Today we published our latest Economic Commentary.

In this blog, we summarise some of the key points from our latest outlook.

We also publish a series of articles from guest contributors.

- Measuring Scotland’s economic performance

- Productivity Trends in Scotland

- The financial performance of Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) hub schemes

- Too big to be local, too small to be strategic

1. The decision to extend the deadline for the UK’s withdrawal from the EU has provided some temporary respite from recent heightened economic uncertainty, but only for a short while with the range of scenarios as wide as ever.

In our central forecast, we continue to assume that the UK makes an orderly departure from the EU at some point in 2019. Although we also assume that uncertainty continues to impact on investment and private sector spending decisions for the foreseeable future.

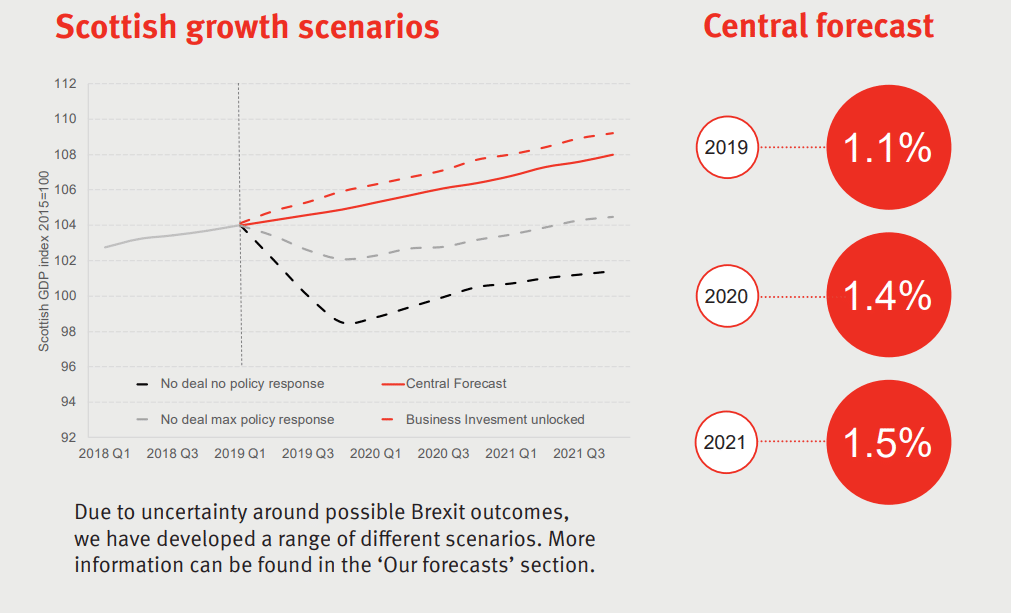

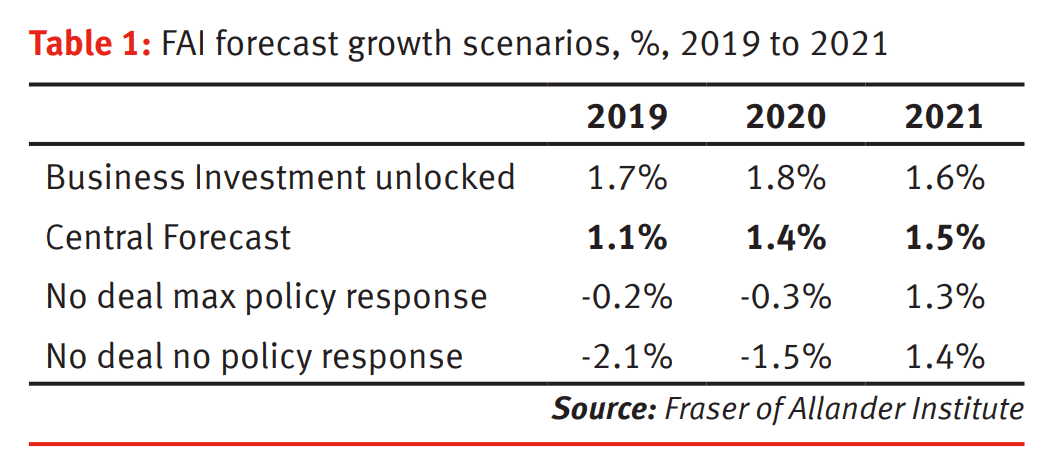

In light of weaker recent data, and the decision to grant an extension to October 31st, we have lowered our forecast a little to 1.1% for 2019 and 1.4% and 1.5% for 2020 and 2021 respectively.

