It seems a near certainty that the Scottish Government will seek to increase income tax revenues in tomorrow’s budget – through a combination of changes to rates and thresholds. If this happens, it will kick-off a hotly contested debate about the impact on the Scottish economy.

The Scottish Chambers of Commerce have got their response in early, arguing that “at a time of sluggish growth and faltering business investment, a competitive Scotland cannot afford to be associated with higher taxes than elsewhere in the UK”. The Federation of Small Businesses has also warned about the impact of tax increases on the economy.

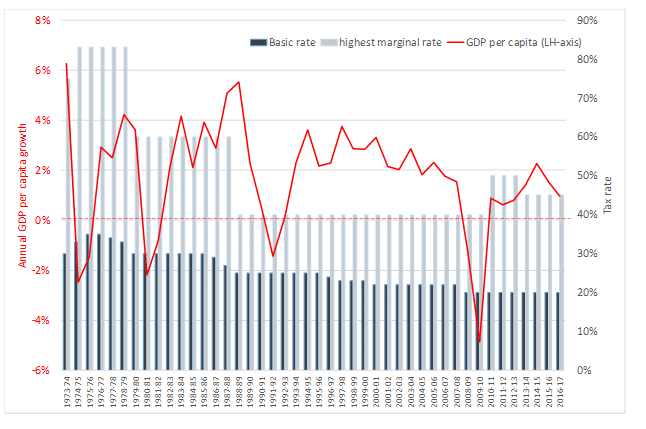

A glance at cross-country comparisons, reveals that there isn’t an obvious correlation between how much tax is raised in a country (as a percentage of GDP) and the long-run rate of economic growth. And a quick look at UK income taxes and growth rates doesn’t reveal any clear results either.

Basic rate of income tax, top marginal rate of income tax, and growth of GDP per capita, UK, 1973/74 – 2016/17

But what does the evidence say about whether an increase in income tax will weaken economic growth?

A fiscal stimulus with a balanced budget

There have been a number of people – and political parties – calling for the Scottish Government to increase public spending to ‘protect’ public services.

Of course it’s important to remember that under the new fiscal framework, the only way that the Scottish Government can increase day-to-day spending – over and above the block grant – is to increase taxes. Unlike the UK Government, they cannot fund additional day-to-day spending through borrowing (although they can fund some additional capital spending through borrowing).

The extent to which any decision to increase spending by raising taxes like-for-like will have a positive or negative impact on the economy depends upon three key factors:

- The short-run multiplier impacts of a (balanced budget) increase in government spending;

- The impact on incentives for income tax payers;

- The actual and perceived impact on Scotland’s long-term economic competiveness.

The multiplier impacts of government spending

Increasing income tax will reduce the take home pay for those whose tax liability increases. This will cut private spending in the economy. But on the other hand, the government will now be in a position to spend more money. This will, in turn, boost demand.

Effectively spending power has switched from households to government.

Whether the net impact turns out to be positive or negative at the margin, will depend upon whether or not the ‘multiplier’ impacts from the reduced household spending are greater or smaller than the equivalent ‘multiplier’ impacts from the higher government spending.

In the end, the differences in multiplier effects discussed here are likely to be relatively marginal, particularly given the scale of tax change being considered. To put it in context, a tax rise of £300m is equivalent to just 0.2% of the Scottish economy.

The impact of higher tax rates on individual incentives

Another avenue it could have an impact is on incentives.

Higher marginal rates of income tax may encourage some individuals to work less. Some could retire early (or take semi-retirement), others might decide to work fewer hours, freelancers and the self-employed might take on fewer commissions.

But of course, other employment opportunities may be created from any increase in the public sector workforce.

It’s also important to make a distinction between the responsiveness of economic activity to a tax change vs. the responsiveness of taxable income. Higher tax rates can induce some individuals to report lower taxable income, but this in itself doesn’t mean that economic activity has fallen. Instead, much of the responsiveness of income to tax changes reflects individuals greater propensity to avoid paying tax, rather than to ‘doing less’.

In other words, a higher rate of tax might result in people avoiding tax by – legally – making a larger contribution to a pension or taking more income in the form of dividends rather than wages (remember Holyrood only has responsibility for non-savings non-dividends income tax). Of course at the margin, lower revenues means less government spending in the economy.

The impact on competitiveness and attractiveness of the Scottish economy

There are other less well defined, but still important, avenues through which changing income taxes could have an impact on growth. Particularly over the long-term.

At the heart of this, is the issue of whether or not Scotland is – and is perceived to be – just as competitive a place to do business as it was prior to the tax increase.

Scottish based firms may feel they have to offer higher wages to compensate employees. This may have knock-on implications for investment in plant & machinery, research & development and in training & development should firms seek savings elsewhere. Similar considerations will be made by outside investors as they compare Scotland to other locations.

On the other hand, if the government uses the additional revenues to invest more in skills and education, childcare, infrastructure etc. then this may help to boost the overall competiveness of the economy.

But there is no guarantee that such investments will lead to the better outcomes that the government intends. Even if they did, they will take time to materialise.

Either way, the magnitudes of sums being discussed are not that significant to radically change behaviour or unleash a spending bonanza.

A key element though, like it or not, is perception amongst the business community both here and outside Scotland.

It is vital that the government has in place a strong strategy to make the case that Scotland is an (even more) attractive place for investment and growth.

Final thoughts

The avenues through which changes in income tax could have an impact on the economy are relatively well understood. What is less clear is the relative magnitude of these impacts and which effects (positive or negative) will dominate.

Whatever decision is taken, the government will be under pressure to put forward a convincing case about their wider actions to support Scotland’s economy in a world where income taxes – for some – will be higher than elsewhere in the UK.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.