It has been widely publicised that the Scottish budget may face income tax ‘reconciliations’ totalling £1bn over the next few years. But what are these reconciliations and why do they come about? Do they tell us anything about Scotland’s economic performance, or do they just reflect forecast error?

What are these reconciliations?

Simply put, the Scottish budgets in 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20 were set on the basis of forecasts that – with hindsight – look to have been too optimistic.

Derek Mackay has no choice but to plan his budgets on the basis of the forecasts that are available to him at the time.

But with hindsight, it now looks like the budgets in 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20 were planned based on an assumption that more resources were available to the government than has subsequently turned out to be the case.

The reconciliations are simply an adjustment to address this ‘forecast error’.

What are the numbers we’re talking about?

Specifically, the latest forecasts imply the Scottish budget in 2017/18 had £229m less resource than was thought at the time, the 2018/19 budget had £608m fewer resources than was thought at the time, and the 2019/20 has £188m less than was thought when it was presented to parliament in December.

Does that mean there is a black hole in the Scottish budget?

It’s important to note that what is happening here is that there is a transfer of resources across budget years. If the ‘correct’ forecasts had been used for 2018/19, that budget would have been £608m smaller at the time. Instead, because the original forecasts now appear to have been too generous, the 2021/22 budget will be reduced by £608m to claw these monies back.

To call this a ‘black hole’ is an over-dramatization. But it does mean the Scottish Government will have to find resources from future budgets to pay for these reconciliations.

So the reconciliations come about because Scottish income tax revenues have not performed as well as had been forecast?

It’s not quite that simple unfortunately. There are two parts of the story.

The Scottish budget is, of course, dependent on Scottish income tax revenues. But what also matters is the income tax block grant adjustment (BGA). See here for a reminder about how the scheme works.

The BGA is an estimate of the revenues that the UK Government has foregone as a result of devolving income tax to Scotland. It is calculated by estimating how much revenue the UK Government would have collected from Scotland if UK tax policy still applied in Scotland, and if the Scottish tax base had grown at the same rate as in the rest of the UK.

The reconciliations have come about in part because Scottish income tax revenues have not grown as strongly as forecast. But a larger part of the reconciliations actually comes about because rUK income tax revenues have grown more quickly than originally forecast by the OBR.

The Scottish budget is exposed to both sets of forecast error.

What does all this tell us about the state of the Scottish economy?

In themselves, the reconciliations tell us nothing about the performance of the Scottish income tax base relative to the equivalent rUK income tax base.

For that, we need to look at the difference between the latest forecast for Scottish income tax revenues and the latest forecast for the income tax BGA. This difference is known as the ‘net tax’ position.

In principle, if Scotland had the same tax policy as the UK, and if the Scottish tax base (taxable income per capita) had grown at the same rate as in rUK since income tax was devolved, Scottish revenues should be the same as the BGA. The Scottish budget would be no better and no worse off than it would have been without income tax devolution.

And in principle, if Scotland sets a higher tax policy than rUK, then – if the Scottish tax base grows at the same rate as in rUK – Scottish revenues should be higher than the BGA, with the positive ‘net tax’ position reflecting the revenue effect of the Scottish tax policy.

So what is the ‘net tax’ position according to the latest forecasts?

According to the latest forecasts, the Scottish revenues will be smaller than the BGA by around £122m in 2017/18 (a ‘net tax’ position of -£122m); smaller by around £179m in 2018/19, and smaller (by £5m) in 2019/20.

Implicitly, this means that rUK income tax revenues per capita are growing faster than Scottish income tax revenues per capita, despite income tax rate increases in Scotland.

How does this link back to the reconciliation issue?