To illustrate the range of possible options, alongside our central forecast, we have produced a number of scenarios for how the economy might evolve, depending upon the outcome of the ongoing political process to agree the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

- In the worst case scenario, there is a significant contraction in the Scottish economy (with a peak to trough of 5.5%, leading to growth in 2019 of -2.1%);

- However, this assumes no policy response from the Government or the Bank of England, which is not realistic. With a policy response, output still contracts, but by much less (a peak to trough contraction of 1.9%, leading to growth in 2019 of -0.2%).

- There is also a more positive scenario where uncertainty is reduced and confidence returns, perhaps if a deal is agreed. In this case, we think that growth could surprise on the upside, with growth of 1.7% in 2019.

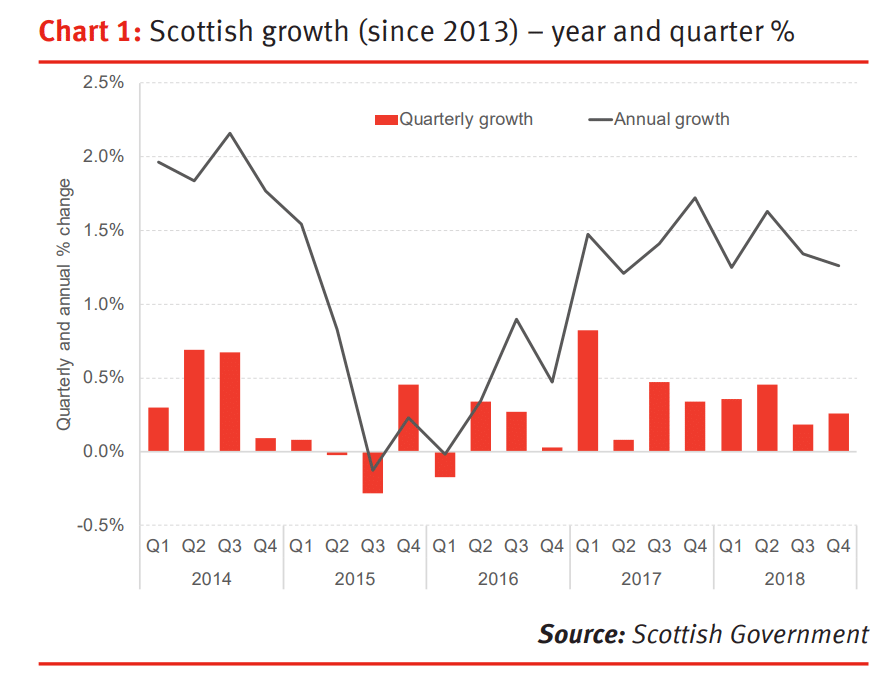

2. The Growth in the Scottish economy was steady – if unspectacular – in 2018. This was in line with our own forecast, where our modelling in late 2017 suggested growth of 1.4% in 2018.

This weak growth was mirrored across the UK.

Indeed, new FAI nowcast modelling estimates that Scotland was the fastest growing part of the UK outside of London in 2018.

