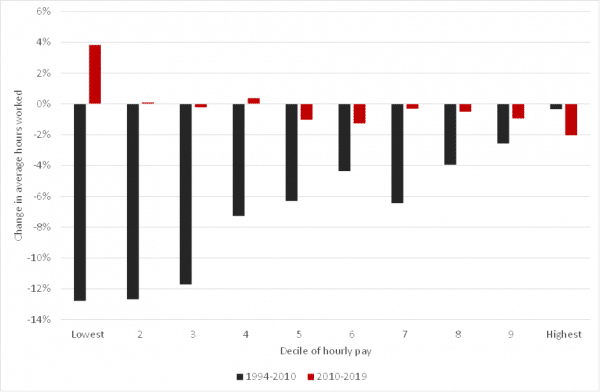

But something interesting happened in the period up to 2010: between the mid-1990s and 2010, hours worked by men in low paid jobs declined more rapidly than among men working in higher paid jobs (Chart 2).

For example, men in the lowest paid decile of jobs worked an average of 46 hours per week in 1994, but 39 hours in 2010; for men in the highest paid decile of jobs, average hours worked remained unchanged at 46 over the period. The strengthening correlation between hourly pay and hours worked contributed to rising male earnings inequality over the period – as shown by the red part of Chart 1.

Chart 2: Hours worked declined much more in low paid than higher paid jobs until 2010

Changes in hours worked by decile of hourly wage, prime age men

What might explain this trend? It cannot be explained by changes in demographic composition of the lowest paid – the trend is observed for men of all ages, not just the young or old. Nor can the trend be obviously explained by rising female employment in couple households – the trends are common to low-paid men across different family types (those living alone or in couples, and those with and without children).

Falling availability of overtime, which has affected middle and low paying jobs more than high-paying jobs, can account for some but not all of the trend. Falling overtime availability is likely largely to reflect employers’ attempts to control costs.

The increasing correlation between hours worked and pay ceased, and even reversed slightly, after 2010, with hours worked actually increasing slightly among low-paid men. This may reflect workers’ attempts to offset real terms declines in hourly pay, and possibly to signal commitment to employers during a period of heightened economic uncertainty.

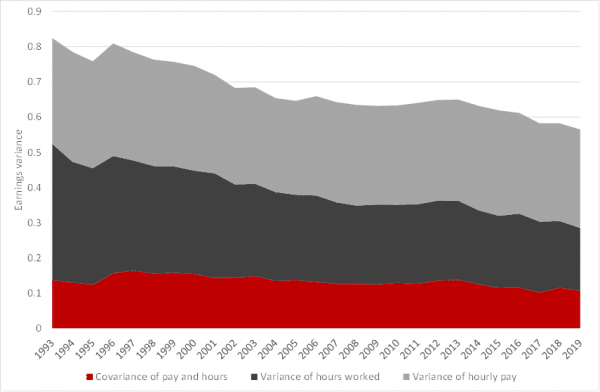

Hours worked account for a large but declining share of female earnings inequality

Hours worked play a more significant role in influencing earnings inequality amongst women. This is not because inequality in hourly pay is lower amongst women than amongst men. Instead, it reflects the fact that there is far greater variance in weekly hours worked amongst women compared to men.

There is a positive correlation between females’ hourly pay and hours worked (i.e. higher paid women tend to work longer hours than low-paid women). This relationship has declined very gradually in the past two decades, as average hours worked have increased slightly faster in low paid jobs relative to high paid jobs.

But most of the decline in female earnings inequality since the mid-1990s is accounted for by a fall in variance of hours worked. This reflects an increase in the average hours worked by part-time employees, a slight increase in the proportion of women working full time (Chart 3), and an increase in hours worked by women with children relative to those without.

Chart 3: Earnings inequality has fallen among women, driven by a narrowing of the dispersion of hours

Changes in hours worked by decile of hourly wage, prime age females

Households in in-work poverty are characterised by shorter working hours

There has recently been much policy discussion about in-work poverty, defined as the proportion of people living in households with net equivalised income below 60% of the mean where someone is in work.

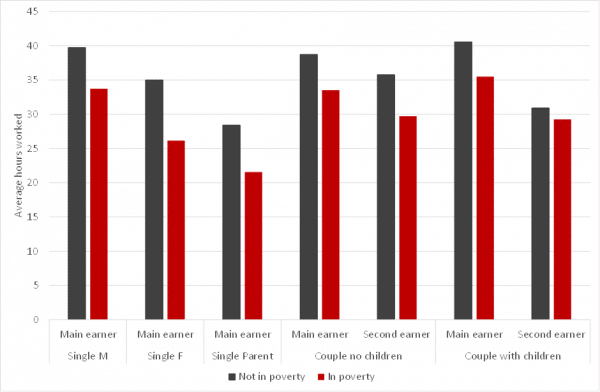

Why might working households be in poverty? Being employed in relatively low paying work is clearly one explanation, but hours worked matter too. The average weekly hours worked by the main earner in a working household in poverty is around 33, compared to 39 for households not in poverty. Second earners in working households also tend to work fewer hours than second earners not in poverty.

This trend for workers in households in poverty to work fewer hours on average than those not in poverty exists across all family types (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Working fewer hours is a feature of in-work poverty across all household types

Average hours worked by workers in and not in HHs in poverty, by household type

There are a couple of important points to take from Chart 4. The first is the point made already: workers in poverty tend to work fewer hours than those not in poverty, indicating that hours worked are, at least to an extent, a factor influencing the likelihood of being in poverty. But it is also striking that both main earners and second earners work only slightly fewer hours per week on average than their not-in-poverty counterparts. That tells us that there are factors other than hours worked influencing the likelihood of probability.

But working longer hours will often not, in itself, be enough to move out of poverty

We formalise the importance of hours worked in determining in-work poverty by modelling the probability of a working household being in poverty as a function of hours, hourly pay, and characteristics of the household.

The results imply that hours worked are a statistically significant factor in determining in-work poverty, but the size of the effect is relatively small. Working longer hours is no guarantee that a household will move out of poverty, particularly when facing some combination of low-pay, high marginal rates of earnings taxation or benefit withdrawal, and high housing costs.

In the next article we will consider the extent to which workers are satisfied or dissatisfied with their patterns of working hours.

Authors

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.

Mark Mitchell

Mark Mitchell is a former research associate at the FAI. In 2021, Mark moved to a post in the Competition and Markets Authority. His research area is applied labour economics, focussing on the causes and effects of human capital accumulation over the lifecourse.

Robert Stewart

Robert is a Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Scottish Centre for Employment Research