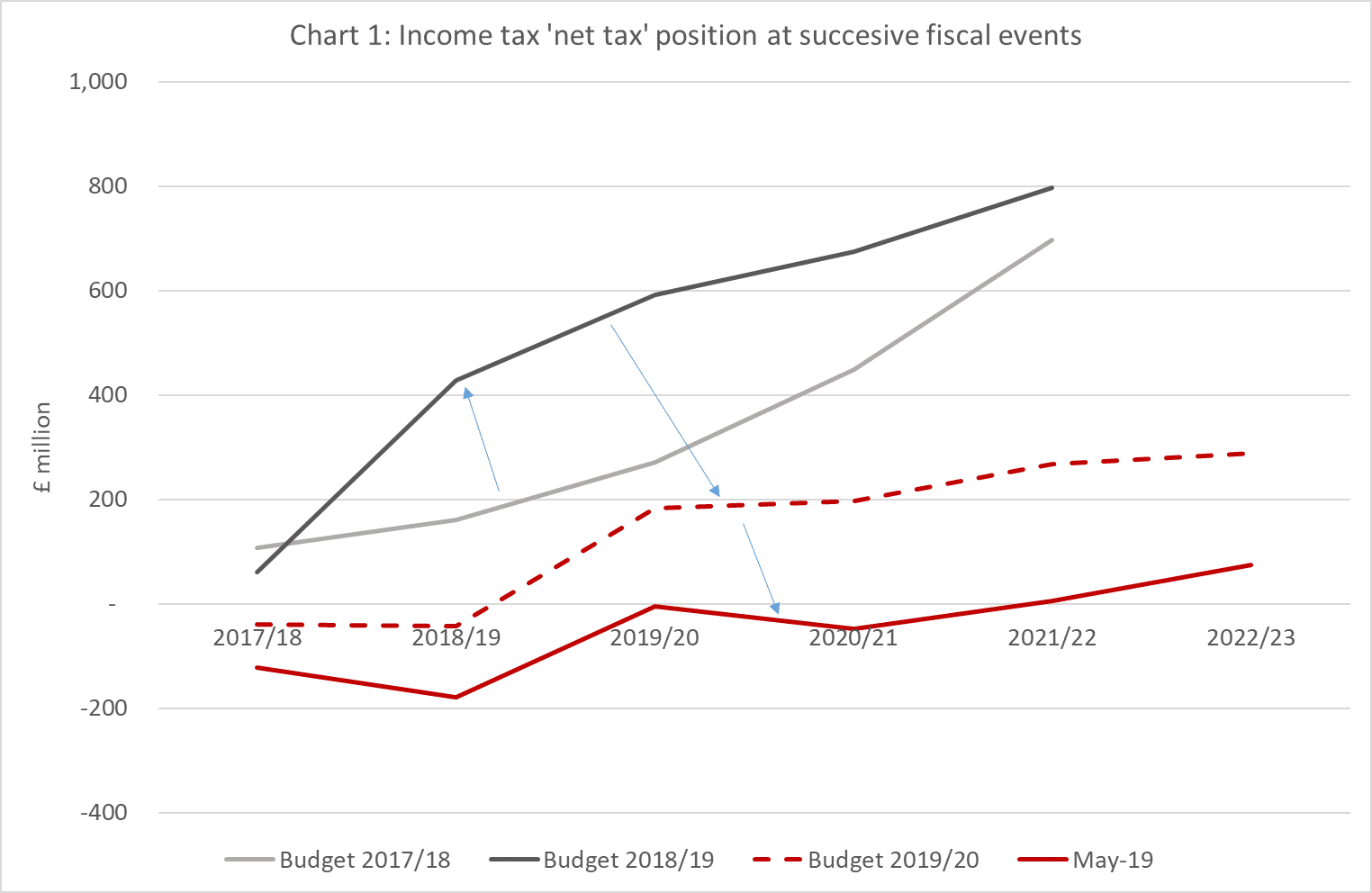

As Chart 1 shows, the forecasts made at the time of the 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20 budgets did not foresee the full extent of this differential performance – hence the reconciliations.

(The Chart shows the ‘net tax’ position at successive fiscal events. When the 2017/18 budget was published, the net tax position was forecast to be positive in Scotland’s favour. By the time of the 2018/19 budget, the net tax position had moved more strongly in Scotland’s favour, reflecting the effects of the Scottish income tax policy, and an expectation that Scottish earnings growth would match rUK earnings growth. But by the time of the 2019/20 budget the net tax position had deteriorated, reflecting downward revisions to the forecast of Scottish earnings growth and upward revisions to the forecast of rUK earnings growth. The latest forecasts indicate a further worsening of the position.)

But I thought the Scottish Government had chosen to set a policy that sought to raise more revenue in Scotland than UK Government policy?

Yes, in 2019/20, Scottish taxpayers are paying some £500m more in income tax than they would pay under the UK policy.

But the revenue effects of the Scottish tax policy have been completely offset by relatively weaker performance in the Scottish tax base.

Is it perverse that the Scottish budget should face reconciliations when the Scottish economy is performing well?

Some have questioned whether it is ‘perverse’ for the Scottish budget to face downward reconciliations when many headline indicators – the employment rate for example – are relatively positive.

This is a misunderstanding of how forecast error comes about, and how the fiscal framework works.

Scottish budgets are set based on a set of forecasts for Scottish revenues and forecasts for the BGA. Since those forecasts were made, Scottish revenues have not performed quite as well as anticipated, and rUK revenues have performed better than anticipated, resulting in a higher BGA than forecast.

This is not perverse, it’s how the fiscal framework was designed to work and what the Scottish Government signed up to. In effect, if the Government spent more money than it actually raised, it needs to hand it back in the future.

Did we know about these risks?

Yes.

There is an argument that the Government’s borrowing powers could be extended to allow it to borrow more than it currently can to manage the timing of how it responds to these reconciliations.

But remember the reconciliations are only a timing issue.

The risk that Scotland’s tax base performs less well than the equivalent tax base in the rest of the UK was a risk that the government signed up to in 2016.

Summary

The latest forecasts indicate that earnings in Scotland have grown less strongly than they have in the rUK since income tax was devolved.

As a result, income tax revenues per capita in Scotland are barely managing to grow at the same rate as in rUK – despite successive increases in Scottish income tax policy.

Weaker growth in the Scottish tax base relative to the rUK tax base has effectively wiped out any dividend of higher revenues in Scotland from increased tax rates.

If this position had been forecast when budgets were set, there would be no need for reconciliation – the position would have been baked-in from the outset.

Because this was not foreseen, the Scottish Government faces tricky ‘reconciliations’ in the short-term. A more medium to longer-term concern will be whether or not such a trend in tax performance continues.

Such debates may appear to be a largely technical issue but they pose some challenging questions about Scotland’s future public finances and emerging risks. It’s not clear that these debates have been given the consideration that they deserve.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.