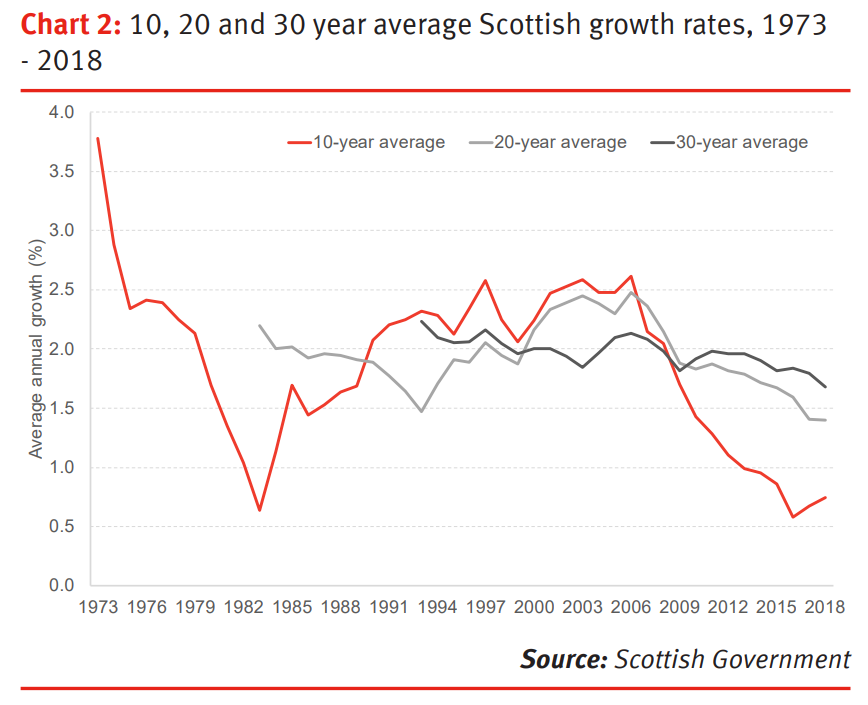

3. Of significant concern however, is the sustained decline in Scotland’s long-term average growth rate. It’s clear therefore that not all of Scotland’s weak growth performance can be pinned on Brexit.

These figures should provide a wake-up call to policymakers in both Scotland and the UK, but we fear that the sustainable growth question in Scotland is one that is continually pushed to the back burner.

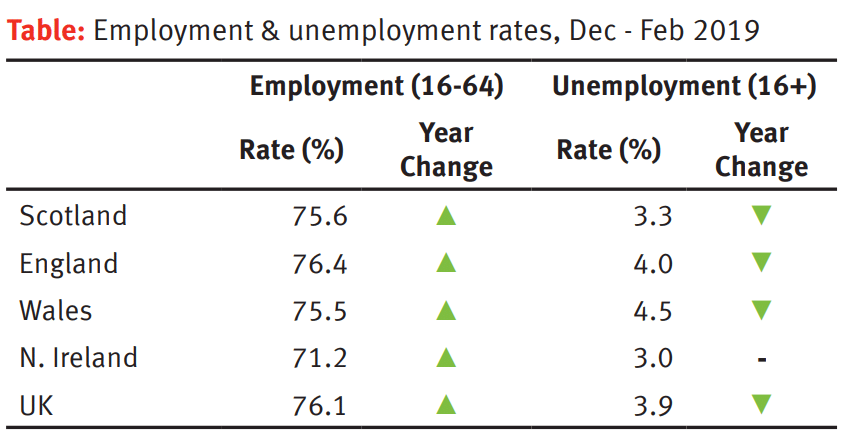

4. One bright spot in the Scottish economy remains the performance of the labour market.

Scotland’s headline labour market indicators have arguably never looked better. The unemployment rate at 3.3% is now at its lowest rate since 1992, and the employment rate at 75.6% is near its record high of 75.8%.

That said, wage growth remains relatively weak, with many workers seeing little or no wage growth.

Ordinarily with headline labour market numbers this impressive, we’d expect to see much more rapid wage growth. More generally concerns remain about the quality of work available and how fragile the experience of work is for some.

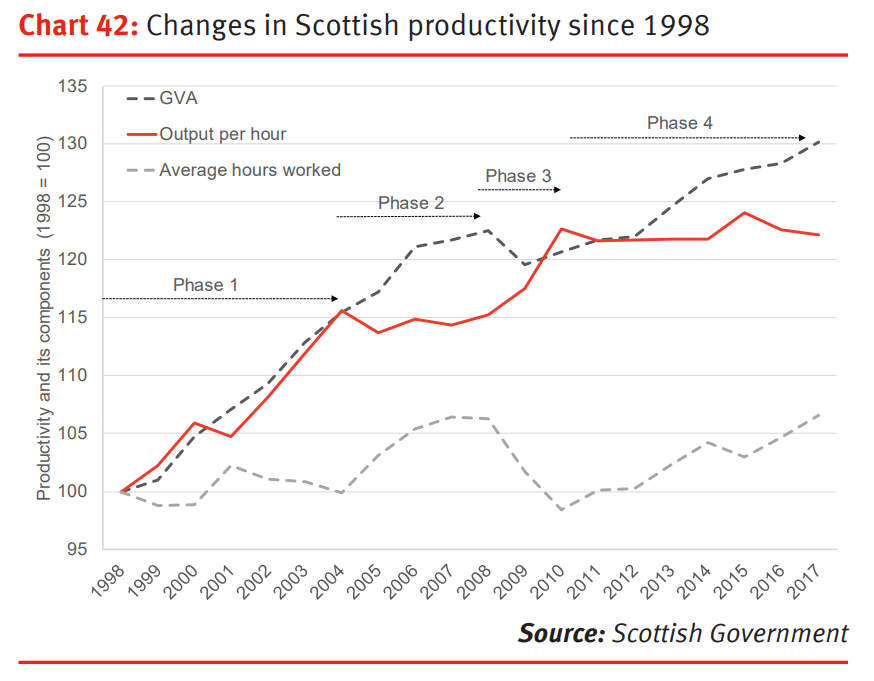

5. Of course, one consequence of strong labour market outcomes and weak growth is that productivity takes a hit.

Levels of productivity in Scotland are no better than they were in 2010. And whilst, Scotland has ‘caught-up’ with the rest of the UK in recent years, this is largely due to a relative fallback in the amount of hours we are working. As a result, on wider measures of economic prosperity – such as household income per head – we have slipped back in recent years relative to the UK.

6. Productivity is of course crucial for supporting real wage growth in the long-run

As a result, whilst the strong labour market figures are to be welcome, you don’t have to look far to see the negative consequences of poor wage growth. New figures published last month showed that 60% of working-age adults in Scotland in relative poverty (after housing costs) were living in working households, up 12%-points on two decades ago.

And for all the talk about inclusive growth, nearly 1 in 4 children in Scotland live in poverty.

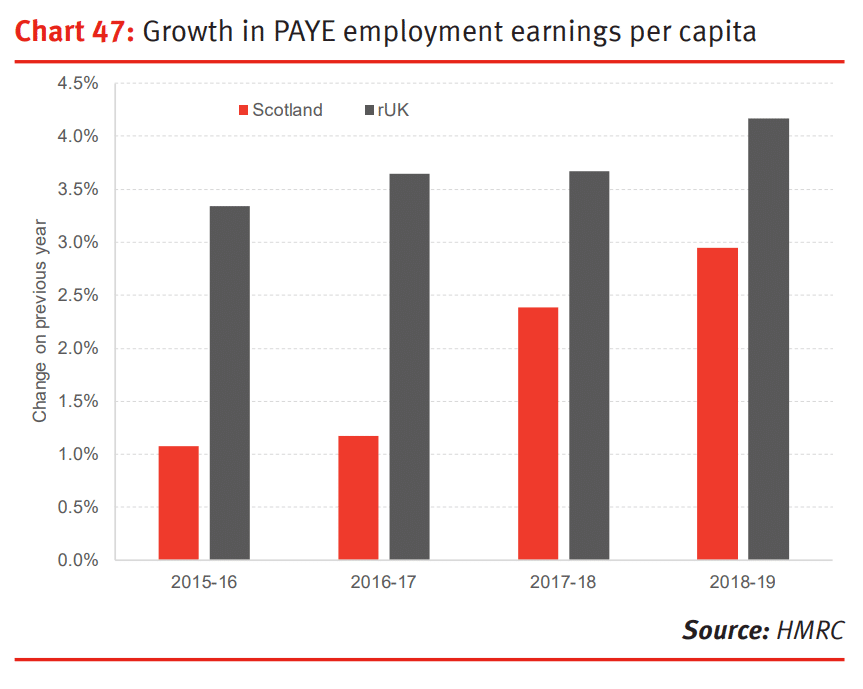

As we pointed out in a blog earlier this year, employment income per head in Scotland seems to have been lagging behind the UK as a whole in recent years.

This is likely to have significant implications for the Scottish Budget. Firstly, the amount being raised this year from higher income taxes in Scotland is much less than previously thought. The increase in tax rates for some is being eroded by weaker growth in the tax base.

Secondly, it is likely that the Scottish Government may be forced to pay-back hundreds of millions of pounds spent over the last couple of years if the initial forecasts used to determine these amounts do indeed turn out to be over optimistic.

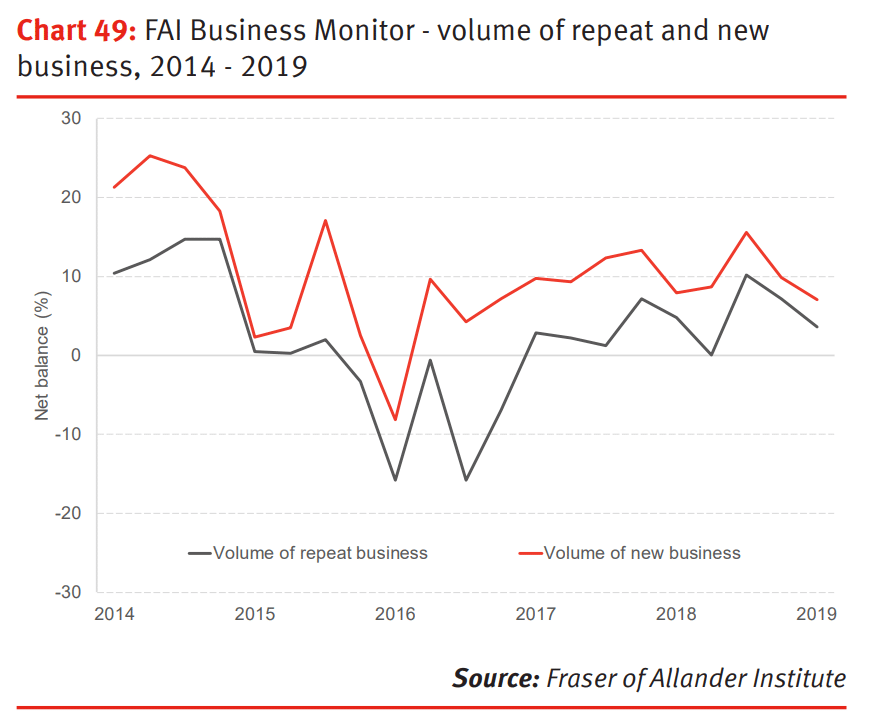

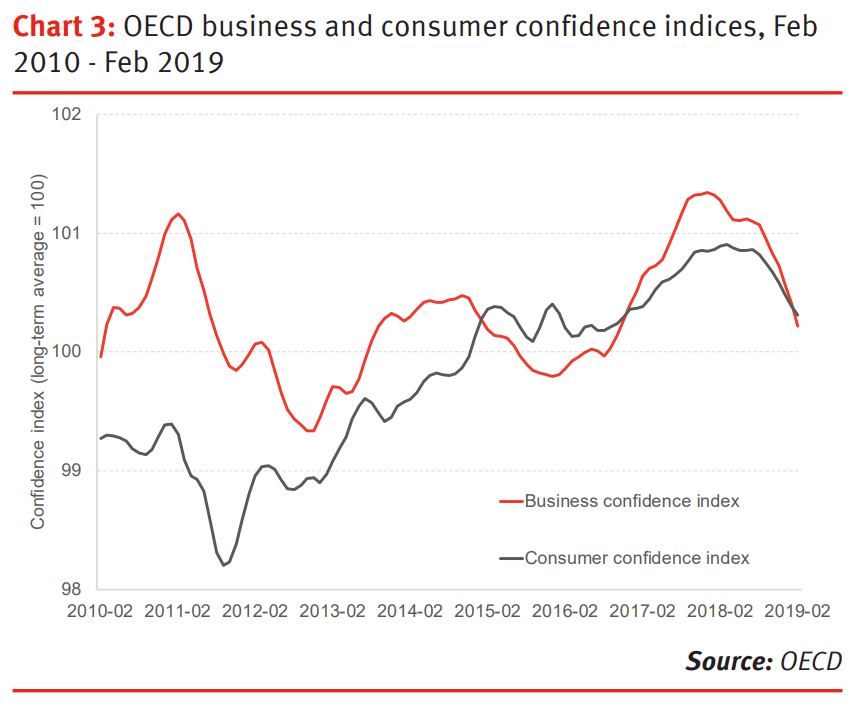

7. The immediate outlook remains uncertain. Most surveys point to growth continuing but many businesses remain nervous about what might happen next and are therefore postponing investment

For example, our own Scottish Business Monitor suggests that the volume of business activity in the Scottish economy has continued to grow during the first three months of 2019, although investment intentions remain negative (with a net balance of -7%).

8. At the same time, the global outlook looks more uncertain than when we published our last commentary at the end of 2018.

There are a number of reasons for this –

- Overall sentiment indicators across advanced and emerging economies have weakened since the autumn, suggesting fading momentum in global growth.

- Italy has re-entered recession, whilst Germany narrowly avoided following suit. Chart 4.

- The significant fiscal stimulus injected into the US economy by President Trump’s tax cuts has started to wear off.

- Uncertainties over the longer-term health of emerging markets – most notably whether or not China’s years of rapid growth are coming to an end – have injected a new wave of volatility into the outlook and financial markets.

- Finally, the ongoing threat of trade skirmishes between the US and China has weakened forecasts.

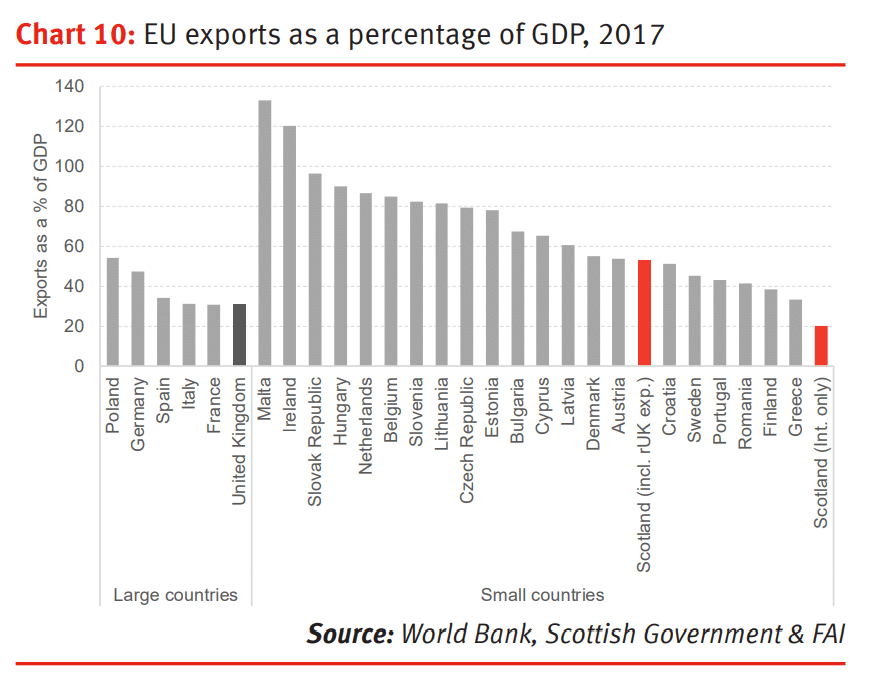

9. It is against this backdrop that the Scottish Government will publish a new Export Action Plan next month

Scotland has significant export strengths in a number of markets. But there is scope for improvement.

As a share of our economy, Scotland exports less than many comparable countries within the EU. Including UK exports, Scotland has a ratio of exports to GDP of around 53%. But this falls to 20% when looking only at international exports. This compares to EU and OECD averages of 45% and 28% respectively.

Our export base is too narrow. It depends upon a relatively small number of firms, operating in a small number of sectors, selling into a small number of markets.

With limited resources the Scottish Government will need to develop a robust evidence based approach that moves beyond previous strategies which replied upon high level targets and opaque ambitions of ‘internationalisation’.

Tough decisions will be required on what businesses to offer support to – e.g. is the focus upon a small number of firms already exporting, or the large volume of smaller firms who do not currently export?

What sectors should policy help support? And what markets should be targeted?

What practical steps should be taken, and how should different initiatives be evaluated?

10. How we boost exports – whatever the outcome of the Brexit process – is just one of the key policy questions that needs attention.

The sustainable growth challenge is arguably still something that remains inadequately addressed in the political discourse in Scotland.

In a follow-up blog, we’ll discuss these issues in more depth (see also our policy section of the commentary)

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.